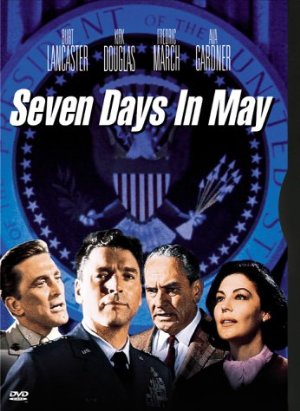

Seven Days in May (1964)

May 4, 2016 6:38 PM - Subscribe

United States military leaders plot to overthrow the President because he supports a nuclear disarmament treaty and they fear a Soviet sneak attack.

NYTimes: Essentially, the film offers a gripping melodramatic account of the steps taken by the President when he is advised of a secret suspicion that the top Air Force general, who is chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is heading a plot to take over the Government on a certain Sunday in May. This general, a highly popular hero, is moved to this traitorous enterprise because he fears the consequences of a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Russians that the President has negotiated.

Leads on this mammoth maneuver are swiftly and smartly pursued in the best spy-fiction tradition, amazing discoveries are made and a climactic confrontation between the Presidnt and his adversary is reached. But the interesting thing is that the import of the drama here takes a marked turn into a delicate, critical area of political philosophy.

In some vivid and trenchant dialogue, which Rod Serling has composed in doing the screenplay from the novel, the President sadly notes the cause of such a move toward upheaval is not one man's lust for power but the consequence of a concentration of fear and anxiety. The enemy is not the general, he says, it is the nuclear age. "It happens to have killed man's faith in his ability to influence what happens to him," he says.

If for no more than this statement, the film is worth its salt.

But there is a whole lot more in it. The whole thing achieves a tingling speed and irresistible tension under John Frankenheimer's direction, which deftly lifts some of the tricks of pictorial and musical emphasis from the old Nazi "Blitzkrieg" films. It gathers a sense of actuality and plausibility (except for one twist; that is the supposition of a giant secret military base).

And it is expertly played.

Fredric March's performance as the President is the firmest and the best. In it is reflected an awareness of the immensity of the anguish of this man. Kirk Douglas is sturdy and valiant as the Air Force colonel who smells out the plot, and Burt Lancaster is impressively forceful as the engineer of the coup d'état.

Martin Balsam as the President's press secretary, Edmond O'Brien as a doughty Senator, Ava Gardner as a Washington hostess and Whit Bissell as a Senatorial sneak are among the several excellent performers of secondary roles.

As dismal as is the complication that they and this picture present, the acknowledgment of its possibility and the discovery of how it might be resolved, with wisdom and fundamental courage, make this a brave and forceful film.

Trailer

NYTimes: Essentially, the film offers a gripping melodramatic account of the steps taken by the President when he is advised of a secret suspicion that the top Air Force general, who is chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is heading a plot to take over the Government on a certain Sunday in May. This general, a highly popular hero, is moved to this traitorous enterprise because he fears the consequences of a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Russians that the President has negotiated.

Leads on this mammoth maneuver are swiftly and smartly pursued in the best spy-fiction tradition, amazing discoveries are made and a climactic confrontation between the Presidnt and his adversary is reached. But the interesting thing is that the import of the drama here takes a marked turn into a delicate, critical area of political philosophy.

In some vivid and trenchant dialogue, which Rod Serling has composed in doing the screenplay from the novel, the President sadly notes the cause of such a move toward upheaval is not one man's lust for power but the consequence of a concentration of fear and anxiety. The enemy is not the general, he says, it is the nuclear age. "It happens to have killed man's faith in his ability to influence what happens to him," he says.

If for no more than this statement, the film is worth its salt.

But there is a whole lot more in it. The whole thing achieves a tingling speed and irresistible tension under John Frankenheimer's direction, which deftly lifts some of the tricks of pictorial and musical emphasis from the old Nazi "Blitzkrieg" films. It gathers a sense of actuality and plausibility (except for one twist; that is the supposition of a giant secret military base).

And it is expertly played.

Fredric March's performance as the President is the firmest and the best. In it is reflected an awareness of the immensity of the anguish of this man. Kirk Douglas is sturdy and valiant as the Air Force colonel who smells out the plot, and Burt Lancaster is impressively forceful as the engineer of the coup d'état.

Martin Balsam as the President's press secretary, Edmond O'Brien as a doughty Senator, Ava Gardner as a Washington hostess and Whit Bissell as a Senatorial sneak are among the several excellent performers of secondary roles.

As dismal as is the complication that they and this picture present, the acknowledgment of its possibility and the discovery of how it might be resolved, with wisdom and fundamental courage, make this a brave and forceful film.

Trailer

Douglas made some really smart choices in his performance - his character is not dumb, but he has a code and a perspective that he lives by and so you can see the disruptions to his well-ordered life and that code stack up and make him question the disruptions in what should be. He's not introspective at all, but he's aware, alert, and knows when something isn't right.

There's a moment where one character sums up Douglas' decision to bring this potential plot to the President even though he disagrees with the President about the treaty as essentially because "You believe in the constitution" and the look on Douglas' face is perfect: at once abashed and wondering, and Douglas is suddenly comfortable in this position of what could construed as betraying the Boss he otherwise admires and contributing towards a treaty he thinks is dangerous.

And the movie's got tones of that 1950s/60 style of melodrama (expressed mostly in philosophical terms) overlaying the drama that I think makes it feel less dated than it might otherwise seem.

posted by julen at 8:54 PM on May 4, 2016 [1 favorite]

There's a moment where one character sums up Douglas' decision to bring this potential plot to the President even though he disagrees with the President about the treaty as essentially because "You believe in the constitution" and the look on Douglas' face is perfect: at once abashed and wondering, and Douglas is suddenly comfortable in this position of what could construed as betraying the Boss he otherwise admires and contributing towards a treaty he thinks is dangerous.

And the movie's got tones of that 1950s/60 style of melodrama (expressed mostly in philosophical terms) overlaying the drama that I think makes it feel less dated than it might otherwise seem.

posted by julen at 8:54 PM on May 4, 2016 [1 favorite]

What's scary is to read about some of the gung-ho generals of those days. The fact that some of them seriously discussed making it look like Cuba had shot down an airliner to provide justification to attack, and the public griping about JFK, makes you realize that this story was more plausible than you might think.

posted by pmurray63 at 9:43 PM on May 4, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by pmurray63 at 9:43 PM on May 4, 2016 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Chrysostom at 8:25 PM on May 4, 2016