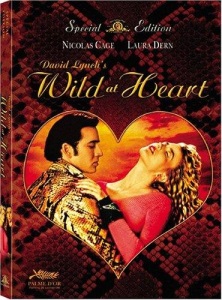

Wild at Heart (1990)

February 14, 2018 6:57 PM - Subscribe

Young lovers Sailor and Lula run from the variety of weirdos that Lula's mom has hired to kill Sailor.

Rolling Stone: Imagine The Wizard Of Oz with an oversexed witch, gun-toting Munchkins and love ballads from Elvis Presley, and you'll get some idea of this erotic hellzapoppin from writer-director David Lynch. Lynch's kinky fairy tale is a triumph of startling images and comic invention.

The Guardian: The story is told with an almost cartoon-like ferocity and a virtuoso appreciation of how to make the ordinary seem strange and the strange seem unutterable. Lynch's camera plunges through sequences as if hell-bent on showing you something you've never seen before.

Slant: And yet: There’s a sense in which Wild at Heart is more a film on the cusp, for in it we see Lynch testing the waters, poking here and there, making his way toward the farther-out worlds of Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire. Already in Wild at Heart we have characters who seem to be aware of being characters, of having their destiny guided by forces from without as well as within, tools in a narrative.

Entertainment Weekly: Wild at Heart is the first Lynch movie that could be accused of wearing its weirdness on its sleeve. From the joltingly ugly opening sequence, in which rebel without a cause Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) defeats an attacker by smashing the guy’s head against a marble floor until his squishy red brains are dripping out the back, you can feel Lynch trying to unsettle you — and, with equal calculation, chortling at his own bad-boy games.

Lynch, along with Martin Scorsese, is the most exciting filmmaker of his generation. Yet coming off that sensationally demented TV soaper Twin Peaks, he seems torn between making a mod genre picture — a scabrous and bloody Southern Gothic road comedy — and playing avant-garde show-off. The result is a sluggish, pretentious mess.

WaPo: It's not that Lynch has gone too far -- he went just as far in "Blue Velvet" -- it's that he's gone wrong. There are flashes of virtuosity in "Wild at Heart," but too much of what he's created here verges on self-parody. It's as if, for the first time, Lynch were trying to make a David Lynch movie. He's trying to top himself, and as a result, the picture feels more like the work of a Lynch imitator than the genuine item. It's like one of those episodes of "Twin Peaks" that Lynch didn't direct -- the ones that had everything except the master's transforming touch.

Roger Ebert: There is something repulsive and manipulative about it, and even its best scenes have the flavor of a kid in the school yard, trying to show you pictures you don't feel like looking at.

The movie is lurid melodrama, soap opera, exploitation, put-on and self-satire. It deals in several scenes of particularly offensive violence, and tries to excuse them by juvenile humor: It's all a joke, you see, and so if the violence offends you, you didn't get the joke.

NYTimes: It's the old fun-house principle. Nightmares are made real. Without moving, one seems to plummet through pitch darkness. The response in a fun house is a pleasurably scary physical sensation. The Lynch films go several steps further: nothing in life is fixed. All reality is relative.

The Dissolve: The biggest problem with Wild At Heart is that it isn’t always as liberated as it seems, especially in Lynch’s decision to saddle the entire film with a Wizard Of Oz allegory that occasionally connects, but more often seems like a square peg jammed into a round hole. Having visual cues like Marietta as a crystal-ball-wielding Wicked Witch Of The West is one thing, but Lynch clogging up the dialogue with Sailor talking about Jingle Dell needing some advice from the Wizard, or Big Tuna being “not exactly the Emerald City” is a little much even before Laura Palmer turns up as the Glinda The Good Witch. Road movies don’t have to follow the yellow brick road—that’s central to their appeal. They can wander.

PopMatters: But despite the violence and sociopathic behavior on display, this is also one of Lynch’s most humane, upbeat films -- if a film with a dog running off with a freshly severed hand in its mouth can be said to be upbeat. Sailor and Lula’s road trip is a deeply romantic fantasy diverted only temporarily by flying monkey interlopers, and their battered faith in their love and mutual goodness is rewarded in the end. Justice is meted out to most, if not all, of the evildoers, and the credits roll over a version of “Love Me Tender.” Compared to Lynch's bleak take on fate and human nature in, say, Eraserhead or Lost Highway, this is sunshine and sailboats.

The Film Stage: In turn, Wild at Heart finds itself primarily concerned with the construction of personal mythologies, perhaps the chief example being Sailor and his trademark snakeskin jacket, its donning in spaces both private and public accompanied by a monologue about how it represents his belief in individuality and personal freedom. (Even Lula chidingly mentions that she’s heard this about a million times already.) Of course, integral to these personal mythologies is the act of storytelling: Sailor and Lula provide backstory upon backstory about their troubled pasts that all naturally explain why these two damaged outcasts are perfect for each other. The film’s editing patterns make images from their stories (flaming homes, crying faces) bleed in and out when nobody is making so much as the slightest reference to them, giving the overriding feeling that their future will likely end up the same as their past.

Trailer

1990 was a big year for David Lynch

The craziest, most WTF moments in Wild at Heart

The David Lynch Retrospective: ‘Wild At Heart’

‘Wild at Heart’: A Twisted, Romantic Road Movie as a Lynchian Homage to ‘The Wizard of Oz’

The Tao of Nicolas Cage: Wild at Heart

Art of the Title

Rolling Stone: Imagine The Wizard Of Oz with an oversexed witch, gun-toting Munchkins and love ballads from Elvis Presley, and you'll get some idea of this erotic hellzapoppin from writer-director David Lynch. Lynch's kinky fairy tale is a triumph of startling images and comic invention.

The Guardian: The story is told with an almost cartoon-like ferocity and a virtuoso appreciation of how to make the ordinary seem strange and the strange seem unutterable. Lynch's camera plunges through sequences as if hell-bent on showing you something you've never seen before.

Slant: And yet: There’s a sense in which Wild at Heart is more a film on the cusp, for in it we see Lynch testing the waters, poking here and there, making his way toward the farther-out worlds of Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire. Already in Wild at Heart we have characters who seem to be aware of being characters, of having their destiny guided by forces from without as well as within, tools in a narrative.

Entertainment Weekly: Wild at Heart is the first Lynch movie that could be accused of wearing its weirdness on its sleeve. From the joltingly ugly opening sequence, in which rebel without a cause Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) defeats an attacker by smashing the guy’s head against a marble floor until his squishy red brains are dripping out the back, you can feel Lynch trying to unsettle you — and, with equal calculation, chortling at his own bad-boy games.

Lynch, along with Martin Scorsese, is the most exciting filmmaker of his generation. Yet coming off that sensationally demented TV soaper Twin Peaks, he seems torn between making a mod genre picture — a scabrous and bloody Southern Gothic road comedy — and playing avant-garde show-off. The result is a sluggish, pretentious mess.

WaPo: It's not that Lynch has gone too far -- he went just as far in "Blue Velvet" -- it's that he's gone wrong. There are flashes of virtuosity in "Wild at Heart," but too much of what he's created here verges on self-parody. It's as if, for the first time, Lynch were trying to make a David Lynch movie. He's trying to top himself, and as a result, the picture feels more like the work of a Lynch imitator than the genuine item. It's like one of those episodes of "Twin Peaks" that Lynch didn't direct -- the ones that had everything except the master's transforming touch.

Roger Ebert: There is something repulsive and manipulative about it, and even its best scenes have the flavor of a kid in the school yard, trying to show you pictures you don't feel like looking at.

The movie is lurid melodrama, soap opera, exploitation, put-on and self-satire. It deals in several scenes of particularly offensive violence, and tries to excuse them by juvenile humor: It's all a joke, you see, and so if the violence offends you, you didn't get the joke.

NYTimes: It's the old fun-house principle. Nightmares are made real. Without moving, one seems to plummet through pitch darkness. The response in a fun house is a pleasurably scary physical sensation. The Lynch films go several steps further: nothing in life is fixed. All reality is relative.

The Dissolve: The biggest problem with Wild At Heart is that it isn’t always as liberated as it seems, especially in Lynch’s decision to saddle the entire film with a Wizard Of Oz allegory that occasionally connects, but more often seems like a square peg jammed into a round hole. Having visual cues like Marietta as a crystal-ball-wielding Wicked Witch Of The West is one thing, but Lynch clogging up the dialogue with Sailor talking about Jingle Dell needing some advice from the Wizard, or Big Tuna being “not exactly the Emerald City” is a little much even before Laura Palmer turns up as the Glinda The Good Witch. Road movies don’t have to follow the yellow brick road—that’s central to their appeal. They can wander.

PopMatters: But despite the violence and sociopathic behavior on display, this is also one of Lynch’s most humane, upbeat films -- if a film with a dog running off with a freshly severed hand in its mouth can be said to be upbeat. Sailor and Lula’s road trip is a deeply romantic fantasy diverted only temporarily by flying monkey interlopers, and their battered faith in their love and mutual goodness is rewarded in the end. Justice is meted out to most, if not all, of the evildoers, and the credits roll over a version of “Love Me Tender.” Compared to Lynch's bleak take on fate and human nature in, say, Eraserhead or Lost Highway, this is sunshine and sailboats.

The Film Stage: In turn, Wild at Heart finds itself primarily concerned with the construction of personal mythologies, perhaps the chief example being Sailor and his trademark snakeskin jacket, its donning in spaces both private and public accompanied by a monologue about how it represents his belief in individuality and personal freedom. (Even Lula chidingly mentions that she’s heard this about a million times already.) Of course, integral to these personal mythologies is the act of storytelling: Sailor and Lula provide backstory upon backstory about their troubled pasts that all naturally explain why these two damaged outcasts are perfect for each other. The film’s editing patterns make images from their stories (flaming homes, crying faces) bleed in and out when nobody is making so much as the slightest reference to them, giving the overriding feeling that their future will likely end up the same as their past.

Trailer

1990 was a big year for David Lynch

The craziest, most WTF moments in Wild at Heart

The David Lynch Retrospective: ‘Wild At Heart’

‘Wild at Heart’: A Twisted, Romantic Road Movie as a Lynchian Homage to ‘The Wizard of Oz’

The Tao of Nicolas Cage: Wild at Heart

Art of the Title

For some reason, Jack Nance saying "My dog barks some" is an image that I will remember to my grave.

posted by jwgh at 6:37 AM on February 15, 2018

posted by jwgh at 6:37 AM on February 15, 2018

This is probably as close as Lynch has ever come to straight-up self-parody; it's his Natural Born Killers, and I very definitely do not mean that as a compliment.

posted by Halloween Jack at 8:57 AM on February 15, 2018 [1 favorite]

posted by Halloween Jack at 8:57 AM on February 15, 2018 [1 favorite]

The extreme closeup scene between Bobby Peru and Lula still haunts me. Otherwise, all I remember from this film are images: a man on fire, the d&x shot from overhead, manic lipstick, Bobby's teeth. I'd like to see it again, but I might try to make sense of it as a story, and that's probably wasted effort.

posted by infinitewindow at 10:26 AM on February 19, 2018

posted by infinitewindow at 10:26 AM on February 19, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

"Baroque floridity" is one of the most colorful terms I have seen to describe Cage's acting. He did some great stuff in the 90's (probably the best of which was Kiss of Death) and I'm fine with his Elvis schtick, he's definitely good at that. I think I had seen Willem Dafoe in a few films when this came out (To Live and Die in L.A. and Mississippi Burning for sure), but this was the one that made me decide that I needed to see everything he appears in. He was so strait-laced in those other films that his performance in this one was shocking.

posted by heatvision at 3:50 AM on February 15, 2018