A Clockwork Orange (1971)

May 22, 2018 8:36 PM - Subscribe

In the future, a sadistic gang leader is imprisoned and volunteers for a conduct-aversion experiment, but it doesn't go as planned.

Variety: "A Clockwork Orange" is a brilliant nightmare. Stanley Kubrick's latest film takes the heavy realities of the 'do-your-thing' and 'law-and-order' syndromes, runs them through a cinematic centrifuge, and spews forth the commingled comic horrors of a regulated society. Uncomfortably proximate, disturbingly plausible and obliquely resolved, the film employs outrageous vulgarity, stark brutality and some sophisticated comedy to make an opaque argument for the preservation of respect for man's free will - even to do wrong.

NYTimes: “A Clockwork Orange” is so beautiful to look at and to hear that it dazzles the senses and the mind, even as it turns the old real red vino to ice: Alex and his friends having a rumble with a rival gang to the tune of Rossini's ‘’The Thieving Magpie,” or preparing a gang rape in the home of a definitely upper‐class writer as Alex does a lyric soft‐shoe (into the stomach and face of the writer), singing “Sing in’ in the Rain.” That's the sort of thing that makes Alex feel all nice and warm in his guttywuts.

McDowell is splendid as tomorrow's child, but it is always Mr. Kubrick's picture, which is even technically more interesting than “2001.” Among other devices, Mr. Ku brick constantly uses what assume to be a wide‐angle lens to distort space relation ships within scenes, so that the disconnection between lives, and between people and environment, becomes an actual, literal fact.

At one point in his therapy, Alex says: “The colors of the real world only become real when you viddy them in a film.” “A Clockwork Orange” makes real and important the kind of fears simply exploited by other, much lesser films.

Roger Ebert: Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.

I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we've all run across a few times in our lives -- usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting. He was the kid who always seemed to know more about sex than anyone else, too -- and especially about how dirty it was.

Slant: One of the great criticisms heaped against A Clockwork Orange is that Stanley Kubrick glorifies a certain kind of amoral violence, presenting it to the viewer in a spectacular, operatic, colorful, and exquisitely photographed manner. Malcolm McDowell, at the top of his game as Alex the thug, gleefully narrates his way through the ultra-violence his character commits in the first third of the movie. A particularly obscene atrocity is when he and his gang of droogs rape a woman and brutalize her husband while gallivanting about the house singing “Singin’ in the Rain.” Alex throws himself into the act with giddy exuberance, but does anyone honestly believe that we’re meant to laugh along with Alex’s joie de vivre as he behaves like a savage?

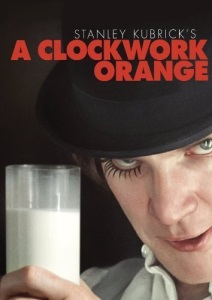

Certainly, no punches are pulled in this queasy home invasion sequence. The thugs wear creepy Halloween masks and, in their white suits with elaborate codpieces and bowler hats, are positively grotesque. But before we see Alex unleash his dark side, our first glimpse of him—in the opening shot of the movie—has him looking straight into the camera, toasting the audience with a glass of milk at the Korova Milk Bar. He’s seen as handsome, charismatic, and while he’s completely unaware of the vast discrepancy between his buoyant narration and his workaday acts of thievery, brutality, and deviancy (speaking directly to the audience as if he were the young hero of a Charles Dickens novel, even referring to himself as “your humble narrator”), he casts a spell over the viewer as if to say, “Come along with me, little ones.” He is, in effect, inviting us to enjoy, as we do when we tune in to reality television shows and tabloid newspapers, watching debasement as entertainment. It’s a nasty recognition of the distance one has as a spectator, laughing at another’s expense. If you watch Clockwork Orange and see that this is the game Kubrick is playing with us, giving us an avenue into understanding a corrosion of society, the film may be appreciated as his finest masterwork in a career full of them. Certainly, it’s his most human film, right next to Lolita in its refusal to judge its central character’s sickness. That’s the job of the audience. Anyone who doesn’t feel up to that job might throw up their hands and accuse Kubrick of being immoral, when in fact the sense of being a morality play is hard-wired right into the structure of Clockwork Orange.

Empire: It's all stylised, from Burgess' invented pidgin Russian to 2001-style slow tracks, through sculpturally-perfect sets (like many Kubrick movies, the story could be told through decor alone) and exaggerated, grotesque performances (on a par with those of Dr. Strangelove). Made in 1971, based on a novel from 1962, A Clockwork Orange resonates across the years. Its future is quaint now, with Alexander pecking out "subversive literature" on a giant IBM typewriter, "lovely, lovely Ludwig Van" on vinyl, and Alex stranded alone in a vast and empty National Health hospital ward. However, the world of "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" is very much with us: a housing estate where classical murals are obscenely vandalised, passersby are rare and yobs loll about with nothing better to do than hurt people.

Cinephilia and Beyond: A Clockwork Orange is a complex vision abounding in stylistically choreographed violence which never has the pornographic quality that several critics labelled it with. Carried by an astonishing performance from then-27-year-old Malcolm McDowell, who got the role thanks to his effort in Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968), shot by John Alcott (Kubrick’s skilled associate from 2001, Barry Lyndon and The Shining), enriched by the melodies of Gioachino Rossini and Ludwig van Beethoven and edited by Bill Butler, this film is a masterfully executed window into the society of both the future and the present. The unmistakable dreamlike quality of the movie stems from Kubrick’s intentional use of wide-angle lenses, intended for the distortion of space relationships on screen and the enhancement of the feeling of anarchy and disconnection between the screen’s occupants, while the use of slow motion adds to the aesthetic value of otherwise brutal shots unveiling the protagonist’s rotten, destructive core. A Clockwork Orange is a film touching upon many subjects, not the least important of which is the one concerning the free will of people. If a technologically advanced society eliminates the possibility of committing crimes, to what degree are members of this community dehumanized, with the elementary choice between good and evil taken away from their hands? Kubrick’s film is one of those landmark movies that opened up the possibility for the depiction of violence in the cinema, elevating the art and freeing its hands to imitate life as faithfully as possible. Upon seeing the film, Luis Buñuel stated he was predisposed against it at first, but then realized “it’s only a movie about what the modern world really means.”

Trailer

Malcolm McDowell & Anthony Burgess Discuss 'A Clockwork Orange' in This 1972 Doc

'A Clockwork Orange' strikes 40

A Clockwork Orange: the look that shook the nation

The film sets and furniture of A Clockwork Orange: “A real horrorshow” Part 1

The Real Reason Why 'A Clockwork Orange' Was So Disturbing

The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange

The Real Cure: A Clockwork Orange’s Missing Ending

Chaos, oppression, and the grim worlds of A Clockwork Orange and THX-1138

Variety: "A Clockwork Orange" is a brilliant nightmare. Stanley Kubrick's latest film takes the heavy realities of the 'do-your-thing' and 'law-and-order' syndromes, runs them through a cinematic centrifuge, and spews forth the commingled comic horrors of a regulated society. Uncomfortably proximate, disturbingly plausible and obliquely resolved, the film employs outrageous vulgarity, stark brutality and some sophisticated comedy to make an opaque argument for the preservation of respect for man's free will - even to do wrong.

NYTimes: “A Clockwork Orange” is so beautiful to look at and to hear that it dazzles the senses and the mind, even as it turns the old real red vino to ice: Alex and his friends having a rumble with a rival gang to the tune of Rossini's ‘’The Thieving Magpie,” or preparing a gang rape in the home of a definitely upper‐class writer as Alex does a lyric soft‐shoe (into the stomach and face of the writer), singing “Sing in’ in the Rain.” That's the sort of thing that makes Alex feel all nice and warm in his guttywuts.

McDowell is splendid as tomorrow's child, but it is always Mr. Kubrick's picture, which is even technically more interesting than “2001.” Among other devices, Mr. Ku brick constantly uses what assume to be a wide‐angle lens to distort space relation ships within scenes, so that the disconnection between lives, and between people and environment, becomes an actual, literal fact.

At one point in his therapy, Alex says: “The colors of the real world only become real when you viddy them in a film.” “A Clockwork Orange” makes real and important the kind of fears simply exploited by other, much lesser films.

Roger Ebert: Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.

I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we've all run across a few times in our lives -- usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting. He was the kid who always seemed to know more about sex than anyone else, too -- and especially about how dirty it was.

Slant: One of the great criticisms heaped against A Clockwork Orange is that Stanley Kubrick glorifies a certain kind of amoral violence, presenting it to the viewer in a spectacular, operatic, colorful, and exquisitely photographed manner. Malcolm McDowell, at the top of his game as Alex the thug, gleefully narrates his way through the ultra-violence his character commits in the first third of the movie. A particularly obscene atrocity is when he and his gang of droogs rape a woman and brutalize her husband while gallivanting about the house singing “Singin’ in the Rain.” Alex throws himself into the act with giddy exuberance, but does anyone honestly believe that we’re meant to laugh along with Alex’s joie de vivre as he behaves like a savage?

Certainly, no punches are pulled in this queasy home invasion sequence. The thugs wear creepy Halloween masks and, in their white suits with elaborate codpieces and bowler hats, are positively grotesque. But before we see Alex unleash his dark side, our first glimpse of him—in the opening shot of the movie—has him looking straight into the camera, toasting the audience with a glass of milk at the Korova Milk Bar. He’s seen as handsome, charismatic, and while he’s completely unaware of the vast discrepancy between his buoyant narration and his workaday acts of thievery, brutality, and deviancy (speaking directly to the audience as if he were the young hero of a Charles Dickens novel, even referring to himself as “your humble narrator”), he casts a spell over the viewer as if to say, “Come along with me, little ones.” He is, in effect, inviting us to enjoy, as we do when we tune in to reality television shows and tabloid newspapers, watching debasement as entertainment. It’s a nasty recognition of the distance one has as a spectator, laughing at another’s expense. If you watch Clockwork Orange and see that this is the game Kubrick is playing with us, giving us an avenue into understanding a corrosion of society, the film may be appreciated as his finest masterwork in a career full of them. Certainly, it’s his most human film, right next to Lolita in its refusal to judge its central character’s sickness. That’s the job of the audience. Anyone who doesn’t feel up to that job might throw up their hands and accuse Kubrick of being immoral, when in fact the sense of being a morality play is hard-wired right into the structure of Clockwork Orange.

Empire: It's all stylised, from Burgess' invented pidgin Russian to 2001-style slow tracks, through sculpturally-perfect sets (like many Kubrick movies, the story could be told through decor alone) and exaggerated, grotesque performances (on a par with those of Dr. Strangelove). Made in 1971, based on a novel from 1962, A Clockwork Orange resonates across the years. Its future is quaint now, with Alexander pecking out "subversive literature" on a giant IBM typewriter, "lovely, lovely Ludwig Van" on vinyl, and Alex stranded alone in a vast and empty National Health hospital ward. However, the world of "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" is very much with us: a housing estate where classical murals are obscenely vandalised, passersby are rare and yobs loll about with nothing better to do than hurt people.

Cinephilia and Beyond: A Clockwork Orange is a complex vision abounding in stylistically choreographed violence which never has the pornographic quality that several critics labelled it with. Carried by an astonishing performance from then-27-year-old Malcolm McDowell, who got the role thanks to his effort in Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968), shot by John Alcott (Kubrick’s skilled associate from 2001, Barry Lyndon and The Shining), enriched by the melodies of Gioachino Rossini and Ludwig van Beethoven and edited by Bill Butler, this film is a masterfully executed window into the society of both the future and the present. The unmistakable dreamlike quality of the movie stems from Kubrick’s intentional use of wide-angle lenses, intended for the distortion of space relationships on screen and the enhancement of the feeling of anarchy and disconnection between the screen’s occupants, while the use of slow motion adds to the aesthetic value of otherwise brutal shots unveiling the protagonist’s rotten, destructive core. A Clockwork Orange is a film touching upon many subjects, not the least important of which is the one concerning the free will of people. If a technologically advanced society eliminates the possibility of committing crimes, to what degree are members of this community dehumanized, with the elementary choice between good and evil taken away from their hands? Kubrick’s film is one of those landmark movies that opened up the possibility for the depiction of violence in the cinema, elevating the art and freeing its hands to imitate life as faithfully as possible. Upon seeing the film, Luis Buñuel stated he was predisposed against it at first, but then realized “it’s only a movie about what the modern world really means.”

Trailer

Malcolm McDowell & Anthony Burgess Discuss 'A Clockwork Orange' in This 1972 Doc

'A Clockwork Orange' strikes 40

A Clockwork Orange: the look that shook the nation

The film sets and furniture of A Clockwork Orange: “A real horrorshow” Part 1

The Real Reason Why 'A Clockwork Orange' Was So Disturbing

The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange

The Real Cure: A Clockwork Orange’s Missing Ending

Chaos, oppression, and the grim worlds of A Clockwork Orange and THX-1138

I respect the hell out of the craft of this movie, and McDowell's performance really is astonishing; but I think there's a good chance I'll make it the rest of the way through my life without watching it again because it's so tough and queasy to sit through.

One thing that really sticks with me: for a long time, I casually thought Orange must have been made in 76 or 77 since its aesthetics are so close to first-wave punk aesthetics. Then I looked it up and saw it was way earlier than that, and nodded and told myself, "yeah, that's what it means to be an influential visionary."

Also: Burgess' book is really good, and substantially different in the end. It's tough to rewire your brain to parse all the Nadsat dialogue, but it's a cool feeling when it clicks and starts making sense.

Also also: David Bowie liked this movie.

posted by the phlegmatic king at 7:19 AM on May 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

One thing that really sticks with me: for a long time, I casually thought Orange must have been made in 76 or 77 since its aesthetics are so close to first-wave punk aesthetics. Then I looked it up and saw it was way earlier than that, and nodded and told myself, "yeah, that's what it means to be an influential visionary."

Also: Burgess' book is really good, and substantially different in the end. It's tough to rewire your brain to parse all the Nadsat dialogue, but it's a cool feeling when it clicks and starts making sense.

Also also: David Bowie liked this movie.

posted by the phlegmatic king at 7:19 AM on May 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

I might revisit this movie at some point, but my reluctance to do so for many if not most of the reasons that so disgusted Ebert is bolstered by a sense of shame for having adopted this movie as a cultural touchstone as a teenager out of a sort of proto-edgelordism, the strong feeling that it was worth venerating simply because the popular kids wouldn't sit through five minutes of it. Yeah, we all did things as kids that were embarrassing, but adopting the catchphrases and mannerisms of a fictional rapist and murderer are on a different order than that faddish haircut you got in middle school. The story does have a lot of meat to it, and McDowell's performance goes beyond his natural charisma, which is considerable and always somewhat disturbing; Alex seems genuinely changed by the treatment, and Kubrick does a good job in setting up parallel scenes before and after.

posted by Halloween Jack at 7:41 AM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

posted by Halloween Jack at 7:41 AM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

My brain no work so good, so perhaps I'm missing it, but is there anything there about how not only did Kubrick ban the film in the UK for decades, possibly out of exasperation, but an illicit screening at the legendary Scala Cinema in King's Cross led to it being sued and shut down.

posted by Grangousier at 8:07 AM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

posted by Grangousier at 8:07 AM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

It is genuinely a really tough film, really hard to watch, especially as its protagonist is not just gleefully violent but sexually violent. I think it is clear that Kubrick did not sympathize or glorify this, as I have never seen a colder, less sympathetic treatment of a protagonist, although the film does take pains to place Alex in a larger, consistently abusive context -- he is groped by his parole officer, Mr. Deltoid, and generally mistreated and dehumanized in prison.

I have never been able to put my finger on why those scenes have a satiric sensibility while Alex's crimes is more self-consciously florid and slightly psychedelic, but maybe Kubrick was representing the fact that Alex was on drug-infused milk-plus during his crimes and, without that influence, abuse becomes squalid and weird and route.

I can't shake the feeling that these institutional scenes profoundly influenced the later films of Monty Python. All of Meaning of Life feel like its lifts directly from the prison scenes in this film.

posted by maxsparber at 8:17 AM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

I have never been able to put my finger on why those scenes have a satiric sensibility while Alex's crimes is more self-consciously florid and slightly psychedelic, but maybe Kubrick was representing the fact that Alex was on drug-infused milk-plus during his crimes and, without that influence, abuse becomes squalid and weird and route.

I can't shake the feeling that these institutional scenes profoundly influenced the later films of Monty Python. All of Meaning of Life feel like its lifts directly from the prison scenes in this film.

posted by maxsparber at 8:17 AM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

I feel a connection between the hobo beatdown and the warehouse (rooftop? back alley? I have the image, but not the details) rape/gangfight with RoboCop for some reason. Maybe subconsciously in hindsight I'm hoping he shows up in the earlier movie.

posted by rhizome at 2:27 PM on May 23, 2018

posted by rhizome at 2:27 PM on May 23, 2018

It was a difficult movie to see for British people of my generation. The first time I saw it was a very scratched VHS in a hotel room at an SF con in Glasgow around 1990, and even then, the fact that the movie was being shown at all was only spread through word of mouth.

For a long time, one of the cinemas in Amsterdam would show the movie every weekend as one of its midnight screenings, and I watched it there just after I moved here (again, the print was very scratched). I could never work out whether it was some kind of protest against the movie being banned in the UK (which it still was at the time), or a canny way to get some easy money from British tourists.

posted by daveje at 3:17 PM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

For a long time, one of the cinemas in Amsterdam would show the movie every weekend as one of its midnight screenings, and I watched it there just after I moved here (again, the print was very scratched). I could never work out whether it was some kind of protest against the movie being banned in the UK (which it still was at the time), or a canny way to get some easy money from British tourists.

posted by daveje at 3:17 PM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

Screening this movie got my high school film club shut down.

It was worth it.

posted by Phobos the Space Potato at 4:14 PM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

It was worth it.

posted by Phobos the Space Potato at 4:14 PM on May 23, 2018 [5 favorites]

What year? When i was a senior in 1985(LA suburbs) I dressed up as Alex for the Halloween( my response to the junior boy who told me that I couldn't be him because " you're a girl" was "so?" ) school contest without incident.

posted by brujita at 4:32 PM on May 23, 2018 [3 favorites]

posted by brujita at 4:32 PM on May 23, 2018 [3 favorites]

This would have been northern CA in 1999. Also a Catholic school, which may be why we found the brainwashing theme so appealing, edgy little nonconformists that we were.

posted by Phobos the Space Potato at 5:12 PM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

posted by Phobos the Space Potato at 5:12 PM on May 23, 2018 [1 favorite]

I've long felt that the point of this movie isn't completely in Alex's journey, but in Dim and Georgie's. That is, the real clockwork orange of it all is that as a government slips into fascism, it'll won't care what sort of thug it'll hire to knock heads around. Or to be it's media darling.

posted by Catblack at 8:40 PM on May 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

posted by Catblack at 8:40 PM on May 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

I saw this in the UK when it was first released, when I was at Reading university , The next day, I had to go up to London, and on the platform across from me saw three young men in full droog regalia - scared the willies out of me.

As others have said, I liked the book much better than the film, especially for the language, and at the end, where Alex just settles down and becomes a normal person - because everyone does awful things when they are young and stupid. there is a sort of misanthropic chill that comes across from Kubrick's films that I find myself less and less in sympathy with as I grow older, possibly for similar reasons.

The fact that my name is Alex makes my feelings about the main character a little ambiguous, and for a while after reading the book I did go around referring to myself as "your humble friend and narrator", just to annoy people, because I was young and stupid too.

posted by Fuchsoid at 7:42 PM on May 24, 2018 [2 favorites]

As others have said, I liked the book much better than the film, especially for the language, and at the end, where Alex just settles down and becomes a normal person - because everyone does awful things when they are young and stupid. there is a sort of misanthropic chill that comes across from Kubrick's films that I find myself less and less in sympathy with as I grow older, possibly for similar reasons.

The fact that my name is Alex makes my feelings about the main character a little ambiguous, and for a while after reading the book I did go around referring to myself as "your humble friend and narrator", just to annoy people, because I was young and stupid too.

posted by Fuchsoid at 7:42 PM on May 24, 2018 [2 favorites]

When I worked at Blockbuster, this was the one title we carried that had an unwritten store policy of 100%, no-questions-asked exchange for a free rental of another title. Didn't matter if you were late in returning it, didn't matter if your account had rented it before, didn't matter if the film you wanted to exchange for was a more expensive new release, didn't matter if you had been warned ahead of time that the film wasn't for everyone, all you had to do was to bring it back and say the words "I had rented Clockwork Orange..." and before you could finish the sentence, whichever associate you were talking too would already have reflexively begun the exchange process.

My own personal version of the warning was: "If you want to know what I thought about the film, I appreciate it for its artistic merits, but it's not for everyone. It starts out with a gang of hooligans beating a drunken bum to within an inch of his life, and yet, that scene is actually the closest the film ever gets to a socially redeeming moment. It's all a steady downward spiral from there, just when you think it can't possibly get worse, it does, over and over again."

Unrelated to my time at Blockbuster, my first time seeing it, I had made the mistake of thinking it might be a good first date movie. With the right kind of partner, in rare cases, I suppose that it could be, but in my case, there was no second date.

posted by radwolf76 at 7:32 PM on May 25, 2018 [3 favorites]

My own personal version of the warning was: "If you want to know what I thought about the film, I appreciate it for its artistic merits, but it's not for everyone. It starts out with a gang of hooligans beating a drunken bum to within an inch of his life, and yet, that scene is actually the closest the film ever gets to a socially redeeming moment. It's all a steady downward spiral from there, just when you think it can't possibly get worse, it does, over and over again."

Unrelated to my time at Blockbuster, my first time seeing it, I had made the mistake of thinking it might be a good first date movie. With the right kind of partner, in rare cases, I suppose that it could be, but in my case, there was no second date.

posted by radwolf76 at 7:32 PM on May 25, 2018 [3 favorites]

I hate this movie deeply. Although aesthetically very sophisticated, it seems to me incredibly immature and dresses up a pornified violence in artistic trappings. Visually and aurally it is rather perfect. Wendy Carlos' soundtrack is bizarre, immersive and powerful. The costumes and sets brilliant. I guess the acting is good? It's hard to evaluate in something so stylized - it's more like theater than film.

But what the fuck is A Clockwork Orange? It's just a a parade of rapes and beatings, and then an extended torture scene, saying what? Meaning what? In the book I could enjoy the artfulness of the linguistics and perhaps because it was on paper not screen it was less assaultive to the audience.

This movie just seems like toxic masculinity on a plate: nothing means anything so here's some male brutality and violence designed to be stunning.

posted by latkes at 9:47 AM on May 26, 2018 [1 favorite]

But what the fuck is A Clockwork Orange? It's just a a parade of rapes and beatings, and then an extended torture scene, saying what? Meaning what? In the book I could enjoy the artfulness of the linguistics and perhaps because it was on paper not screen it was less assaultive to the audience.

This movie just seems like toxic masculinity on a plate: nothing means anything so here's some male brutality and violence designed to be stunning.

posted by latkes at 9:47 AM on May 26, 2018 [1 favorite]

Viddy well little brother

posted by growabrain at 1:41 AM on May 27, 2018 [2 favorites]

posted by growabrain at 1:41 AM on May 27, 2018 [2 favorites]

Yeah, I another of those Brits where the lack of opportunity to see if for years had really built up the film in my imagination... only had the book, the soundtrack LP (which I played quite a bit during student years) and the odd still and write up in movie books.

And when I finally got to see it...? I didn't really expect it to be so camp.

I should really go back and give it another look, but as often with genius but chilly impersonal Kubrick the urge is not strong.

But the book is real horrorshow

posted by fearfulsymmetry at 12:41 AM on May 28, 2018

And when I finally got to see it...? I didn't really expect it to be so camp.

I should really go back and give it another look, but as often with genius but chilly impersonal Kubrick the urge is not strong.

But the book is real horrorshow

posted by fearfulsymmetry at 12:41 AM on May 28, 2018

But what the fuck is A Clockwork Orange? It's just a a parade of rapes and beatings, and then an extended torture scene, saying what? Meaning what? In the book I could enjoy the artfulness of the linguistics and perhaps because it was on paper not screen it was less assaultive to the audience.

I saw an interview a long time ago where Burgess talked about creating Nadsat specifically to distance the reader and avoid exactly this.

posted by Pope Guilty at 7:00 AM on May 28, 2018 [1 favorite]

I saw an interview a long time ago where Burgess talked about creating Nadsat specifically to distance the reader and avoid exactly this.

posted by Pope Guilty at 7:00 AM on May 28, 2018 [1 favorite]

I very recently saw this movie for the first time. I don't enjoy cinematic violence, and can't stand to see violence glamorized. However, I do appreciate violence in films when it's important to communicate a character's personality, choices, and the consequences of his actions.

I found this movie to be an incredible, subversive exploration of morality and violence. It raises questions about justice, free will, and humanity. Does Alex "deserve" punishment? What is the moral status of the social forces that subject him to punishment? How much punishment? Does the motivation of those people matter? Does the audience's emotional state matter? To me, these are the types of questions that science fiction should ask, because they're the edge cases.

posted by overeducated_alligator at 11:25 AM on May 29, 2018 [4 favorites]

I found this movie to be an incredible, subversive exploration of morality and violence. It raises questions about justice, free will, and humanity. Does Alex "deserve" punishment? What is the moral status of the social forces that subject him to punishment? How much punishment? Does the motivation of those people matter? Does the audience's emotional state matter? To me, these are the types of questions that science fiction should ask, because they're the edge cases.

posted by overeducated_alligator at 11:25 AM on May 29, 2018 [4 favorites]

I can't shake the feeling that these institutional scenes profoundly influenced the later films of Monty Python.

Definitely. If nothing else, Mr Deltoid is pure Python.

posted by Jon Mitchell at 9:19 PM on May 29, 2018

Definitely. If nothing else, Mr Deltoid is pure Python.

posted by Jon Mitchell at 9:19 PM on May 29, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by rhizome at 9:39 PM on May 22, 2018 [3 favorites]