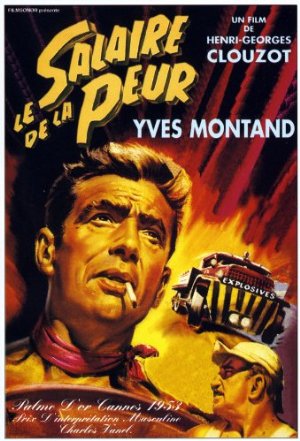

The Wages of Fear (1953)

June 1, 2016 6:23 PM - Subscribe

In a decrepit South American village, men are hired to transport an urgent nitroglycerine shipment without the equipment that would make it safe.

The Guardian: Set in an unnamed south American country, the action starts in a small town with an airfield where we are introduced to four shady characters anxious to get out, but minus the money for a plane ticket. A very venal oil company offers them $2,000 each to drive trucks loaded with nitroglycerine over rough mountain roads to an oilfield that is on fire. The roads are awful. The hazards are unlimited. And the nitro, sweating in the heat, itches to explode long before it gets to the oilfield.

The way Clouzot films this process (in a movie of over two and a half hours) is a model of grinding, unrelieved suspense. The film was shot in black and white, not in south America but in the south of France. And it is now well over 50 years old.

Yet the inspired calculation of action and agonised human reaction is irresistible and inescapable. It is a film that leaves the audience shattered and exhausted.

Slant: Our ragtag quartet doesn't hit the road until the film's second hour, whereupon a series of breathtaking set pieces ensues, one more elaborate (and protracted) than the previous, as the trucks negotiate increasingly inhospitable terrain and Clouzot takes his time with every detail, tailgating at breakneck pace across uneven ground known as “the washboard,” navigating a partially constructed road extension that's little more than rotten timber jutting out over a void, which quickly becomes a domino-fall of unintended consequences. Like the cantina confrontation, this sequence showcases Clouzot's rapid-fire montage, breaking down a simple motion like Mario jumping from the platform onto the hillside into its constituent parts, a three-shot montage that ends with a knowing flourish as Mario kicks a spray of dirt into the camera lens.

Culture Vulture: It is a testament to Clouzot's instincts for psychological tension that he paces the first half of the film in a seemingly aimless fashion. As we observe the desultory hostilities that percolate up from the poverty and despair – indeed from the aimlessness itself – we begin to share Mario's itchiness to escape this godawful hellhole. When Mario and Jo finally join together as partners on one of the nitro trucks, the free-floating anxiety we've been experiencing solidifies into genuine suspense and tightens around the storyline, as well as around the film's pacing and editing.

Senses of Cinema: The action scenes are as good as any shot until the digital age and the trucks themselves become characters, as did the old Leyland Badger in John Heyer’s marvellous documentary The Back of Beyond, released a year later (1954), and set in an equally hostile outback Australia.

One sequence sums up the power of this great film and is itself unforgettable – unless you blink and miss it. Jo rolls out a cigarette when suddenly the tobacco seems to fly off the paper. Why? The scene and its payoff is one of the great moments in cinema metaphor – and imagination.

Deep Focus Review: That Clouzot’s protagonists select a fatalistic mission makes the road no less daunting, or involving, or thrilling for the viewer. Split between two trucks, the men divide themselves as an insurance policy. Should one truck suddenly detonate, the other could still make it through. Mario and Jo take the lead, with Luigi and Bimba following a half an hour behind. Each man is stripped down to the barest version of himself once on the road, as fear removes layer after layer of built-up fronts, disrobing him until nothing is left but the raw man. Herein we see where some endure and others fall to pieces. Charles Vanel’s performance as Jo is the film’s best illustration of this; his character loses the most, having masqueraded himself as a brave, experienced workman to hide his cowardly interior. Clouzot originally hoped to fill the role with France’s equivalent to Humphrey Bogart, Jean Gabin from Grand Illusion (1937) and Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), but the screen icon turned down the role, worried that playing a coward might tarnish his onscreen reputation. Furthermore, surely Gabin would have stolen the picture away from Yves Montand in the central role by presence alone; whereas Vanel, who disappears into his harrowing performance, committing himself to the depths of spinelessness and turmoil the role demands.

AV Club: Vanel, playing a guy so paralyzed with fear that he can’t even flee the truck, arguably goes over the top in his depiction of controlled panic, shuddering as if he were in a massage chair on its highest speed, and screwing his eyes tightly shut at each prospective hit. But this is one of those cases where you do need to know what happened earlier in the movie, which spends almost its entire first half establishing this character as an utterly fearless badass of the first degree. He’s comfortable handing his loaded pistol to an enemy and daring him to shoot—and then slapping him hard in the face when he hesitates, and daring him again—yet he goes to jelly at the sight of a small rock tumbling in his direction. That’s the whole point; his exaggerated cowardice in this scene counterbalances the exaggerated machismo seen earlier. If even he can’t handle the stress, this nail-biter of a film implies, what possible chance do we have?

Film School Rejects: It’s not for nothing that The Wages of Fear opens with a shot of beetles tied together with a string held by a young boy. The insects’ fates are as irrelevant as they are ensured. The men here are no better off than those bugs, trapped on tethers controlled by others above and beyond their station, but it’s in their struggle to break those bonds that these crass, rough bastards show their unwavering humanity.

Roger Ebert: One thing that establishes "The Wages of Fear" as a film from the early 1950s, and not from today, is its attitude toward happy endings. Modern Hollywood thrillers cannot end in tragedy for its heroes, because the studios won't allow it. "The Wages of Fear" is completely free to let anything happen to any of its characters, and if all four are not dead when the nitro reaches the blazing oil well, it may be because Clouzot is even more deeply ironic than we expect. The last scene, where a homebound truck is intercut with a celebration while a Strauss waltz plays on the radio, is a reminder of how much Hollywood has traded away by insisting on the childishness of the obligatory happy ending.

Trailer

The Guardian: Set in an unnamed south American country, the action starts in a small town with an airfield where we are introduced to four shady characters anxious to get out, but minus the money for a plane ticket. A very venal oil company offers them $2,000 each to drive trucks loaded with nitroglycerine over rough mountain roads to an oilfield that is on fire. The roads are awful. The hazards are unlimited. And the nitro, sweating in the heat, itches to explode long before it gets to the oilfield.

The way Clouzot films this process (in a movie of over two and a half hours) is a model of grinding, unrelieved suspense. The film was shot in black and white, not in south America but in the south of France. And it is now well over 50 years old.

Yet the inspired calculation of action and agonised human reaction is irresistible and inescapable. It is a film that leaves the audience shattered and exhausted.

Slant: Our ragtag quartet doesn't hit the road until the film's second hour, whereupon a series of breathtaking set pieces ensues, one more elaborate (and protracted) than the previous, as the trucks negotiate increasingly inhospitable terrain and Clouzot takes his time with every detail, tailgating at breakneck pace across uneven ground known as “the washboard,” navigating a partially constructed road extension that's little more than rotten timber jutting out over a void, which quickly becomes a domino-fall of unintended consequences. Like the cantina confrontation, this sequence showcases Clouzot's rapid-fire montage, breaking down a simple motion like Mario jumping from the platform onto the hillside into its constituent parts, a three-shot montage that ends with a knowing flourish as Mario kicks a spray of dirt into the camera lens.

Culture Vulture: It is a testament to Clouzot's instincts for psychological tension that he paces the first half of the film in a seemingly aimless fashion. As we observe the desultory hostilities that percolate up from the poverty and despair – indeed from the aimlessness itself – we begin to share Mario's itchiness to escape this godawful hellhole. When Mario and Jo finally join together as partners on one of the nitro trucks, the free-floating anxiety we've been experiencing solidifies into genuine suspense and tightens around the storyline, as well as around the film's pacing and editing.

Senses of Cinema: The action scenes are as good as any shot until the digital age and the trucks themselves become characters, as did the old Leyland Badger in John Heyer’s marvellous documentary The Back of Beyond, released a year later (1954), and set in an equally hostile outback Australia.

One sequence sums up the power of this great film and is itself unforgettable – unless you blink and miss it. Jo rolls out a cigarette when suddenly the tobacco seems to fly off the paper. Why? The scene and its payoff is one of the great moments in cinema metaphor – and imagination.

Deep Focus Review: That Clouzot’s protagonists select a fatalistic mission makes the road no less daunting, or involving, or thrilling for the viewer. Split between two trucks, the men divide themselves as an insurance policy. Should one truck suddenly detonate, the other could still make it through. Mario and Jo take the lead, with Luigi and Bimba following a half an hour behind. Each man is stripped down to the barest version of himself once on the road, as fear removes layer after layer of built-up fronts, disrobing him until nothing is left but the raw man. Herein we see where some endure and others fall to pieces. Charles Vanel’s performance as Jo is the film’s best illustration of this; his character loses the most, having masqueraded himself as a brave, experienced workman to hide his cowardly interior. Clouzot originally hoped to fill the role with France’s equivalent to Humphrey Bogart, Jean Gabin from Grand Illusion (1937) and Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), but the screen icon turned down the role, worried that playing a coward might tarnish his onscreen reputation. Furthermore, surely Gabin would have stolen the picture away from Yves Montand in the central role by presence alone; whereas Vanel, who disappears into his harrowing performance, committing himself to the depths of spinelessness and turmoil the role demands.

AV Club: Vanel, playing a guy so paralyzed with fear that he can’t even flee the truck, arguably goes over the top in his depiction of controlled panic, shuddering as if he were in a massage chair on its highest speed, and screwing his eyes tightly shut at each prospective hit. But this is one of those cases where you do need to know what happened earlier in the movie, which spends almost its entire first half establishing this character as an utterly fearless badass of the first degree. He’s comfortable handing his loaded pistol to an enemy and daring him to shoot—and then slapping him hard in the face when he hesitates, and daring him again—yet he goes to jelly at the sight of a small rock tumbling in his direction. That’s the whole point; his exaggerated cowardice in this scene counterbalances the exaggerated machismo seen earlier. If even he can’t handle the stress, this nail-biter of a film implies, what possible chance do we have?

Film School Rejects: It’s not for nothing that The Wages of Fear opens with a shot of beetles tied together with a string held by a young boy. The insects’ fates are as irrelevant as they are ensured. The men here are no better off than those bugs, trapped on tethers controlled by others above and beyond their station, but it’s in their struggle to break those bonds that these crass, rough bastards show their unwavering humanity.

Roger Ebert: One thing that establishes "The Wages of Fear" as a film from the early 1950s, and not from today, is its attitude toward happy endings. Modern Hollywood thrillers cannot end in tragedy for its heroes, because the studios won't allow it. "The Wages of Fear" is completely free to let anything happen to any of its characters, and if all four are not dead when the nitro reaches the blazing oil well, it may be because Clouzot is even more deeply ironic than we expect. The last scene, where a homebound truck is intercut with a celebration while a Strauss waltz plays on the radio, is a reminder of how much Hollywood has traded away by insisting on the childishness of the obligatory happy ending.

Trailer

Remade in 1977 by William Friedkin as Sorceror, with Roy Scheider in the lead. Actually, Friedkin always claimed he was not remaking the Clouzot film but re-adapting the Arnaud novel. In either case, it's not much of a match for the 1952 film.

posted by ubiquity at 6:07 AM on June 2, 2016

posted by ubiquity at 6:07 AM on June 2, 2016

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by ubiquity at 6:02 AM on June 2, 2016