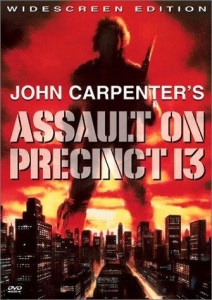

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)

May 8, 2018 7:17 PM - Subscribe

An unlikely partnership between a Highway Patrol Officer, two criminals and a station secretary is formed to defend a defunct Los Angeles precinct office against a siege by a bloodthirsty street gang.

Deadspin: John Carpenter’s original Assault on Precinct 13 is one of the greatest zombie movies of all time, and there’s not a single zombie in it. The elements are all there: The chilling synth score, a cast of randoms thrown together by chance, an isolated siege site, the narrow escapes and eerie moments before all hell breaks loose, the characters dropping like flies and battling an overwhelming numbers of enemies, the scenes where our heroes hopelessly try to block off the entrances, and the scenes where the bad guys finally break through. But instead of actually making a zombie movie —something that barely existed in 1976, when the movie came out— Carpenter used those zombie movie techniques to tell a story about wayward gang youth, a pretty mundane subject in the hands of just about any other director.

AV Club: John Carpenter uses Rio Bravo as the template for his 1976 sophomore directorial effort Assault On Precinct 13, a neo-Western about a police station under attack from a Los Angeles gang known as Street Thunder. That barrage is motivated by a series of events that Carpenter stages with mounting tension, and suggests a world ensnared in a ceaseless cycle of slaughter. In response to faceless cops murdering their comrades, gang members go on the prowl, looking to retaliate against innocent bystanders. They eventually settle on an ice-cream truck driver and—in an infamous, still-shocking scene—a young girl, whose fatal bullet to the chest is filmed straight on, fully establishing Street Thunder’s (and the film’s) ruthlessness.

Violence begets violence in Assault On Precinct 13, as the father of the slain girl guns down her killer, and then flees to a precinct in slummy Anderson, California, that’s in the process of being shut down (hence few weapons or staffers), and under the command of newly assigned Lieutenant Bishop (Austin Stoker). Complicating matters further, a trio of convicts, on its way to another prison, has made a pit stop at Precinct 13. They’re led by Napoleon Wilson (Darwin Joston), a cocky, wisecracking criminal whose recurring requests for cigarettes and refusal to explain the origins of his first name provide a strain of smart-ass humor.

Carpenter’s script lays out these events, as well as the trusting rapport between black Bishop and white office staffer Leigh (Laurie Zimmer)—who soon comes to share unspoken but palpable chemistry with Wilson—with great economy. Assault On Precinct 13’s shootouts boast a swift, gripping brutality, despite the fact that the swarming Street Thunder members who lay siege to the station exhibit an idiotic penchant for barreling headfirst through doorways and windows, thus making them easy targets.

Tension is amplified by the social and racial undercurrents that course throughout the film. Be it Bishop and Leigh’s early back-and-forth about a cup of coffee, the interracial makeup of Street Thunder (made up of whites, blacks, and Latinos), or the uneasy alliance between Bishop and Wilson, Assault On Precinct 13 steeps its action in a volatile multicultural stew. That mix is made even more explosive by the gender/sex issue of Leigh’s participation in the precinct’s defense—a thread that’s amusingly dramatized by her defusing a convict’s panic by grabbing the barrel of his gun and finding it unloaded.

Slant: It’s easy to dismiss the film’s racial morality play as simple, but there’s plenty going on beneath the surface of Carpenter’s formalist exercise. At Precinct 13, Carpenter envisions a society in moral transition. A crazed and naïve Kathy can’t understand why anyone would shoot at a police station (observe the startling defiance of authority when gang members walk stealthily toward the police station with “DO NOT ENTER” street signs to either side of them), and when she realizes that Street Thunder is only after the traumatized man who ran into the Precinct, she suggests that they throw him back into the street. “Don’t give me that civilized look!” she screams, feeling the burn of Bishop and Leigh’s scorn. With a name like Bishop, it’s not surprising that Stoker’s hero is a man of God who is not about to forsake his fellow man much-needed sanctuary.

Because Assault on Precinct 13 is among one of the most remarkably composed films of all time, it’s easy to look at Carpenter’s rigorous framing techniques as their own acts of political resistance. The film’s tight medium-shots position the characters in constant defiance of each other: blacks against whites, women against men, prisoners against officers. When Wells announces that he will attempt to escape Precinct 13 (he humorously calls his plan “Save Ass”), Bishop suggests a fairer approach. After a speedy lesson in trust and human decency, Wells and Wilson engage in a quickie game of Potatoes that positions Wells as the group’s potential gateway out of the police station. Despite the tragic but inevitable human losses, no one group comes out on top because only their capacity for kindness reigns supreme in Carpenter’s democratic kingdom.

The Dissolve: The gang in The Assault On Precinct 13 is a lot like masked murderer Michael Myers, the star of Carpenter’s slasher-film follow-up, 1978’s Halloween. They are a force of overwhelming and conscienceless evil. Carpenter doesn’t psychoanalyze his heavies. Like everyone else in Carpenter’s existential universe, the bad guys are defined not by their words or emotions, but by their actions and their unrelenting, uncompromising aggression.

From the very beginning, Carpenter was a genius at making a little go a long way, both in terms of resources and dialogue. Napoleon doesn’t say much beyond asking for a smoke with such dogged frequency, it quickly becomes his catchphrase. He doesn’t have to. Joston can do more with a wry look than most actors can do with lengthy monologues. Like Kurt Russell, who became Carpenter’s favorite actor, Joston understood that less is more, and that coolness requires an effortlessness that cannot be faked. Yet as impressive as Stoker and Joston are, they’re upstaged throughout by Laurie Zimmer as Leigh, a police secretary who evolves into a sexy badass in a time of crisis.

Carpenter intermittently cuts to shots of police officers in patrol cars in the area, trying to figure out what’s happened to the police station and why its phone lines have gone dead, but otherwise, the film boasts an claustrophobic intensity that puts audiences in the besieged police station alongside its overmatched but determined protagonists. In Assault On Precinct 13, hell is an abandoned police station in Los Angeles and the only means of survival is cooperation across racial, class, and legal lines. In combining the dread and survival politics of George Romero and The Night Of The Living Dead with the macho heroics and succinct wit of Howard Hawks, Carpenter found his own voice and changed the course of genre filmmaking.

Trailer

Ice cream

John Carpenter’s cult gang-siege flick made sunny Southern California scary

Anatomy Of A Soundtrack | John Carpenter’s Assault On Precinct 13 (1976)

Celebrating John Carpenter's Assault On Precinct 13

Deadspin: John Carpenter’s original Assault on Precinct 13 is one of the greatest zombie movies of all time, and there’s not a single zombie in it. The elements are all there: The chilling synth score, a cast of randoms thrown together by chance, an isolated siege site, the narrow escapes and eerie moments before all hell breaks loose, the characters dropping like flies and battling an overwhelming numbers of enemies, the scenes where our heroes hopelessly try to block off the entrances, and the scenes where the bad guys finally break through. But instead of actually making a zombie movie —something that barely existed in 1976, when the movie came out— Carpenter used those zombie movie techniques to tell a story about wayward gang youth, a pretty mundane subject in the hands of just about any other director.

AV Club: John Carpenter uses Rio Bravo as the template for his 1976 sophomore directorial effort Assault On Precinct 13, a neo-Western about a police station under attack from a Los Angeles gang known as Street Thunder. That barrage is motivated by a series of events that Carpenter stages with mounting tension, and suggests a world ensnared in a ceaseless cycle of slaughter. In response to faceless cops murdering their comrades, gang members go on the prowl, looking to retaliate against innocent bystanders. They eventually settle on an ice-cream truck driver and—in an infamous, still-shocking scene—a young girl, whose fatal bullet to the chest is filmed straight on, fully establishing Street Thunder’s (and the film’s) ruthlessness.

Violence begets violence in Assault On Precinct 13, as the father of the slain girl guns down her killer, and then flees to a precinct in slummy Anderson, California, that’s in the process of being shut down (hence few weapons or staffers), and under the command of newly assigned Lieutenant Bishop (Austin Stoker). Complicating matters further, a trio of convicts, on its way to another prison, has made a pit stop at Precinct 13. They’re led by Napoleon Wilson (Darwin Joston), a cocky, wisecracking criminal whose recurring requests for cigarettes and refusal to explain the origins of his first name provide a strain of smart-ass humor.

Carpenter’s script lays out these events, as well as the trusting rapport between black Bishop and white office staffer Leigh (Laurie Zimmer)—who soon comes to share unspoken but palpable chemistry with Wilson—with great economy. Assault On Precinct 13’s shootouts boast a swift, gripping brutality, despite the fact that the swarming Street Thunder members who lay siege to the station exhibit an idiotic penchant for barreling headfirst through doorways and windows, thus making them easy targets.

Tension is amplified by the social and racial undercurrents that course throughout the film. Be it Bishop and Leigh’s early back-and-forth about a cup of coffee, the interracial makeup of Street Thunder (made up of whites, blacks, and Latinos), or the uneasy alliance between Bishop and Wilson, Assault On Precinct 13 steeps its action in a volatile multicultural stew. That mix is made even more explosive by the gender/sex issue of Leigh’s participation in the precinct’s defense—a thread that’s amusingly dramatized by her defusing a convict’s panic by grabbing the barrel of his gun and finding it unloaded.

Slant: It’s easy to dismiss the film’s racial morality play as simple, but there’s plenty going on beneath the surface of Carpenter’s formalist exercise. At Precinct 13, Carpenter envisions a society in moral transition. A crazed and naïve Kathy can’t understand why anyone would shoot at a police station (observe the startling defiance of authority when gang members walk stealthily toward the police station with “DO NOT ENTER” street signs to either side of them), and when she realizes that Street Thunder is only after the traumatized man who ran into the Precinct, she suggests that they throw him back into the street. “Don’t give me that civilized look!” she screams, feeling the burn of Bishop and Leigh’s scorn. With a name like Bishop, it’s not surprising that Stoker’s hero is a man of God who is not about to forsake his fellow man much-needed sanctuary.

Because Assault on Precinct 13 is among one of the most remarkably composed films of all time, it’s easy to look at Carpenter’s rigorous framing techniques as their own acts of political resistance. The film’s tight medium-shots position the characters in constant defiance of each other: blacks against whites, women against men, prisoners against officers. When Wells announces that he will attempt to escape Precinct 13 (he humorously calls his plan “Save Ass”), Bishop suggests a fairer approach. After a speedy lesson in trust and human decency, Wells and Wilson engage in a quickie game of Potatoes that positions Wells as the group’s potential gateway out of the police station. Despite the tragic but inevitable human losses, no one group comes out on top because only their capacity for kindness reigns supreme in Carpenter’s democratic kingdom.

The Dissolve: The gang in The Assault On Precinct 13 is a lot like masked murderer Michael Myers, the star of Carpenter’s slasher-film follow-up, 1978’s Halloween. They are a force of overwhelming and conscienceless evil. Carpenter doesn’t psychoanalyze his heavies. Like everyone else in Carpenter’s existential universe, the bad guys are defined not by their words or emotions, but by their actions and their unrelenting, uncompromising aggression.

From the very beginning, Carpenter was a genius at making a little go a long way, both in terms of resources and dialogue. Napoleon doesn’t say much beyond asking for a smoke with such dogged frequency, it quickly becomes his catchphrase. He doesn’t have to. Joston can do more with a wry look than most actors can do with lengthy monologues. Like Kurt Russell, who became Carpenter’s favorite actor, Joston understood that less is more, and that coolness requires an effortlessness that cannot be faked. Yet as impressive as Stoker and Joston are, they’re upstaged throughout by Laurie Zimmer as Leigh, a police secretary who evolves into a sexy badass in a time of crisis.

Carpenter intermittently cuts to shots of police officers in patrol cars in the area, trying to figure out what’s happened to the police station and why its phone lines have gone dead, but otherwise, the film boasts an claustrophobic intensity that puts audiences in the besieged police station alongside its overmatched but determined protagonists. In Assault On Precinct 13, hell is an abandoned police station in Los Angeles and the only means of survival is cooperation across racial, class, and legal lines. In combining the dread and survival politics of George Romero and The Night Of The Living Dead with the macho heroics and succinct wit of Howard Hawks, Carpenter found his own voice and changed the course of genre filmmaking.

Trailer

Ice cream

John Carpenter’s cult gang-siege flick made sunny Southern California scary

Anatomy Of A Soundtrack | John Carpenter’s Assault On Precinct 13 (1976)

Celebrating John Carpenter's Assault On Precinct 13

I think it's missing a word on the intense, claustrophobic title theme, which ranks pretty high on my iconic title tracks list.

posted by lmfsilva at 6:37 AM on May 9, 2018

posted by lmfsilva at 6:37 AM on May 9, 2018

I rented this in college because Dark Star was rented already, and my roommate and I were casually watching and doing other things when we saw the little girl scene. After that we couldn't look away.

posted by infinitewindow at 1:52 PM on May 9, 2018

posted by infinitewindow at 1:52 PM on May 9, 2018

If you want a chaser for this, check out Brian O'Malley's Let Us Prey, which is like Assault on Precinct 13 crossed with Prince of Darkness.

You have my attention. Any idea where to stream it?

posted by DrAstroZoom at 7:50 AM on May 11, 2018

You have my attention. Any idea where to stream it?

posted by DrAstroZoom at 7:50 AM on May 11, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

If you want a chaser for this, check out Brian O'Malley's Let Us Prey, which is like Assault on Precinct 13 crossed with Prince of Darkness.

posted by DirtyOldTown at 6:14 AM on May 9, 2018