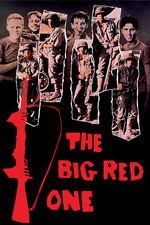

The Big Red One (1980)

March 19, 2016 11:03 AM - Subscribe

The story of a sergeant and the inner core members of his unit as they try to serve in and survive World War II. A semi-autobiographical account by director Samuel Fuller; the original version was chopped from a 270 minute cut to 113; most reviews below are from the 2004 "Reconstruction" version which, although it post-dated Fuller's death, likely comes closer to realizing his vision.

Slant: Uninterested in the larger politics and military strategy of the continent-crossing conflict, Fuller instead concentrates on his characters and their specific, moment-to-moment experiences during skirmishes and downtime in order to capture the agony, joy, madness, and terror of battle. A stirring Omaha beach sequence (shot with stark coarseness by Adam Greenberg) intersperses the soldiers’ attempts to reach safety with shots of a dead man’s watch lying in the blood-red surf, vividly demonstrating the grueling, seemingly endless nature of the siege. Intense close-ups of the infantrymen’s eyes peeking ever-so-slightly out of a foxhole (an image first used by Fuller in 1951’s The Steel Helmet) capture the disbelief, dread, and hopelessness that regularly gripped the men’s hearts. More than any other WWII film, The Big Red One conveys the experience of being on the ground, on the run, and scared to death.

Roger Ebert: What we understand, finally, is that the entire war comes down to these five men, because it is their entire war. Nobody wades ashore with 10,000 men. They wade ashore all by themselves. By limiting the scope of the action, Fuller was able to make the movie look completely convincing on his limited budget, using Ireland for the scenes set in Belgium and Israel for all the other scenes. We see tanks and planes and Germans and landing craft when we need to, but the focus is on the faces of the squad members.

Talking with Fuller, I quoted Truffaut's dictum that all war movies are pro-war, because no matter what their "message" is, they make the action look exciting.

Fuller snorted. "Pro or anti, what the hell difference does it make to the guy who gets his ass shot off? The movie is very simple. It's a series of combat experiences, and the times of waiting in between. Lee Marvin plays a carpenter of death. The sergeants of this world have been dealing death to young men for 10,000 years. He's a symbol of all those years and all those sergeants, no matter what their names were or what they called their rank in other languages. That's why he has no name in the movie.

"The movie deals with death in a way that might be unfamiliar to people who know nothing of war except what they learned in war movies. I believe that fear doesn't delay death, and so it is fruitless. A guy is hit. So, he's hit. That's that. I don't cry because that guy over there got hit. I cry because I'm gonna get hit next. All that phony heroism is a bunch of baloney when they're shooting at you. But you have to be honest with a corpse, and that is the emotion that the movie shows rubbing off on four young men."

Yes, it does. And that's why Griff, the squad member who doesn't like killing, pumps 20 rounds into a Nazi in one of the final scenes. He is a killer, shooting at a murderer.

NY Times: As the soldiers trundle from one hair-raising battle to the next, pausing to take in the blasted scenery and human devastation that surrounds them, themes and motifs present themselves. You notice the repeated appearance of children, who are drawn to the taciturn Sergeant and who illuminate a tender side of his personality that he himself might not acknowledge. The narrative occasionally crosses over to the enemy side, to follow the progress of a German officer named Schroeder, who is the Sergeant's negative mirror image. Their similarities suggest that, in war, the distinction between heroism and villainy is so faint as to be nearly invisible.

The moral of the story -- introduced as "fictional life based on factual death" -- is that "the only glory in war is surviving." In both of these statements, the emphasis falls, almost in spite of itself, on life. And "The Big Red One," for all its uncompromising brutality, is viscerally, angrily alive. Fuller was lucky to survive the war. It is our good fortune that this film, a tribute to his luck (and to those who did not share it), has come back to life.

AV Club: In some respects a less tidy film than before, particularly when it veers off into a subplot involving a Nazi soldier played by Siegfried Rauch, the new cut mostly retains the original's virtues while adding details and episodes that make it more recognizably a Fuller film. Often a source of accusing innocence in the director's work, children play a more prominent role here. Carradine now has a scene in which he makes elaborate plans to honor a fallen squad-mate by fulfilling an unusual sexual fantasy. More screen time gives Marvin, in one of his finest performances, greater room to bring out the subtle gradations of his stone face. Fuller himself even shows up in a cameo, playing a filmmaker trying to capture the details before they slip away as he chums it up with the troops. His two-minute scene sums up a career that took him from journalist to filmmaker to raconteur. And now it appears in a film that looks more than ever like the valediction Fuller always intended.

Senses of Cinema: A litany that consumes most of the film in various permutations is “We don’t murder, we kill”, a soldier’s justification. Toward the end, the balance shifts. The male family which has developed through the film, The Paternal Sergeant, and the four privates, begins to be predicated on the survival of this core within the larger group of the squad – as they survive each battle, they begin believe/hope for their invincibility. They begin to exclude other members of the squad (“replacements”, regarded as new, and so not part of the original group) and also expendable, not worth getting to know. The film moves toward a conclusion based on the idea of survival: us, the enemy, civilians, all the same: the only victory in war is surviving.

Fuller had wanted Lee Marvin for his Sergeant since the project began to be proposed, and had promised him the part. Like Fuller, Marvin had seen World War II combat (in the Pacific with the Marines, and had suffered considerable battle trauma). Marvin’s controlled, down-played work in the film is remarkable: his athleticism in his mid-50s; his easy familiarity with all things military; his purring, cottony voice, almost never raised, always laconic; his lined and seamed saurian face, and the eyes which miss nothing. Quite a team, these two vets, Marvin and Fuller.

Salon: Marvin will never be classed with Brando or Olivier. He didn’t have the range or the ferocity. But as the American infantry sergeant shepherding a group of “dogfaces” through combat in the European theater during World War II, Marvin gives the kind of performance that is the essence of movie acting.

He connects with the four young actors playing his platoon — Robert Carradine, Mark Hamill, Bobby Di Cicco and Kelly Ward — but he’s scaled his acting to the camera. Each gesture, each line reading, is precise, modest, on a pitch equal to the moment. Nothing sticks out — not even that trademark purring snarl; you never see him “acting.” But the smallest gradations of expression register large and clear on screen. Marvin is so convincing that by the end of “The Big Red One” you expect to encounter his face in a documentary or a book of photojournalism on the American soldiers who fought in World War II (as Marvin himself did, lying about his age to get into the Marines).

Cinephilia & Beyond: The Big Red One

Pulp Nonfiction and The Big Red One

Trailer

Slant: Uninterested in the larger politics and military strategy of the continent-crossing conflict, Fuller instead concentrates on his characters and their specific, moment-to-moment experiences during skirmishes and downtime in order to capture the agony, joy, madness, and terror of battle. A stirring Omaha beach sequence (shot with stark coarseness by Adam Greenberg) intersperses the soldiers’ attempts to reach safety with shots of a dead man’s watch lying in the blood-red surf, vividly demonstrating the grueling, seemingly endless nature of the siege. Intense close-ups of the infantrymen’s eyes peeking ever-so-slightly out of a foxhole (an image first used by Fuller in 1951’s The Steel Helmet) capture the disbelief, dread, and hopelessness that regularly gripped the men’s hearts. More than any other WWII film, The Big Red One conveys the experience of being on the ground, on the run, and scared to death.

Roger Ebert: What we understand, finally, is that the entire war comes down to these five men, because it is their entire war. Nobody wades ashore with 10,000 men. They wade ashore all by themselves. By limiting the scope of the action, Fuller was able to make the movie look completely convincing on his limited budget, using Ireland for the scenes set in Belgium and Israel for all the other scenes. We see tanks and planes and Germans and landing craft when we need to, but the focus is on the faces of the squad members.

Talking with Fuller, I quoted Truffaut's dictum that all war movies are pro-war, because no matter what their "message" is, they make the action look exciting.

Fuller snorted. "Pro or anti, what the hell difference does it make to the guy who gets his ass shot off? The movie is very simple. It's a series of combat experiences, and the times of waiting in between. Lee Marvin plays a carpenter of death. The sergeants of this world have been dealing death to young men for 10,000 years. He's a symbol of all those years and all those sergeants, no matter what their names were or what they called their rank in other languages. That's why he has no name in the movie.

"The movie deals with death in a way that might be unfamiliar to people who know nothing of war except what they learned in war movies. I believe that fear doesn't delay death, and so it is fruitless. A guy is hit. So, he's hit. That's that. I don't cry because that guy over there got hit. I cry because I'm gonna get hit next. All that phony heroism is a bunch of baloney when they're shooting at you. But you have to be honest with a corpse, and that is the emotion that the movie shows rubbing off on four young men."

Yes, it does. And that's why Griff, the squad member who doesn't like killing, pumps 20 rounds into a Nazi in one of the final scenes. He is a killer, shooting at a murderer.

NY Times: As the soldiers trundle from one hair-raising battle to the next, pausing to take in the blasted scenery and human devastation that surrounds them, themes and motifs present themselves. You notice the repeated appearance of children, who are drawn to the taciturn Sergeant and who illuminate a tender side of his personality that he himself might not acknowledge. The narrative occasionally crosses over to the enemy side, to follow the progress of a German officer named Schroeder, who is the Sergeant's negative mirror image. Their similarities suggest that, in war, the distinction between heroism and villainy is so faint as to be nearly invisible.

The moral of the story -- introduced as "fictional life based on factual death" -- is that "the only glory in war is surviving." In both of these statements, the emphasis falls, almost in spite of itself, on life. And "The Big Red One," for all its uncompromising brutality, is viscerally, angrily alive. Fuller was lucky to survive the war. It is our good fortune that this film, a tribute to his luck (and to those who did not share it), has come back to life.

AV Club: In some respects a less tidy film than before, particularly when it veers off into a subplot involving a Nazi soldier played by Siegfried Rauch, the new cut mostly retains the original's virtues while adding details and episodes that make it more recognizably a Fuller film. Often a source of accusing innocence in the director's work, children play a more prominent role here. Carradine now has a scene in which he makes elaborate plans to honor a fallen squad-mate by fulfilling an unusual sexual fantasy. More screen time gives Marvin, in one of his finest performances, greater room to bring out the subtle gradations of his stone face. Fuller himself even shows up in a cameo, playing a filmmaker trying to capture the details before they slip away as he chums it up with the troops. His two-minute scene sums up a career that took him from journalist to filmmaker to raconteur. And now it appears in a film that looks more than ever like the valediction Fuller always intended.

Senses of Cinema: A litany that consumes most of the film in various permutations is “We don’t murder, we kill”, a soldier’s justification. Toward the end, the balance shifts. The male family which has developed through the film, The Paternal Sergeant, and the four privates, begins to be predicated on the survival of this core within the larger group of the squad – as they survive each battle, they begin believe/hope for their invincibility. They begin to exclude other members of the squad (“replacements”, regarded as new, and so not part of the original group) and also expendable, not worth getting to know. The film moves toward a conclusion based on the idea of survival: us, the enemy, civilians, all the same: the only victory in war is surviving.

Fuller had wanted Lee Marvin for his Sergeant since the project began to be proposed, and had promised him the part. Like Fuller, Marvin had seen World War II combat (in the Pacific with the Marines, and had suffered considerable battle trauma). Marvin’s controlled, down-played work in the film is remarkable: his athleticism in his mid-50s; his easy familiarity with all things military; his purring, cottony voice, almost never raised, always laconic; his lined and seamed saurian face, and the eyes which miss nothing. Quite a team, these two vets, Marvin and Fuller.

Salon: Marvin will never be classed with Brando or Olivier. He didn’t have the range or the ferocity. But as the American infantry sergeant shepherding a group of “dogfaces” through combat in the European theater during World War II, Marvin gives the kind of performance that is the essence of movie acting.

He connects with the four young actors playing his platoon — Robert Carradine, Mark Hamill, Bobby Di Cicco and Kelly Ward — but he’s scaled his acting to the camera. Each gesture, each line reading, is precise, modest, on a pitch equal to the moment. Nothing sticks out — not even that trademark purring snarl; you never see him “acting.” But the smallest gradations of expression register large and clear on screen. Marvin is so convincing that by the end of “The Big Red One” you expect to encounter his face in a documentary or a book of photojournalism on the American soldiers who fought in World War II (as Marvin himself did, lying about his age to get into the Marines).

Cinephilia & Beyond: The Big Red One

Pulp Nonfiction and The Big Red One

Trailer

Cross of Iron would make nice companion viewing for this film. So would The Victors, I think, which I think of as possibly being all of the non combat war vignettes that could have happened in The Big Red One.

posted by MoonOrb at 11:30 AM on March 19, 2016

posted by MoonOrb at 11:30 AM on March 19, 2016

Fuller also wrote a companion novel to TBRO.

He lived near my grandparents when my dad was a kid ( Grampa sent him books from his store during wwii) and he and my uncle remember Fuller telling his war stories.

posted by brujita at 4:21 PM on March 20, 2016

He lived near my grandparents when my dad was a kid ( Grampa sent him books from his store during wwii) and he and my uncle remember Fuller telling his war stories.

posted by brujita at 4:21 PM on March 20, 2016

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

I think I saw this around the same time as seeing "Cross of Iron", and I think I liked that one a bit better? The two films have some similarities.

posted by selfnoise at 11:26 AM on March 19, 2016