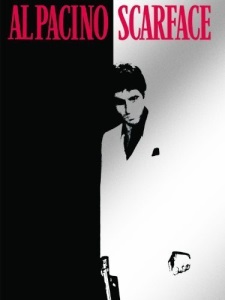

Scarface (1983)

April 25, 2018 6:05 PM - Subscribe

In Miami in 1980, a determined Cuban immigrant takes over a drug cartel and succumbs to greed.

Roger Ebert: The interesting thing is the way Tony Montana stays in the memory, taking on the dimensions of a real, tortured person. Most thrillers use interchangeable characters, and most gangster movies are more interested in action than personality, but "Scarface" is one of those special movies, like "The Godfather," that is willing to take a flawed, evil man and allow him to be human. Maybe it's no coincidence that Montana is played by Al Pacino, the same actor who played Michael Corleone.

NYTimes: I'm not at all sure what the film means to say about American business methods, though I suspect that Mr. De Palma and Mr. Stone would not be unhappy if it were seen as an ironic parable. For all his evil ways, Tony Montana, unlike some legitimate businessmen, always deals in first-class goods, though this may have less to do with his commitment to fair trade than with a desire to save his neck.

I also suspect that ''Scarface'' will be seen as something of an inside joke in Hollywood and other high-flying communities where cocaine is not regarded with the horror it is by this film. There is no other way to interpret the film's penultimate scene, in which Tony Montana sits in his throne room, his face buried in what appears to be at least $5 million worth of the controlled substance.

Yet the dominant mood of the film is anything but funny. It is bleak and futile: What goes up must always come down. When it comes down in ''Scarface,'' the crash is as terrifying as it is vivid and arresting.

Pauline Kael: De Palma may have felt that he could stretch himself by using a straightforward approach—something he has never been very good at. But what happens is simply that he’s stripped of his gifts. His originality doesn’t function on this crude, ritualized melodrama; he’s working against his own talent. In desperation, he seems to be trying to blast through the pulpy material to something primal, and it isn’t there. He keeps attempting to whip up big animalistic scenes, and then plods through them. And as the action rolls on, F. Murray Abraham is bumped off, and then Loggia (along with Harris Yulin, who turns up as a self-satisfied crooked narc and does perhaps the best work he’s ever done on the screen). And the piquant Michelle Pfeiffer—she hunches her beautiful skinny shoulder blades when she’s inhaling coke—doesn’t have enough disdainful, comic opportunities.

After a while, Pacino is a lump at the center of the movie. His Tony Montana has no bloom to lose, and he doesn’t suggest much in the way of potential: heights aren’t built into him. Nothing develops in Pacino’s performance. This is a two-hour-and-forty-nine-minute picture with a star whose imagination seems impaired. He wants to show us what an ignoramus this big-shot gangster is, and the role becomes an exercise in loathsomeness (on the order of De Niro’s performance in Raging Bull), without internal contradictions or shading. Pacino isn’t a lazy actor, and sometimes he comes up with invention that’s really inspired —like the way Tony, who’s all eyes for Elvira, bobs around her on the dance floor. It’s the only time he seems youthful: Elvira wriggles by herself, grinding her pelvis ever so slightly—this is her notion of sophisticated dancing—and he bounces about like a horny country bumpkin. (Pacino was also inspired in the contorted, ugly dancing he did in Cruising. ) But most of the time here he goes through the motions of impersonating a dynamo while looking as drained as he did at the end of The Godfather, Part II. He has no tension—his “dynamic” movements don’t connect to anything inside him. Then he gives up the fake energy, and this is supposed to stand for Tony’s disintegration. He’s doing the kind of Method acting in which the performer wants you to see that he’s living the part and expects you to be knocked out by his courage in running the gauntlet. Pacino is certainly willing to go all the way with Tony’s drunken and drugged-out loutishness. But he may be too comfortable with it; he’s sodden.

Empire: From his vile shirt to the zebra-skin Cadillac, to the shots of him face down scarfing a mountain of cocaine like a truffle-hog, Montana, like many of the gold-drenched rappers who have eulogised him, is revealed as a tasteless idiot. If he has any insight at all, it's the creeping one that this endless consumption is unlikely to finally satisfy, rendering happiness an impossibility.

However, to have one's film dismissed by the critics as, among other things, inept satire and then to see it adopted as iconic by the kind of people it condemns is surely some kind of perverse validation. That sound you can hear on the breeze might well be an uncharacteristically cheerful De Palma, cackling.

Slant: It’s ... surprising to think that this hugely popular and highly influential update of Howard Hawks’s classic Scarface met with howls of criticism when it was originally released. Remaking a Hawks film may have seemed sacrilegious at the time, but this Scarface remake is vastly superior to the majority of recent updates of classic films and TV shows. Instead of an actor, director, and screenwriter working on autopilot, Scarface has the impressive filmmaking triumvirate of De Palma, Stone, and Pacino. This combination of talent in front of and behind the camera must have had the executives at Universal eagerly anticipating another Godfather-style epic; a tasteful and sober examination of organised crime and the Miami cocaine business, and a film that would bring in big bucks and gain critical kudos. The result, though, wasn’t a subtle dissection of gangster life, but the equivalent of a bloodstained and bullet-riddled body, with De Palma and his crew ripping the guts out of the gangster movie and leaving the result on the operating table for all to see.

More Roger Ebert: "Scarface" is an example of Brian De Palma in overdrive mode. Like Tony Montana, he isn't interested in small gestures and subtle emotions. His best films are expansive, passionate, stylized and cheerfully excessive, and yet he has never caved in to the demand for routine action thrillers. Even his failures ("Snake Eyes") are at least ambitious. There is a mind at work in a De Palma picture, an idea behind the style, never a feeling of indifferent vulgarity. His most recent film, "Femme Fatale" (2002), was one of his best, an elegant and deceptive story based on the theft of a dress made of diamonds, which is stolen from the women wearing it during the opening night at the Cannes Film Festival. That the movie was not more successful is an indictment of the impatience of today's audiences, who want to be assaulted, not seduced.

A film like "Scarface" is more to their liking, which accounts for the film's enduring popularity, even in an edited-for-TV version that emasculates it. The movie has a headlong energy, hurtling toward its grand guignol climax. The cinematography, by the great John A. Alonzo, gloriously magnifies the icons in Tony's life -- the mansion, the toys, the lifestyle -- and then closes in on small, tight compositions as Tony's world shrinks.

Trailer

Streaming on Netflix

Documentary: The Making of Scarface (1983)

Why Scarface's critics were right the first time. It's awful

Revisiting the Controversy Surrounding Scarface

Watch: 36-Minute Discussion Of ‘Scarface’ With Al Pacino, Brian De Palma & Oliver Stone Plus 1983 Behind-The-Scenes Special

Michelle Pfeiffer Endures Bizarre Questions at Scarface Anniversary Event

Roger Ebert: The interesting thing is the way Tony Montana stays in the memory, taking on the dimensions of a real, tortured person. Most thrillers use interchangeable characters, and most gangster movies are more interested in action than personality, but "Scarface" is one of those special movies, like "The Godfather," that is willing to take a flawed, evil man and allow him to be human. Maybe it's no coincidence that Montana is played by Al Pacino, the same actor who played Michael Corleone.

NYTimes: I'm not at all sure what the film means to say about American business methods, though I suspect that Mr. De Palma and Mr. Stone would not be unhappy if it were seen as an ironic parable. For all his evil ways, Tony Montana, unlike some legitimate businessmen, always deals in first-class goods, though this may have less to do with his commitment to fair trade than with a desire to save his neck.

I also suspect that ''Scarface'' will be seen as something of an inside joke in Hollywood and other high-flying communities where cocaine is not regarded with the horror it is by this film. There is no other way to interpret the film's penultimate scene, in which Tony Montana sits in his throne room, his face buried in what appears to be at least $5 million worth of the controlled substance.

Yet the dominant mood of the film is anything but funny. It is bleak and futile: What goes up must always come down. When it comes down in ''Scarface,'' the crash is as terrifying as it is vivid and arresting.

Pauline Kael: De Palma may have felt that he could stretch himself by using a straightforward approach—something he has never been very good at. But what happens is simply that he’s stripped of his gifts. His originality doesn’t function on this crude, ritualized melodrama; he’s working against his own talent. In desperation, he seems to be trying to blast through the pulpy material to something primal, and it isn’t there. He keeps attempting to whip up big animalistic scenes, and then plods through them. And as the action rolls on, F. Murray Abraham is bumped off, and then Loggia (along with Harris Yulin, who turns up as a self-satisfied crooked narc and does perhaps the best work he’s ever done on the screen). And the piquant Michelle Pfeiffer—she hunches her beautiful skinny shoulder blades when she’s inhaling coke—doesn’t have enough disdainful, comic opportunities.

After a while, Pacino is a lump at the center of the movie. His Tony Montana has no bloom to lose, and he doesn’t suggest much in the way of potential: heights aren’t built into him. Nothing develops in Pacino’s performance. This is a two-hour-and-forty-nine-minute picture with a star whose imagination seems impaired. He wants to show us what an ignoramus this big-shot gangster is, and the role becomes an exercise in loathsomeness (on the order of De Niro’s performance in Raging Bull), without internal contradictions or shading. Pacino isn’t a lazy actor, and sometimes he comes up with invention that’s really inspired —like the way Tony, who’s all eyes for Elvira, bobs around her on the dance floor. It’s the only time he seems youthful: Elvira wriggles by herself, grinding her pelvis ever so slightly—this is her notion of sophisticated dancing—and he bounces about like a horny country bumpkin. (Pacino was also inspired in the contorted, ugly dancing he did in Cruising. ) But most of the time here he goes through the motions of impersonating a dynamo while looking as drained as he did at the end of The Godfather, Part II. He has no tension—his “dynamic” movements don’t connect to anything inside him. Then he gives up the fake energy, and this is supposed to stand for Tony’s disintegration. He’s doing the kind of Method acting in which the performer wants you to see that he’s living the part and expects you to be knocked out by his courage in running the gauntlet. Pacino is certainly willing to go all the way with Tony’s drunken and drugged-out loutishness. But he may be too comfortable with it; he’s sodden.

Empire: From his vile shirt to the zebra-skin Cadillac, to the shots of him face down scarfing a mountain of cocaine like a truffle-hog, Montana, like many of the gold-drenched rappers who have eulogised him, is revealed as a tasteless idiot. If he has any insight at all, it's the creeping one that this endless consumption is unlikely to finally satisfy, rendering happiness an impossibility.

However, to have one's film dismissed by the critics as, among other things, inept satire and then to see it adopted as iconic by the kind of people it condemns is surely some kind of perverse validation. That sound you can hear on the breeze might well be an uncharacteristically cheerful De Palma, cackling.

Slant: It’s ... surprising to think that this hugely popular and highly influential update of Howard Hawks’s classic Scarface met with howls of criticism when it was originally released. Remaking a Hawks film may have seemed sacrilegious at the time, but this Scarface remake is vastly superior to the majority of recent updates of classic films and TV shows. Instead of an actor, director, and screenwriter working on autopilot, Scarface has the impressive filmmaking triumvirate of De Palma, Stone, and Pacino. This combination of talent in front of and behind the camera must have had the executives at Universal eagerly anticipating another Godfather-style epic; a tasteful and sober examination of organised crime and the Miami cocaine business, and a film that would bring in big bucks and gain critical kudos. The result, though, wasn’t a subtle dissection of gangster life, but the equivalent of a bloodstained and bullet-riddled body, with De Palma and his crew ripping the guts out of the gangster movie and leaving the result on the operating table for all to see.

More Roger Ebert: "Scarface" is an example of Brian De Palma in overdrive mode. Like Tony Montana, he isn't interested in small gestures and subtle emotions. His best films are expansive, passionate, stylized and cheerfully excessive, and yet he has never caved in to the demand for routine action thrillers. Even his failures ("Snake Eyes") are at least ambitious. There is a mind at work in a De Palma picture, an idea behind the style, never a feeling of indifferent vulgarity. His most recent film, "Femme Fatale" (2002), was one of his best, an elegant and deceptive story based on the theft of a dress made of diamonds, which is stolen from the women wearing it during the opening night at the Cannes Film Festival. That the movie was not more successful is an indictment of the impatience of today's audiences, who want to be assaulted, not seduced.

A film like "Scarface" is more to their liking, which accounts for the film's enduring popularity, even in an edited-for-TV version that emasculates it. The movie has a headlong energy, hurtling toward its grand guignol climax. The cinematography, by the great John A. Alonzo, gloriously magnifies the icons in Tony's life -- the mansion, the toys, the lifestyle -- and then closes in on small, tight compositions as Tony's world shrinks.

Trailer

Streaming on Netflix

Documentary: The Making of Scarface (1983)

Why Scarface's critics were right the first time. It's awful

Revisiting the Controversy Surrounding Scarface

Watch: 36-Minute Discussion Of ‘Scarface’ With Al Pacino, Brian De Palma & Oliver Stone Plus 1983 Behind-The-Scenes Special

Michelle Pfeiffer Endures Bizarre Questions at Scarface Anniversary Event

I only actually saw this for the first time in the past 5 years or so, way after seeing it parodied in The Simpsons, and in fact I just recently had the inkling to see the 1932 Paul Muni version to compare. This movie just goes and goes.

I saw that Michelle Pfeiffer thing fly across the radar. No good deed goes un-dipshitted.

posted by rhizome at 7:17 PM on April 25, 2018

I saw that Michelle Pfeiffer thing fly across the radar. No good deed goes un-dipshitted.

posted by rhizome at 7:17 PM on April 25, 2018

It is absolutely beyond my ken why this picture's stock has continued to rise. I think it’s a disaster from start to finish.

posted by holborne at 10:09 PM on April 25, 2018

posted by holborne at 10:09 PM on April 25, 2018

While I have seen this film from start to finish, and found it relatively unremarkable, this film now holds sway in my mind due to a particular incident involving myself, my first child and the chainsaw scene.

When my youngest was a small baby, needing early morning feeds plus comfort, I was in the habit of having the TV on with low volume and sub titles. One evening, my little one had consumed his evening repast, and I was attempting to cuddle him off to sleep. As I did so, I was flicking idly through the channels, and happened to settle idly on Scarface. But not any scene in Scarface, the scene where Al Pacino is caught out of sorts in a hotel room and various chainsaw based mutilations occur.

It was at the exact moment that the chainsaw had started to whirr that my child decided that now was an excellent time to empty the entire contents of his stomach over myself, himself, and the sofa on which we were sitting.

My obvious immediate concern being my child, I patiently carried him over to the changing mat and begun to undress my child (who was beaming up at me, very pleased with himself). I proceeded to redress and clean him. Next of all, I did my best to clean the sofa. Finally, I dealt with myself. Despairing of cleaning my clothes, I simply chose to strip and wandered into the bedroom, nude, to pick up more clothes (briefly confusing my half asleep wife) and return to my perfectly happy trouble maker.

Throughout all of this, having not thought to switch off or even mute the television, this had been accompanied by the shrieks and sighs of a man being torn apart by a chainsaw.

posted by Cannon Fodder at 6:05 AM on April 26, 2018 [7 favorites]

When my youngest was a small baby, needing early morning feeds plus comfort, I was in the habit of having the TV on with low volume and sub titles. One evening, my little one had consumed his evening repast, and I was attempting to cuddle him off to sleep. As I did so, I was flicking idly through the channels, and happened to settle idly on Scarface. But not any scene in Scarface, the scene where Al Pacino is caught out of sorts in a hotel room and various chainsaw based mutilations occur.

It was at the exact moment that the chainsaw had started to whirr that my child decided that now was an excellent time to empty the entire contents of his stomach over myself, himself, and the sofa on which we were sitting.

My obvious immediate concern being my child, I patiently carried him over to the changing mat and begun to undress my child (who was beaming up at me, very pleased with himself). I proceeded to redress and clean him. Next of all, I did my best to clean the sofa. Finally, I dealt with myself. Despairing of cleaning my clothes, I simply chose to strip and wandered into the bedroom, nude, to pick up more clothes (briefly confusing my half asleep wife) and return to my perfectly happy trouble maker.

Throughout all of this, having not thought to switch off or even mute the television, this had been accompanied by the shrieks and sighs of a man being torn apart by a chainsaw.

posted by Cannon Fodder at 6:05 AM on April 26, 2018 [7 favorites]

It is absolutely beyond my ken why this picture's stock has continued to rise. I think it’s a disaster from start to finish.

I have to admit I never cared for the film, either. For me, it plays as just a huge, loud, almost satirical, mess, featuring an Italian-American over-playing-to-an-almost-insulting-degree a Cuban. I saw it when it came out and wasn’t impressed. I caught it again recently on tv and, boy howdy, it did not age well at all.

posted by Thorzdad at 1:50 PM on April 26, 2018 [2 favorites]

I have to admit I never cared for the film, either. For me, it plays as just a huge, loud, almost satirical, mess, featuring an Italian-American over-playing-to-an-almost-insulting-degree a Cuban. I saw it when it came out and wasn’t impressed. I caught it again recently on tv and, boy howdy, it did not age well at all.

posted by Thorzdad at 1:50 PM on April 26, 2018 [2 favorites]

huge, loud, almost satirical, mess

you say this as if it was a bad thing ...

posted by sapagan at 3:14 PM on March 20, 2020

you say this as if it was a bad thing ...

posted by sapagan at 3:14 PM on March 20, 2020

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Chrysostom at 7:11 PM on April 25, 2018 [3 favorites]