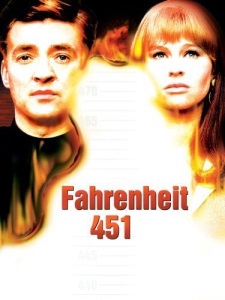

Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

June 15, 2018 6:53 PM - Subscribe

In an oppressive future, a fireman whose duty is to destroy all books begins to question his task.

Empire: Perhaps because it was his first film in English and he suffered a major falling-out with his Jules Et Jim star Oskar Werner during production, but Truffaut himself was never very fond of Fahrenheit 451. Most people who have written about it find it a hard movie to like, either because they feel the sci-fi elements let down Truffaut's humanist vision or because the director doesn't stick closely enough to Bradbury's. One piece of acute criticism came from George Bluestone, who noted that Truffaut could never quite work up the horror necessary to convey Bradbury's nightmare vision of a bibliophile society because, for him, the cinema was the sacred art/entertainment form.

He would have made a much more passionate film if the premise had been a world which banned and burned movies (we do glimpse Cahiers du Cinema and Chaplin's autobiography going up in flames along with Sartre, Nabokov, Dickens and MAD Magazine). Bradbury's novel, like George Orwell's similarly-plotted Nineteen Eighty-Four, is less a credible depiction of a future society than it is an allegorical satire on the present. This means that its points about McCarthyism or 1950s vulgarity are well-taken, but a film adaptation has to take seriously a story that never really tries to be credible. Clearly, a fascist society based on the suppression of books is a ridiculous premise — totalitarian governments take mass media over rather than take them away.

Why does everyone in this book-hating world learn to read? How does a book-hating fireman know the names of famous authors? What about songs or plays? Who writes the scripts for the banal soap operas? And how come it is so easy to leave the city and escape to join the rebels in the idyllic countryside? —- an influential non-ending followed by George Lucas' THX-1138, Blade Runner and the film of The Handmaid's Tale. Nevertheless, the film has a quiet creepiness that remains effective even though its future vision looks almost quaint now with its 1966 sparkliness (courtesy of cinematographer Nicolas Roeg).

The Dissolve: For people watching Fahrenheit 451 in 1966, a few fundamental problems are right there on the surface. Werner is terrible as Montag, the book-burning “fireman” of Bradbury’s totalitarian future. Julie Christie is nearly as bad in a dual role as Montag’s wife and a literate stranger. And Truffaut made serious alterations to the book, which offended those bent on fidelity to the classics. Nearly half a century later, Werner and Christie’s performances now seem like a less-fatal consequence of Truffaut working in a foreign language, and his interpretation of the book can be understood as more sophisticated than insolent, a thoughtful challenge to the text that nonetheless retains its spirit. Even Bradbury came around on it.

The most radical change was the one that met with Bradbury’s approval. In an oppressive society where books are outlawed and firemen carry hoses of kerosene instead of water, two women tug Montag’s conscience in opposite directions: his wife Linda (“Mildred” in the book), a sad woman who anesthetizes herself on pills and TV all day, and Clarisse, an ebullient stranger who prompts Montag to ask questions about why he does his job. Truffaut’s masterstroke was in casting Christie in both roles, and rendering the parts as the abstract representatives of conformity and non-conformity they had always been in the book. There’s no force other than their ideas—or the idea of them, anyway—that helps dictate the decisions Montag ultimately makes. They’re the opposite sides of the same coin.

The New Republic: Fahrenheit 451 is more interesting in the talking-over afterward than in the seeing. The movie is about a society in which books are forbidden, not censored or rewritten as in Orwell’s vision but simply forbidden, burned. Book-lovers run off to the woods where each memorizes a book and they become a living library. It is in the difference between the movie’s simple gimmick-idea and Orwell’s approach to censorship as an integral part of totalitarianism that we can see some of the weakness of the idea. Stripped of the resonances of politics and predictions and cautions, stripped of all those other repressions and forms of regimentation which are associated with book-burning, the idea is shallow, it operates in a void. The strength of the idea is that in removing book-burning from any political context, in using it as an isolated fearful fancy, it turns into something both more primitive and superficially more sophisticated than a part of a familiar, and by now somewhat banal, political cautionary message.

Of course, a gimmicky approach to the emptiness of life without books cannot convey what books mean or what they’re for: homage to literature and wisdom cannot be paid through a trick short-cut to profundity; the skimpy science-fiction script cannot create characters or observation that would make us understand imaginatively what book deprivation might be like. Among the books burned are Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination and The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury, who also wrote the book of Fahrenheit 451. This decorative little conceit has the effect of making us more aware than ever of the coyness and emptiness and inadequacy of the central conceit. The idea that one of the book-people at the end might be devoting his life to preserving a text by Ray Bradbury (or No Orchids for Miss Blandish, which we also see in flames) is enough to turn the movie into comedy. The next step is to imagine all the jerks we’ve known and what they might give their lives to preserving—Anthony Adverse? Magnificent Obsession? The Robe? The Adventurers? Valley of the Dolls? We have only to think about it to realize how absurd the idea is. Why should a society burn all books on the basis that books make people think and so disturb them and make them unhappy? Most books don’t make people think, and print is not in itself a danger to totalitarianism. That is a crotchety little librarian’s view of books. Print is as neutral as the television screen. And so we’re back from the primitive appeal of the gimmick to the Orwell vision of censorship and terror.

Trailer

Art of the Title

Fahrenheit 451: Reading the Film

Empire: Perhaps because it was his first film in English and he suffered a major falling-out with his Jules Et Jim star Oskar Werner during production, but Truffaut himself was never very fond of Fahrenheit 451. Most people who have written about it find it a hard movie to like, either because they feel the sci-fi elements let down Truffaut's humanist vision or because the director doesn't stick closely enough to Bradbury's. One piece of acute criticism came from George Bluestone, who noted that Truffaut could never quite work up the horror necessary to convey Bradbury's nightmare vision of a bibliophile society because, for him, the cinema was the sacred art/entertainment form.

He would have made a much more passionate film if the premise had been a world which banned and burned movies (we do glimpse Cahiers du Cinema and Chaplin's autobiography going up in flames along with Sartre, Nabokov, Dickens and MAD Magazine). Bradbury's novel, like George Orwell's similarly-plotted Nineteen Eighty-Four, is less a credible depiction of a future society than it is an allegorical satire on the present. This means that its points about McCarthyism or 1950s vulgarity are well-taken, but a film adaptation has to take seriously a story that never really tries to be credible. Clearly, a fascist society based on the suppression of books is a ridiculous premise — totalitarian governments take mass media over rather than take them away.

Why does everyone in this book-hating world learn to read? How does a book-hating fireman know the names of famous authors? What about songs or plays? Who writes the scripts for the banal soap operas? And how come it is so easy to leave the city and escape to join the rebels in the idyllic countryside? —- an influential non-ending followed by George Lucas' THX-1138, Blade Runner and the film of The Handmaid's Tale. Nevertheless, the film has a quiet creepiness that remains effective even though its future vision looks almost quaint now with its 1966 sparkliness (courtesy of cinematographer Nicolas Roeg).

The Dissolve: For people watching Fahrenheit 451 in 1966, a few fundamental problems are right there on the surface. Werner is terrible as Montag, the book-burning “fireman” of Bradbury’s totalitarian future. Julie Christie is nearly as bad in a dual role as Montag’s wife and a literate stranger. And Truffaut made serious alterations to the book, which offended those bent on fidelity to the classics. Nearly half a century later, Werner and Christie’s performances now seem like a less-fatal consequence of Truffaut working in a foreign language, and his interpretation of the book can be understood as more sophisticated than insolent, a thoughtful challenge to the text that nonetheless retains its spirit. Even Bradbury came around on it.

The most radical change was the one that met with Bradbury’s approval. In an oppressive society where books are outlawed and firemen carry hoses of kerosene instead of water, two women tug Montag’s conscience in opposite directions: his wife Linda (“Mildred” in the book), a sad woman who anesthetizes herself on pills and TV all day, and Clarisse, an ebullient stranger who prompts Montag to ask questions about why he does his job. Truffaut’s masterstroke was in casting Christie in both roles, and rendering the parts as the abstract representatives of conformity and non-conformity they had always been in the book. There’s no force other than their ideas—or the idea of them, anyway—that helps dictate the decisions Montag ultimately makes. They’re the opposite sides of the same coin.

The New Republic: Fahrenheit 451 is more interesting in the talking-over afterward than in the seeing. The movie is about a society in which books are forbidden, not censored or rewritten as in Orwell’s vision but simply forbidden, burned. Book-lovers run off to the woods where each memorizes a book and they become a living library. It is in the difference between the movie’s simple gimmick-idea and Orwell’s approach to censorship as an integral part of totalitarianism that we can see some of the weakness of the idea. Stripped of the resonances of politics and predictions and cautions, stripped of all those other repressions and forms of regimentation which are associated with book-burning, the idea is shallow, it operates in a void. The strength of the idea is that in removing book-burning from any political context, in using it as an isolated fearful fancy, it turns into something both more primitive and superficially more sophisticated than a part of a familiar, and by now somewhat banal, political cautionary message.

Of course, a gimmicky approach to the emptiness of life without books cannot convey what books mean or what they’re for: homage to literature and wisdom cannot be paid through a trick short-cut to profundity; the skimpy science-fiction script cannot create characters or observation that would make us understand imaginatively what book deprivation might be like. Among the books burned are Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination and The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury, who also wrote the book of Fahrenheit 451. This decorative little conceit has the effect of making us more aware than ever of the coyness and emptiness and inadequacy of the central conceit. The idea that one of the book-people at the end might be devoting his life to preserving a text by Ray Bradbury (or No Orchids for Miss Blandish, which we also see in flames) is enough to turn the movie into comedy. The next step is to imagine all the jerks we’ve known and what they might give their lives to preserving—Anthony Adverse? Magnificent Obsession? The Robe? The Adventurers? Valley of the Dolls? We have only to think about it to realize how absurd the idea is. Why should a society burn all books on the basis that books make people think and so disturb them and make them unhappy? Most books don’t make people think, and print is not in itself a danger to totalitarianism. That is a crotchety little librarian’s view of books. Print is as neutral as the television screen. And so we’re back from the primitive appeal of the gimmick to the Orwell vision of censorship and terror.

Trailer

Art of the Title

Fahrenheit 451: Reading the Film

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

Something that immediately looks up-to-date now is the wallscreen, in Montag's house -- watching the film now, they sure got that right, so futuristicly big and flat in comparison to the CRTs of the day (although not the floor-to-ceiling version of the novel).

But the thing that makes this movie outstanding is the soundtrack, by Bernard Herrmann.

posted by Rash at 7:00 PM on May 8, 2022