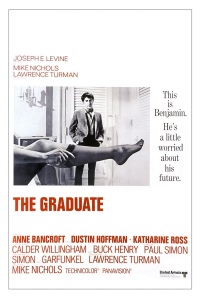

The Graduate (1967)

June 22, 2018 5:18 PM - Subscribe

A disillusioned college graduate finds himself torn between his older lover and her daughter.

AV Club: The Graduate, which joins the Criterion collection on Tuesday, isn’t an inspirational tale of young people overthrowing their parents’ materialistic, conformist attitudes in favor of freedom and true love—but then, it never was. The film’s magnificent cringe comedy derives from Benjamin’s utter cluelessness, which he never overcomes, even when he belatedly takes decisive action. Ebert’s description in his 1997 review is entirely accurate—his mistake was believing that his original, “Go Ben go!” reaction was what director Mike Nichols (working from a brilliant screenplay by Buck Henry and Calder Willingham) had intended, and that his more cynical response three decades later works against the movie’s grain. The Graduate has always been distinctly acid-tinged. That’s its particular and enduring genius.

That’s most apparent in Nichols’ revolutionary decision to cast Dustin Hoffman, who speaks at length in one of the Criterion edition’s supplementary interviews about his conviction that he was completely wrong for the part. (Nichols also discusses the subject with Steven Soderbergh on one of the disc’s two audio commentaries.) In Charles Webb’s 1963 source novel, Benjamin is the epitome of the WASP jock; the obvious choice for the role was the young Robert Redford, who reportedly lobbied for it. Instead, Nicholas chose the somewhat nerdy Hoffman, who created a performance that’s somehow robotic and intensely neurotic at the same time. Utterly adrift in the opening scenes, during which he’s assailed on all sides by adults demanding answers about his future, Ben becomes easy prey for Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), a family friend many years his senior (though Bancroft was in fact only six years older than Hoffman, playing a recent college grad at age 29). Her seduction, which runs over multiple scenes, remains one of Hollywood’s most glorious extended comic duets, with Mrs. Robinson’s sangfroid in hilariously direct proportion to Benjamin’s flustered anxiety.

Roger Ebert: Well, here *is* to you, Mrs. Robinson: You've survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in "The Graduate.'' How could I ever have thought otherwise? What murky generational politics were distorting my view the first time I saw this film? Watching the 30th anniversary revival of "The Graduate'' is like looking at photos of yourself at an old fraternity dance. You're gawky and your hair is plastered down with Brylcreem, and your date looks as if you found her behind the counter at the Dairy Queen. But--who's the babe in the corner? The great-looking brunette with the wide-set eyes and the full lips and the knockout figure? Hey, it's the chaperone! Great movies remain themselves over the generations; they retain a serene sense of their own identity. Lesser movies are captives of their time. They get dated and lose their original focus and power. "The Graduate'' (I can see clearly now) is a lesser movie. It comes out of a specific time in the late 1960s when parents stood for stodgy middle-class values, and "the kids'' were joyous rebels at the cutting edge of the sexual and political revolutions. Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), the clueless hero of "The Graduate,'' was swept in on that wave of feeling, even though it is clear today that he was utterly unaware of his generation and existed outside time and space (he seems most at home at the bottom of a swimming pool).

Empire: Nichols first approached an ageing Doris Day for the part of Mrs. Robinson, but she was horrified by the subject matter, terrified of ruffling her clean-cut 50s persona. Still, it is hard to imagine anyone but Anne Bancroft in the role. In reality merely seven years Hoffman's senior, she locates the dark heart of a character consumed by self-loathing and armoured in cool cynicism. She shifts from tragic to malicious, certainly a vampiric figure but in the face of the buttoned-down platitudes of their suffocating suburban deadzone her bitterness makes her real. She represents a Benjamin or Elaine (Ross) that has given in ("It's too late," she growls at a fleeing Elaine. "Not for me!" her daughter cruelly returns).

Hoffman was also a second choice. Nichols had mulled over Robert Redford as Benjamin but surmised that playing a bit of a loser would be a stretch for an actor that beautiful. In a career defining turn, Hoffman (then I 29), filled the angsty loafer with ; a nasally self-absorption, equally misfit and arsehole. Katharine Ross was blessed with the ideal American sweetheart looks for Elaine — the counterpoint to all the vulgar goings-on at the Taft Hotel. As the film shifts into its more romanticised second-half, Elaine is transformed into an elusive, angelic figure — another symbol of rescue for the hangdog loner Benjamin.

Slant: Nichols and veteran cinematographer Robert Surtees threw out the DGA playbook for The Graduate, experimenting wildly with lighting and lenses, lending the film a sense of freewheeling freshness, a sheen of visual inventiveness that hasn’t dimmed over the years. Handheld shots, exceedingly rare in those locked-down days, convey the obnoxious flesh-press of Benjamin’s graduation party, as well as the frenetic chaos of the climactic wedding chapel fray. In the opening scenes, Benjamin is consistently framed in angsty isolation against blank backgrounds—white voids in the plane and airport, the watery azures of fish tank and swimming pool—using the widescreen Panavision frame to pin him in place like an entomologist’s latest specimen.

Nichols and Surtees avail themselves of the format’s sprawling horizontality for telling deep-focus, multi-character compositions like the one that positions Ben and Mrs. Robinson at the extreme edges of the shot, embodying the emotional distance that separates them. When Ben reveals the secret of his clandestine affair to Elaine, the camera discovers a rain-drenched Mrs. Robinson in the doorway behind her, racking slowly from mother to daughter as the truth dawns on Elaine. After Elaine throws Ben out, there’s a cut to Mrs. Robinson, the camera slowly zooming out from her exultant face to discover her figure huddled in a corner, black widow’s weeds in startling contrast to the all-white décor, ending on Ben as he unhurriedly turns to the camera and the shot gradually fades to black, a virtual portmanteau of cinematic effects.

Nichols did things with sound that were pretty unconventional too, like using preexistent pop music to convey mood and texture. Granted, that’s something done to death over ensuing decades, but almost never with the same generosity; nowadays, a steady barrage of soundtrack-friendly hits cue emotional response with overweening Pavlovian precision. Nichols gives the music room to speak for the characters, letting Simon and Garfunkel’s folksy songs play out in their entirety as they alter the atmosphere from the satiric brio of “Mrs. Robinson” to the lovelorn lament of “Scarborough Fair.” Nichols and editor Sam O’Steen often use the music to shape their montages as in a sequence that equates Ben’s growing boredom with his parents’ idle chatter and his affectless affair with Mrs. Robinson, leading up to an outrageous match cut between Ben emerging from the pool and leaping onto his raft to a shot of him landing atop Mrs. Robinson.

Senses of Cinema: What is striking about The Graduate is how keenly it capitalises on the changes that characterised America in 1967. At least within the context of the Hollywood film industry, the film challenges some of the very basics of film storytelling and representation. With greater access to foreign cinema following the landmark Paramount Decree in 1948, which opened up the American exhibition spaces to both domestic and international cinema, The Graduate offers its own American spin on European art cinema. Historically, American cinema had been classical in its storytelling, its characters propelled by transparent goals; it was a cinema with objectives. But Nichols sets up Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) in defiance of these expectations; indeed, the first image we have of Ben is of him standing blankly on a travellator at the airport, propelled forward not by will, but by machine. And with that one extended image, Nichols perfectly crystallises the concerns of the film, and the cultural moment it represents. This is a film about movement and propulsion, the conveyor belt of social expectations, the milestones of acquisition and advancement. But it’s also about paralysis, indolence, a total absence of initiative.

Braddock, either by design or chance, comes in 1967 to symbolise both the expectations of a culture, and the youthful rejection of an aspirational capitalism that had shaped the previous generation. His concerns over his future are legitimate and real, but to reject the path mapped out for him due to his education and social class means there is no other path for him to follow. Despite the enticing intonation of the word “plastics”, Braddock is a man without industry. Nichols challenges the classical system by proposing a hero that lacks purpose, who exhibits as Thomas Elsaesser suggests “an almost physical sense of inconsequential action, of pointlessness and uselessness: stances which are not only interpretable psychologically, but speak of a radical scepticism about American values of ambition, vision, drive." Much like the characters in films from Michelangelo Antonioni or Jean-Luc Godard or Jacques Rivette, The Graduate disengages from typical quest narrative structures, and moves – at least for the first two-thirds of the film – towards a purely situational structure.

Trailer

At 50, The Graduate holds up. Its central character doesn't fare quite as well.

Here’s to You, Mr. Nichols: The Making of The Graduate

Commentary from the era of release: The Hollywood Reporter; Variety; Roger Ebert; The New Yorker

AV Club: The Graduate, which joins the Criterion collection on Tuesday, isn’t an inspirational tale of young people overthrowing their parents’ materialistic, conformist attitudes in favor of freedom and true love—but then, it never was. The film’s magnificent cringe comedy derives from Benjamin’s utter cluelessness, which he never overcomes, even when he belatedly takes decisive action. Ebert’s description in his 1997 review is entirely accurate—his mistake was believing that his original, “Go Ben go!” reaction was what director Mike Nichols (working from a brilliant screenplay by Buck Henry and Calder Willingham) had intended, and that his more cynical response three decades later works against the movie’s grain. The Graduate has always been distinctly acid-tinged. That’s its particular and enduring genius.

That’s most apparent in Nichols’ revolutionary decision to cast Dustin Hoffman, who speaks at length in one of the Criterion edition’s supplementary interviews about his conviction that he was completely wrong for the part. (Nichols also discusses the subject with Steven Soderbergh on one of the disc’s two audio commentaries.) In Charles Webb’s 1963 source novel, Benjamin is the epitome of the WASP jock; the obvious choice for the role was the young Robert Redford, who reportedly lobbied for it. Instead, Nicholas chose the somewhat nerdy Hoffman, who created a performance that’s somehow robotic and intensely neurotic at the same time. Utterly adrift in the opening scenes, during which he’s assailed on all sides by adults demanding answers about his future, Ben becomes easy prey for Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), a family friend many years his senior (though Bancroft was in fact only six years older than Hoffman, playing a recent college grad at age 29). Her seduction, which runs over multiple scenes, remains one of Hollywood’s most glorious extended comic duets, with Mrs. Robinson’s sangfroid in hilariously direct proportion to Benjamin’s flustered anxiety.

Roger Ebert: Well, here *is* to you, Mrs. Robinson: You've survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in "The Graduate.'' How could I ever have thought otherwise? What murky generational politics were distorting my view the first time I saw this film? Watching the 30th anniversary revival of "The Graduate'' is like looking at photos of yourself at an old fraternity dance. You're gawky and your hair is plastered down with Brylcreem, and your date looks as if you found her behind the counter at the Dairy Queen. But--who's the babe in the corner? The great-looking brunette with the wide-set eyes and the full lips and the knockout figure? Hey, it's the chaperone! Great movies remain themselves over the generations; they retain a serene sense of their own identity. Lesser movies are captives of their time. They get dated and lose their original focus and power. "The Graduate'' (I can see clearly now) is a lesser movie. It comes out of a specific time in the late 1960s when parents stood for stodgy middle-class values, and "the kids'' were joyous rebels at the cutting edge of the sexual and political revolutions. Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), the clueless hero of "The Graduate,'' was swept in on that wave of feeling, even though it is clear today that he was utterly unaware of his generation and existed outside time and space (he seems most at home at the bottom of a swimming pool).

Empire: Nichols first approached an ageing Doris Day for the part of Mrs. Robinson, but she was horrified by the subject matter, terrified of ruffling her clean-cut 50s persona. Still, it is hard to imagine anyone but Anne Bancroft in the role. In reality merely seven years Hoffman's senior, she locates the dark heart of a character consumed by self-loathing and armoured in cool cynicism. She shifts from tragic to malicious, certainly a vampiric figure but in the face of the buttoned-down platitudes of their suffocating suburban deadzone her bitterness makes her real. She represents a Benjamin or Elaine (Ross) that has given in ("It's too late," she growls at a fleeing Elaine. "Not for me!" her daughter cruelly returns).

Hoffman was also a second choice. Nichols had mulled over Robert Redford as Benjamin but surmised that playing a bit of a loser would be a stretch for an actor that beautiful. In a career defining turn, Hoffman (then I 29), filled the angsty loafer with ; a nasally self-absorption, equally misfit and arsehole. Katharine Ross was blessed with the ideal American sweetheart looks for Elaine — the counterpoint to all the vulgar goings-on at the Taft Hotel. As the film shifts into its more romanticised second-half, Elaine is transformed into an elusive, angelic figure — another symbol of rescue for the hangdog loner Benjamin.

Slant: Nichols and veteran cinematographer Robert Surtees threw out the DGA playbook for The Graduate, experimenting wildly with lighting and lenses, lending the film a sense of freewheeling freshness, a sheen of visual inventiveness that hasn’t dimmed over the years. Handheld shots, exceedingly rare in those locked-down days, convey the obnoxious flesh-press of Benjamin’s graduation party, as well as the frenetic chaos of the climactic wedding chapel fray. In the opening scenes, Benjamin is consistently framed in angsty isolation against blank backgrounds—white voids in the plane and airport, the watery azures of fish tank and swimming pool—using the widescreen Panavision frame to pin him in place like an entomologist’s latest specimen.

Nichols and Surtees avail themselves of the format’s sprawling horizontality for telling deep-focus, multi-character compositions like the one that positions Ben and Mrs. Robinson at the extreme edges of the shot, embodying the emotional distance that separates them. When Ben reveals the secret of his clandestine affair to Elaine, the camera discovers a rain-drenched Mrs. Robinson in the doorway behind her, racking slowly from mother to daughter as the truth dawns on Elaine. After Elaine throws Ben out, there’s a cut to Mrs. Robinson, the camera slowly zooming out from her exultant face to discover her figure huddled in a corner, black widow’s weeds in startling contrast to the all-white décor, ending on Ben as he unhurriedly turns to the camera and the shot gradually fades to black, a virtual portmanteau of cinematic effects.

Nichols did things with sound that were pretty unconventional too, like using preexistent pop music to convey mood and texture. Granted, that’s something done to death over ensuing decades, but almost never with the same generosity; nowadays, a steady barrage of soundtrack-friendly hits cue emotional response with overweening Pavlovian precision. Nichols gives the music room to speak for the characters, letting Simon and Garfunkel’s folksy songs play out in their entirety as they alter the atmosphere from the satiric brio of “Mrs. Robinson” to the lovelorn lament of “Scarborough Fair.” Nichols and editor Sam O’Steen often use the music to shape their montages as in a sequence that equates Ben’s growing boredom with his parents’ idle chatter and his affectless affair with Mrs. Robinson, leading up to an outrageous match cut between Ben emerging from the pool and leaping onto his raft to a shot of him landing atop Mrs. Robinson.

Senses of Cinema: What is striking about The Graduate is how keenly it capitalises on the changes that characterised America in 1967. At least within the context of the Hollywood film industry, the film challenges some of the very basics of film storytelling and representation. With greater access to foreign cinema following the landmark Paramount Decree in 1948, which opened up the American exhibition spaces to both domestic and international cinema, The Graduate offers its own American spin on European art cinema. Historically, American cinema had been classical in its storytelling, its characters propelled by transparent goals; it was a cinema with objectives. But Nichols sets up Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) in defiance of these expectations; indeed, the first image we have of Ben is of him standing blankly on a travellator at the airport, propelled forward not by will, but by machine. And with that one extended image, Nichols perfectly crystallises the concerns of the film, and the cultural moment it represents. This is a film about movement and propulsion, the conveyor belt of social expectations, the milestones of acquisition and advancement. But it’s also about paralysis, indolence, a total absence of initiative.

Braddock, either by design or chance, comes in 1967 to symbolise both the expectations of a culture, and the youthful rejection of an aspirational capitalism that had shaped the previous generation. His concerns over his future are legitimate and real, but to reject the path mapped out for him due to his education and social class means there is no other path for him to follow. Despite the enticing intonation of the word “plastics”, Braddock is a man without industry. Nichols challenges the classical system by proposing a hero that lacks purpose, who exhibits as Thomas Elsaesser suggests “an almost physical sense of inconsequential action, of pointlessness and uselessness: stances which are not only interpretable psychologically, but speak of a radical scepticism about American values of ambition, vision, drive." Much like the characters in films from Michelangelo Antonioni or Jean-Luc Godard or Jacques Rivette, The Graduate disengages from typical quest narrative structures, and moves – at least for the first two-thirds of the film – towards a purely situational structure.

Trailer

At 50, The Graduate holds up. Its central character doesn't fare quite as well.

Here’s to You, Mr. Nichols: The Making of The Graduate

Commentary from the era of release: The Hollywood Reporter; Variety; Roger Ebert; The New Yorker

I originally saw this as a teenager, sometime in the late 70s. I remember noticing the creative compositions of shots and becoming aware for the first time of the effect a director had on a film, that a film was more than acting and plot.

posted by bowline at 10:34 AM on June 23, 2018

posted by bowline at 10:34 AM on June 23, 2018

Well I mean he was Mel Brooks- he probably thought it was hilarious!

posted by Homo neanderthalensis at 2:36 PM on June 23, 2018

posted by Homo neanderthalensis at 2:36 PM on June 23, 2018

I watched the graduate twice before I drew the conclusion that I loathed the central character of Benjamin. I felt bad for Elaine and her mom. Elaine saddled with Benjamin and Mrs. Robinson in the wreckage of her personal and public life. I ended up being way more understanding of Mrs. Robinson's sadness of being invisible and Elaine's struggle against her mother with the dubious prize being Benjamin. So chalk me up as someone who separated out the obvious filmmaking talent from the story being told. I really admired the craft of the film but felt, at best, ambivalent about the story.

posted by jadepearl at 5:13 PM on June 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

posted by jadepearl at 5:13 PM on June 23, 2018 [6 favorites]

This is a brilliant movie highlighting the theme of alienation in the modern world that I would think holds true still, fifty years on.

It opens with a young Benjamin, recently graduated, and obviously confused, rudderless, dominated by family and its circumstance. Curious how the graduation party thrown on his behalf is handsomely attended... by nobody even close to his age. It's not clear that his own parents are even aware that the gathering is completely lacking in his peers. Benjamin himself seems less concerned about that than the void he faces in the time ahead. He appears nearly catatonic with uncertainty and dread, his only activity is squirming uncomfortably under the praise of one family friend after another, coming to a climax with Mrs. Robinson's pursuit in Elaine's bedroom. How it's all played out so humorously is remarkable, with Benjamin's sweaty evasiveness and cringeworthy awkwardness.

Mrs Robinson's gaslight-y pursuit of Benjamin appears to be the most aware and non-vacuous activity of the evening. She recognizes a similarly alienated soul, similarly not self anesthetized, a connection that Benjamin himself is too immature and disoriented to recognize immediately. She also seeks numbing. But not from a bottle.

The scene about half way through is just so heartbreaking and brilliant. Benjamin has moved to a point where he's eager to find some deeper meaning in his relationship with Mrs Robinson. While she's satisfied to continue without any such complication, and increasingly irritated at his probing, he manages to reluctantly draw out

the broken and abandoned dreams and regret she encountered. We see the battle scars she bears, the kind of scars Benjamin is too young and inexperienced and privileged to have earned. And a remarkable thing happens. Under Benjamin's queries, Mrs Robinson softens and opens up, the roles reverse, and Benjamin acknowledges that the tryst is the only bright spot in his life. And while the subject of Elaine is introduced as a pivot point in the story, we also see a softening of Mrs Robinson toward Benjamin, while Benjamin now insists they not complicate things further and continue on without talking. Robinson, for the first time smiling warmly, hangs her head in despair at being shut down, and proceeds to undress, her fate being that the fleeting comfort of their illicit affair is the best she can hope for.

Up to this point, Benjamin was the one being led around, Mrs Robinson in control of the activity, and of him. Her maturity and experience the driving and dominating force of the whole affair. At this scene, we find Mrs Robinson the one to yield, she needing the temporary companionship as much, if not more, than Benjamin. She gives up the Elaine card, and he now holds it before he ever meets up with her.

posted by 2N2222 at 3:21 PM on June 24, 2018 [2 favorites]

It opens with a young Benjamin, recently graduated, and obviously confused, rudderless, dominated by family and its circumstance. Curious how the graduation party thrown on his behalf is handsomely attended... by nobody even close to his age. It's not clear that his own parents are even aware that the gathering is completely lacking in his peers. Benjamin himself seems less concerned about that than the void he faces in the time ahead. He appears nearly catatonic with uncertainty and dread, his only activity is squirming uncomfortably under the praise of one family friend after another, coming to a climax with Mrs. Robinson's pursuit in Elaine's bedroom. How it's all played out so humorously is remarkable, with Benjamin's sweaty evasiveness and cringeworthy awkwardness.

Mrs Robinson's gaslight-y pursuit of Benjamin appears to be the most aware and non-vacuous activity of the evening. She recognizes a similarly alienated soul, similarly not self anesthetized, a connection that Benjamin himself is too immature and disoriented to recognize immediately. She also seeks numbing. But not from a bottle.

The scene about half way through is just so heartbreaking and brilliant. Benjamin has moved to a point where he's eager to find some deeper meaning in his relationship with Mrs Robinson. While she's satisfied to continue without any such complication, and increasingly irritated at his probing, he manages to reluctantly draw out

the broken and abandoned dreams and regret she encountered. We see the battle scars she bears, the kind of scars Benjamin is too young and inexperienced and privileged to have earned. And a remarkable thing happens. Under Benjamin's queries, Mrs Robinson softens and opens up, the roles reverse, and Benjamin acknowledges that the tryst is the only bright spot in his life. And while the subject of Elaine is introduced as a pivot point in the story, we also see a softening of Mrs Robinson toward Benjamin, while Benjamin now insists they not complicate things further and continue on without talking. Robinson, for the first time smiling warmly, hangs her head in despair at being shut down, and proceeds to undress, her fate being that the fleeting comfort of their illicit affair is the best she can hope for.

Up to this point, Benjamin was the one being led around, Mrs Robinson in control of the activity, and of him. Her maturity and experience the driving and dominating force of the whole affair. At this scene, we find Mrs Robinson the one to yield, she needing the temporary companionship as much, if not more, than Benjamin. She gives up the Elaine card, and he now holds it before he ever meets up with her.

posted by 2N2222 at 3:21 PM on June 24, 2018 [2 favorites]

"Ladies and gentlemen, we are about to make our decent into Los Angeles."

I hadn't seen this since the seventies and rewatched recently and was really blown away by it. I knew that it was a great drama but I didn't expect it to look and move so amazingly; the way that Penn and the cinematographer use the camera to tell the story is so powerful. The shot that The Slant article talks about is here and it's easily one of my top ten favorite shots in filmmaking. That slow focus on Elaine's face as she realizes what's going on is just so painfully perfect.

The only big problem I have with the film is the last act where I don't really buy a lot of the character motivations.

posted by octothorpe at 6:34 PM on June 24, 2018

I hadn't seen this since the seventies and rewatched recently and was really blown away by it. I knew that it was a great drama but I didn't expect it to look and move so amazingly; the way that Penn and the cinematographer use the camera to tell the story is so powerful. The shot that The Slant article talks about is here and it's easily one of my top ten favorite shots in filmmaking. That slow focus on Elaine's face as she realizes what's going on is just so painfully perfect.

The only big problem I have with the film is the last act where I don't really buy a lot of the character motivations.

posted by octothorpe at 6:34 PM on June 24, 2018

Elaine and Benjamin's motivations are indeed perplexing. Mrs. Robinson's motivations about Benjamin seeing Elaine are also a bit mystifying. None are explained, nor do they need to be, really. We can speculate, though. I think Mrs Robinson's go well beyond thinking Benjamin isn't good enough for her daughter. Perhaps she also wants to keep her little thing going. And her threat of scorched earth policy over Elaine feels like she very much wants to retain control of the relationship even as it slips from her grasp.

This control may also be a motivating factor for Elaine. She does end up in a church with Mr Perfect somewhat inexplicably, it seems that her parents had a significant hand in that turn of events. The way she busts out of there with the appearance of Benjamin's outrageous display suggests to me that she's not interested in being controlled any longer. Consequences be damned. She likes Benjamin OK. More than she likes having her future mapped out by her screwed up parents. The decision may be good, may be bad, but it's hers.

Benjamin's drive for the hand of Elaine feels more like obsession. He hardly knows her. But the desire for such a clear, seemingly unattainable, goal seems to be the thing to snap him out of the rut he'd been in. And as we see in the closing shots in the back of the bus, having succeeded, he once again faces that meaningless void. He rediscovers that wanting is often far more exciting than the having.

posted by 2N2222 at 11:03 PM on June 24, 2018 [1 favorite]

This control may also be a motivating factor for Elaine. She does end up in a church with Mr Perfect somewhat inexplicably, it seems that her parents had a significant hand in that turn of events. The way she busts out of there with the appearance of Benjamin's outrageous display suggests to me that she's not interested in being controlled any longer. Consequences be damned. She likes Benjamin OK. More than she likes having her future mapped out by her screwed up parents. The decision may be good, may be bad, but it's hers.

Benjamin's drive for the hand of Elaine feels more like obsession. He hardly knows her. But the desire for such a clear, seemingly unattainable, goal seems to be the thing to snap him out of the rut he'd been in. And as we see in the closing shots in the back of the bus, having succeeded, he once again faces that meaningless void. He rediscovers that wanting is often far more exciting than the having.

posted by 2N2222 at 11:03 PM on June 24, 2018 [1 favorite]

He rediscovers that wanting is often far more exciting than the having.

Great comment overall, I would perhaps just suggest it may be less about wanting and having than facing the void of an open future without controls to rebel against. What do you do after the rebellion when you've defined your choices by what you're against? How different is Benjamin than Mrs. Robinson in that sense? Why did she seek out an affair with Benjamin if not for rebellion? Elaine's choice in opposition to her mother seems reasonably clear, if not really developed, given her statement suggesting she's choosing an alternative to "settling", but will Benjamin provide a real alternative or is he, at the end, too still faced with a future without a better path; the void?

I don't think the movie really has clear answers to any of this, even some of the questions aren't fully realized, just suggested by the ending on the bus and the look on Benjamin's face. I'm not a big Nichols fan, but The Graduate really worked for me because it leaves so much hanging on his blank stare.

posted by gusottertrout at 12:16 AM on June 25, 2018 [2 favorites]

Great comment overall, I would perhaps just suggest it may be less about wanting and having than facing the void of an open future without controls to rebel against. What do you do after the rebellion when you've defined your choices by what you're against? How different is Benjamin than Mrs. Robinson in that sense? Why did she seek out an affair with Benjamin if not for rebellion? Elaine's choice in opposition to her mother seems reasonably clear, if not really developed, given her statement suggesting she's choosing an alternative to "settling", but will Benjamin provide a real alternative or is he, at the end, too still faced with a future without a better path; the void?

I don't think the movie really has clear answers to any of this, even some of the questions aren't fully realized, just suggested by the ending on the bus and the look on Benjamin's face. I'm not a big Nichols fan, but The Graduate really worked for me because it leaves so much hanging on his blank stare.

posted by gusottertrout at 12:16 AM on June 25, 2018 [2 favorites]

I saw this movie for the first time in the early-mid 70's in a high school film class. That shot of Elaine slowly coming into focus as she realizes the truth was the moment I suddenly understood how much the camera itself can tell the story. It was pretty revelatory to this then-teenager.

posted by Thorzdad at 7:41 AM on June 25, 2018 [1 favorite]

posted by Thorzdad at 7:41 AM on June 25, 2018 [1 favorite]

Saw this for the first time this evening at a local theater. Had skimmed this post first, and the six-year age difference between Bancroft and Hoffman stuck. Knowing that fact won me a free movie ticket!

Anyway, enjoyed it more than I thought I would. Trainwreck, but a funny trainwreck.

posted by asperity at 9:24 PM on July 24, 2019

Anyway, enjoyed it more than I thought I would. Trainwreck, but a funny trainwreck.

posted by asperity at 9:24 PM on July 24, 2019

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by sammyo at 7:18 PM on June 22, 2018 [4 favorites]