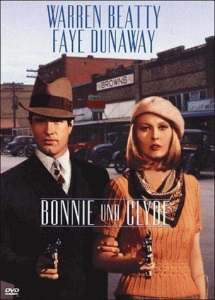

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

June 27, 2018 10:12 AM - Subscribe

Bonnie Parker, a bored waitress, falls in love with an ex-con named Clyde Barrow and together they start a violent crime spree through the country, stealing cars and robbing banks.

Pauline Kael, in the New Yorker: “Bonnie and Clyde” is the most excitingly American American movie since “The Manchurian Candidate.” The audience is alive to it. Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours—not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours. When an American movie is contemporary in feeling, like this one, it makes a different kind of contact with an American audience from the kind that is made by European films, however contemporary. Yet any movie that is contemporary in feeling is likely to go further than other movies—go too far for some tastes—and “Bonnie and Clyde” divides audiences, as “The Manchurian Candidate” did, and it is being jumped on almost as hard. Though we may dismiss the attacks with “What good movie doesn’t give some offense?,” the fact that it is generally only good movies that provoke attacks by many people suggests that the innocuousness of most of our movies is accepted with such complacence that when an American movie reaches people, when it makes them react, some of them think there must be something the matter with it—perhaps a law should be passed against it. “Bonnie and Clyde” brings into the almost frighteningly public world of movies things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about. And once something is said or done on the screens of the world, once it has entered mass art, it can never again belong to a minority, never again be the private possession of an educated, or “knowing,” group. But even for that group there is an excitement in hearing its own private thoughts expressed out loud and in seeing something of its own sensibility become part of our common culture.

The Hollywood Review: The dialogue is spare and tuned to the ear and the region. The ingenuity of the chases is superbly timed, building to peak hilarity and fading to blackouts. While the film was made on location throughout Texas in cities which have little change since the early thirties, the film sustains the documentary evocation of period one has long associated with Warner Brothers pictures. Penn manages to emphasize the relation of the story or legend to its time and place by excellent restatement of full and long shots. Again and again, his camera angles progress not into but away from the character action, placing it in perspective with the land.

Violent images are an important part of Penn’s directorial style, but his camera never lingers on gore. A fragmentary glimpse, sufficient to make the dramatically relevant impact, is enough. The same taste is evident in his handling of sex.

Roger Ebert: Under Arthur Penn's direction, this is a film aimed squarely and unforgivingly at the time we are living in. It is intended, horrifyingly, as entertainment. And so it will be taken. The kids on dates will go to see this one, just like they went to see "Dirty Dozen" and "Born Losers" and "Hells Angels on Wheels."

But this time, maybe, they'll get more than they counted on. The violence in most American movies is of a curiously bloodless quality. People are shot and they die, but they do not suffer. The murders are something to be gotten over with, so the audience will have its money's worth, the same is true of the sex. Both are like the toy in a Crackerjack box: Worthless, but you feel cheated it it's not there.

In "Bonnie and Clyde," however, real people die. Before they die they suffer, horribly. Before they suffer they laugh, and play checkers, and make love, or try to. These become people we know, and when they die it is not at all pleasant to be in the audience.

When people are shot in "Bonnie and Clyde." they are literally blown to bits. Perhaps that seems shocking. But perhaps at this time, it is useful to be reminded that bullets really do tear skin and bone, and that they don't make nice round little holes like the Swiss cheese effect in Fearless Fosdick.

We are living in a period when newscasts refer casually to "waves" of mass murders, Richard Speck's photograph is sold on posters in Old Town and snipers in Newark pose for Life magazine (perhaps they are busy now getting their ballads to rhyme). Violence takes on an unreal quality. The Barrow Gang reads its press clippings aloud for fun. When C.W. Moss takes the wounded Bonnie and Clyde to his father's home, the old man snorts: "What'd they ever do for you boy? Didn't even get your name in the paper." Is that a funny line, or a tragic one?

Slant: Stylistically, Arthur Penn’s crime epic doesn’t do anything that hadn’t already been seen in any number of runty, skuzzy teen epics, all of which firmly established the paragons of good (i.e. “The Law”) as being the new antagonists. More violent content had already been committed to film—admittedly not so often in Oscar-nominated blockbuster territory, but certainly in some of the films by Roger Corman and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Even the film’s beatsick emotional tone, treating death and destruction against a Dust Bowl backdrop previously defined by the works of John Steinbeck, was presaged by Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, which sort of bested everything that could’ve ever imaginably followed in the questionable-taste department by turning nuclear winter into humanity’s final glorious sunrise.

What Bonnie and Clyde added to this mix of preexisting ingredients was all but spelled out in the love-childish tagline: “They’re young. They’re in love. And they kill people.” So while Dub Taylor, Estelle Parsons, and a tightly-coiled Gene Wilder (in his movie debut) all carried on in service of the proud Paranoid Age tradition of Looney Tunes caricature (buttressed by that incessant bluegrass chase music), Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway pouted and sulked and looked all around fabulous at the center, resulting in an oddly self-absorbed bit of slapstick romantic fatalism, in every imaginable way a counterpart to the movie it most often gets lumped together with, The Graduate. (That Bonnie And Clyde couldn’t bridge the generation gap probably had a lot less to do with the film’s violence than it did the film’s seeming indifference to the class implications of the pair’s criminal acts.)

If Bonnie And Clyde‘s blood and guts seem a tad more digestible now than the watery pools, aquariums, and fountains of The Graduate, it could perhaps be because surface beauty and reckless violence committed with the name of retribution taken in vain are much closer to our current experience than a smug but excoriating dissection of the central soullessness of the American post-adolescent psyche. And though Bonnie And Clyde may have been conceived as a proto-European hybrid and The Graduate a California thoroughbred, the violent hemorrhage that closes the Depression-era/Vietnam-era touchstone makes as good a case as anything in filmed entertainment that American mass media operates in the declarative.

Vox: The kids loved Bonnie and Clyde, which became a rallying cry for the burgeoning counterculture. That might seem counterintuitive, since the characters at its center are based on some gangsters idolized in their parents’ and grandparents’ youth. But 1967 was a time for young people disillusioned with traditionalist culture to run hard in the opposite direction, gleefully flouting laws and norms about everything from drugs and sex to the “right” path in life. Bonnie and Clyde are an emblem of that attitude, and if they flame out in the end, boy, it’s sure romantic.

The romance of Bonnie and Clyde’s rebellion resonated in 1967 with young people who saw themselves — and their uncertain future in an age haunted by the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation — reflected onscreen. And every adaptation since then, whether it looked at the story through the lens of feminism, suburban critique, media criticism, or existential despair, has done the same. It’s deeply reflective of America in the past half-century — and we’ll almost certainly see the pair pop up onscreen again.

Empire: Naturally, the violence in Bonnie And Clyde was a sizeable bone of contention. But what really divided audiences was its moral ambiguity — its glamorising of two vicious killers and the easy manner in which it blended slapstick humour, overt eroticism and vivid bloodletting.

To the section of society that had choked on its collective martini over Guess Who's Coming To Dinner, it was the final nail in the coffin of common decency. To another, busy tuning in, turning in and dropping out, the anti-establishment image of two outlaw lovers on the run struck a resounding chord. The scene in which a cocksure Clyde offers his gun to a poor black sharecropper so he can shoot holes in the foreclosure sign erected by the bank that has evicted him, encapsulates the mood of the film perfectly. The criminal-as-folk-hero has been a theme intrinsic to American cinema ever since, and the Barrow gang's whole, dizzy crime spree is a defiant finger to the forces of law and order.

What distinguishes Bonnie And Clyde from the later slew of movies celebrating non-conformity — Easy Rider et al — is that alongside the life-affirming thrill they get from thumbing their noses at the law, both Bonnie and Clyde know that ultimately their fate is to die a violent death. This certainty haunts the film, and the moments where it bursts in on the gang's devil-may-care attitude are painful and sad.

Trailer

Filming locations

‘Bonnie and Clyde’ at 50: A Revolutionary Film That Now Looks Like the Last Work of Hollywood Classicism

They're young, they're in love, and they kill people: A look back at how Bonnie and Clyde revolutionized Hollywood

Bonnie and Clyde: The story of a scene

50 Years Later: How Bonnie and Clyde Violently Divided Film Critics

Bonnie And Clyde At 50: The Film’s Fashion Legacy

The Criterion Collection: Bonnie and Clyde at Fifty

Senses of Cinema: Riding the New Wave: The Case of Bonnie and Clyde

The Atlantic: Why Bonnie and Clyde Won't Die

NPR: The Real Story Of Bonnie And Clyde

Pauline Kael, in the New Yorker: “Bonnie and Clyde” is the most excitingly American American movie since “The Manchurian Candidate.” The audience is alive to it. Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours—not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours. When an American movie is contemporary in feeling, like this one, it makes a different kind of contact with an American audience from the kind that is made by European films, however contemporary. Yet any movie that is contemporary in feeling is likely to go further than other movies—go too far for some tastes—and “Bonnie and Clyde” divides audiences, as “The Manchurian Candidate” did, and it is being jumped on almost as hard. Though we may dismiss the attacks with “What good movie doesn’t give some offense?,” the fact that it is generally only good movies that provoke attacks by many people suggests that the innocuousness of most of our movies is accepted with such complacence that when an American movie reaches people, when it makes them react, some of them think there must be something the matter with it—perhaps a law should be passed against it. “Bonnie and Clyde” brings into the almost frighteningly public world of movies things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about. And once something is said or done on the screens of the world, once it has entered mass art, it can never again belong to a minority, never again be the private possession of an educated, or “knowing,” group. But even for that group there is an excitement in hearing its own private thoughts expressed out loud and in seeing something of its own sensibility become part of our common culture.

The Hollywood Review: The dialogue is spare and tuned to the ear and the region. The ingenuity of the chases is superbly timed, building to peak hilarity and fading to blackouts. While the film was made on location throughout Texas in cities which have little change since the early thirties, the film sustains the documentary evocation of period one has long associated with Warner Brothers pictures. Penn manages to emphasize the relation of the story or legend to its time and place by excellent restatement of full and long shots. Again and again, his camera angles progress not into but away from the character action, placing it in perspective with the land.

Violent images are an important part of Penn’s directorial style, but his camera never lingers on gore. A fragmentary glimpse, sufficient to make the dramatically relevant impact, is enough. The same taste is evident in his handling of sex.

Roger Ebert: Under Arthur Penn's direction, this is a film aimed squarely and unforgivingly at the time we are living in. It is intended, horrifyingly, as entertainment. And so it will be taken. The kids on dates will go to see this one, just like they went to see "Dirty Dozen" and "Born Losers" and "Hells Angels on Wheels."

But this time, maybe, they'll get more than they counted on. The violence in most American movies is of a curiously bloodless quality. People are shot and they die, but they do not suffer. The murders are something to be gotten over with, so the audience will have its money's worth, the same is true of the sex. Both are like the toy in a Crackerjack box: Worthless, but you feel cheated it it's not there.

In "Bonnie and Clyde," however, real people die. Before they die they suffer, horribly. Before they suffer they laugh, and play checkers, and make love, or try to. These become people we know, and when they die it is not at all pleasant to be in the audience.

When people are shot in "Bonnie and Clyde." they are literally blown to bits. Perhaps that seems shocking. But perhaps at this time, it is useful to be reminded that bullets really do tear skin and bone, and that they don't make nice round little holes like the Swiss cheese effect in Fearless Fosdick.

We are living in a period when newscasts refer casually to "waves" of mass murders, Richard Speck's photograph is sold on posters in Old Town and snipers in Newark pose for Life magazine (perhaps they are busy now getting their ballads to rhyme). Violence takes on an unreal quality. The Barrow Gang reads its press clippings aloud for fun. When C.W. Moss takes the wounded Bonnie and Clyde to his father's home, the old man snorts: "What'd they ever do for you boy? Didn't even get your name in the paper." Is that a funny line, or a tragic one?

Slant: Stylistically, Arthur Penn’s crime epic doesn’t do anything that hadn’t already been seen in any number of runty, skuzzy teen epics, all of which firmly established the paragons of good (i.e. “The Law”) as being the new antagonists. More violent content had already been committed to film—admittedly not so often in Oscar-nominated blockbuster territory, but certainly in some of the films by Roger Corman and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Even the film’s beatsick emotional tone, treating death and destruction against a Dust Bowl backdrop previously defined by the works of John Steinbeck, was presaged by Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, which sort of bested everything that could’ve ever imaginably followed in the questionable-taste department by turning nuclear winter into humanity’s final glorious sunrise.

What Bonnie and Clyde added to this mix of preexisting ingredients was all but spelled out in the love-childish tagline: “They’re young. They’re in love. And they kill people.” So while Dub Taylor, Estelle Parsons, and a tightly-coiled Gene Wilder (in his movie debut) all carried on in service of the proud Paranoid Age tradition of Looney Tunes caricature (buttressed by that incessant bluegrass chase music), Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway pouted and sulked and looked all around fabulous at the center, resulting in an oddly self-absorbed bit of slapstick romantic fatalism, in every imaginable way a counterpart to the movie it most often gets lumped together with, The Graduate. (That Bonnie And Clyde couldn’t bridge the generation gap probably had a lot less to do with the film’s violence than it did the film’s seeming indifference to the class implications of the pair’s criminal acts.)

If Bonnie And Clyde‘s blood and guts seem a tad more digestible now than the watery pools, aquariums, and fountains of The Graduate, it could perhaps be because surface beauty and reckless violence committed with the name of retribution taken in vain are much closer to our current experience than a smug but excoriating dissection of the central soullessness of the American post-adolescent psyche. And though Bonnie And Clyde may have been conceived as a proto-European hybrid and The Graduate a California thoroughbred, the violent hemorrhage that closes the Depression-era/Vietnam-era touchstone makes as good a case as anything in filmed entertainment that American mass media operates in the declarative.

Vox: The kids loved Bonnie and Clyde, which became a rallying cry for the burgeoning counterculture. That might seem counterintuitive, since the characters at its center are based on some gangsters idolized in their parents’ and grandparents’ youth. But 1967 was a time for young people disillusioned with traditionalist culture to run hard in the opposite direction, gleefully flouting laws and norms about everything from drugs and sex to the “right” path in life. Bonnie and Clyde are an emblem of that attitude, and if they flame out in the end, boy, it’s sure romantic.

The romance of Bonnie and Clyde’s rebellion resonated in 1967 with young people who saw themselves — and their uncertain future in an age haunted by the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation — reflected onscreen. And every adaptation since then, whether it looked at the story through the lens of feminism, suburban critique, media criticism, or existential despair, has done the same. It’s deeply reflective of America in the past half-century — and we’ll almost certainly see the pair pop up onscreen again.

Empire: Naturally, the violence in Bonnie And Clyde was a sizeable bone of contention. But what really divided audiences was its moral ambiguity — its glamorising of two vicious killers and the easy manner in which it blended slapstick humour, overt eroticism and vivid bloodletting.

To the section of society that had choked on its collective martini over Guess Who's Coming To Dinner, it was the final nail in the coffin of common decency. To another, busy tuning in, turning in and dropping out, the anti-establishment image of two outlaw lovers on the run struck a resounding chord. The scene in which a cocksure Clyde offers his gun to a poor black sharecropper so he can shoot holes in the foreclosure sign erected by the bank that has evicted him, encapsulates the mood of the film perfectly. The criminal-as-folk-hero has been a theme intrinsic to American cinema ever since, and the Barrow gang's whole, dizzy crime spree is a defiant finger to the forces of law and order.

What distinguishes Bonnie And Clyde from the later slew of movies celebrating non-conformity — Easy Rider et al — is that alongside the life-affirming thrill they get from thumbing their noses at the law, both Bonnie and Clyde know that ultimately their fate is to die a violent death. This certainty haunts the film, and the moments where it bursts in on the gang's devil-may-care attitude are painful and sad.

Trailer

Filming locations

‘Bonnie and Clyde’ at 50: A Revolutionary Film That Now Looks Like the Last Work of Hollywood Classicism

They're young, they're in love, and they kill people: A look back at how Bonnie and Clyde revolutionized Hollywood

Bonnie and Clyde: The story of a scene

50 Years Later: How Bonnie and Clyde Violently Divided Film Critics

Bonnie And Clyde At 50: The Film’s Fashion Legacy

The Criterion Collection: Bonnie and Clyde at Fifty

Senses of Cinema: Riding the New Wave: The Case of Bonnie and Clyde

The Atlantic: Why Bonnie and Clyde Won't Die

NPR: The Real Story Of Bonnie And Clyde

I lived in Dallas when this was made, and a couple of people I knew in high school were extras. Shortly after it came out, I discovered Bonnie Parker's grave with its reality-resistant epitaph (courtesy of her mother):

Note that, at age 26 when she made the movie, Faye Dunaway had already outlived Bonnie Parker by three years (Beatty had outlived Clyde by five).

posted by ubiquity at 8:40 AM on June 28, 2018

As The Flowers Are All Made SweeterEven today, 84 years later, the grave is continually covered in fresh flowers.

By The Sunshine And The Dew,

So This Old World Is Made Brighter

By The Lives Of Folks Like You.

Note that, at age 26 when she made the movie, Faye Dunaway had already outlived Bonnie Parker by three years (Beatty had outlived Clyde by five).

posted by ubiquity at 8:40 AM on June 28, 2018

But like a WEIRD amount of the movie is devoted to Warren Beatty's lack of confidence in the bedroom.

But this is part of what made the movie a breakthrough. Prior to B&C, a movie wanting to show the human side of an outlaw would have shown him taking in a kitten, or being kind to a child, or treating his girl or his mother gently and respectfully. B&C accepts that its protagonists are human, with human problems, and isn't afraid to portray those problems to further their characterizations.

posted by ubiquity at 10:16 AM on June 28, 2018 [2 favorites]

But this is part of what made the movie a breakthrough. Prior to B&C, a movie wanting to show the human side of an outlaw would have shown him taking in a kitten, or being kind to a child, or treating his girl or his mother gently and respectfully. B&C accepts that its protagonists are human, with human problems, and isn't afraid to portray those problems to further their characterizations.

posted by ubiquity at 10:16 AM on June 28, 2018 [2 favorites]

Don’t miss Gene Wilder’s big-screen debut!

posted by Thorzdad at 6:50 PM on June 28, 2018 [2 favorites]

posted by Thorzdad at 6:50 PM on June 28, 2018 [2 favorites]

This scene - such unexpectedly hysterical tone! It might be time for a rewatch.

What IS this movie???

posted by karmachameleon at 10:05 PM on July 1, 2018

What IS this movie???

posted by karmachameleon at 10:05 PM on July 1, 2018

Man, Faye Dunaway was in a lot of good stuff at her peak.

And then, later, in Supergirl.

posted by Chrysostom at 7:05 PM on July 8, 2018

And then, later, in Supergirl.

posted by Chrysostom at 7:05 PM on July 8, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by karmachameleon at 8:42 PM on June 27, 2018 [2 favorites]