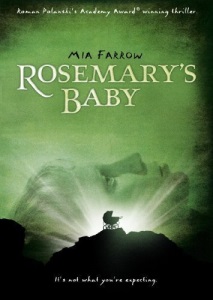

Rosemary's Baby (1968)

June 30, 2018 11:07 AM - Subscribe

A young couple moves in to an apartment only to be surrounded by peculiar neighbors and occurrences. When the wife becomes mysteriously pregnant, paranoia over the safety of her unborn child begins to control her life [content warning].

Slant: The middle child in Polanski’s nightmarish apartment trilogy (between Repulsion and The Tenant), Rosemary’s Baby is one of horror cinema’s all-time slow burns, drawing viewers gradually into entertaining the possibility that the movie’s series of strange coincidences and accumulating sense of dread are only subjective representations of Rosemary’s unraveling mental state. In other words, Polanski plants seeds of doubt as expertly as Rosemary believes the coven next door has arranged to snatch her baby from her to use in their rituals. And Polanski’s ability to prime the audience into questioning, if not outright rejecting, Rosemary’s suspicions gives it an unsettling quality far outpacing many of the films it inspired (specifically the brutal but morally shallow The Exorcist, which renders the presence of demonic entities in stark black-and-white terms).

Every moment we choose to not believe Rosemary, regardless of the fact that we’re being led by the nose by Polanski, we become complicit in the set of values that, externally, continue to pollute the discourse surrounding pregnancy. Which is one of the reasons the movie’s single most upsetting betrayal comes not from Guy, not from Rosemary’s neighbors, not even from the Catholic Church itself, but rather from Charles Grodin’s Dr. Hill, the WASP-friendly obstetrician who Rosemary was convinced to dump in favor of Dr. Saperstein. Having finally resolved to sneak her way out from under the prying eyes of the Bramford’s residents and give birth the way she originally planned, Rosemary seeks sanctuary in Hill’s office. He puts her up in the back room and lets her sleep while he calls Guy and Dr. Saperstein, who swoop in to collect Rosemary and take her home. In one crushing gesture, Polanski implies that no man ever fully trusts women to know what’s best for themselves, and that they will always be dismissive of women’s judgment. So long as there are men in power who are still fuzzy on the definition of rape, Rosemary’s Baby will endure as a cautionary tale.

AV Club: Rosemary’s Baby isn’t a horror movie in the typical things-that-go-boo! sense. Polanski (who also wrote the screenplay, closely following Levin’s novel) is more interested in creating a creeping sense of unease by making everything seem plausible. Nearly every supernatural incident in Rosemary’s Baby can be read as a dream the heroine is having, exacerbated by her very ordinary worries: about an insensitive husband who’s always ducking out for suspicious reasons; about intrusive neighbors who aren’t shy about sharing their opinions; and about doctors with all kinds of weird, unconfirmable advice on diet and health for expectant mothers. It matters too that all of this is happening in New York, a city already full of kooky characters and old buildings with their own twisted histories. And it matters that it’s taking place in the mid-’60s, where Farrow falls between a generation of expected-to-be-submissive housewives and a generation of expected-to-be-self-actualized feminists.

Behind the scenes, Farrow faced a similar dilemma, as shooting on Rosemary’s Baby went on so long that it broke up her marriage to Frank Sinatra, leaving her an emotional wreck on the set toward the end. Meanwhile, Polanski clashed with Cassavetes, who preferred improvisation and rawness to Polanski’s yen for precision. But Polanski channeled all of that bad energy, aided by the support of veteran genre-movie producer William Castle and young Paramount executive Robert Evans. Polanski also relied heavily on the creative mix of gothic and modern sets from production designer Richard Sylbert, and the nerve-jangling score from Krzysztof Komeda. And he brought his own outsider’s sensibility, which he used to subtly satirize the pretensions of New York society types.

Roger Ebert: When the conclusion comes, it works not because it is a surprise but because it is horrifyingly inevitable. Rosemary makes her dreadful discovery, and we are wrenched because we knew what was going to happen--and couldn't help her.

This is why the movie is so good. The characters and the story transcend the plot. In most horror films, and indeed in most suspense films of the Alfred Hitchcock tradition, the characters are at the mercy of the plot. In this one, they emerge as human beings actually doing these things.

A great deal of the credit for this achievement must go to Mia Farrow, as Rosemary, and Ruth Gordon, as Mrs. Castevet, the next-door neighbor. Here are two of the finest performances by actresses this year.

Trailer

Streaming on Vimeo

Art of the Title

Filming Locations

The Most Cursed Hit Movie Ever Made

The Devil Inside: Watching Rosemary’s Baby in the Age of #MeToo

An Evil You Can't Explain: The Cult Power of Rosemary's Baby

The Most Disturbing Moments In "Rosemary's Baby" Actually Aren't Supernatural

Slant: The middle child in Polanski’s nightmarish apartment trilogy (between Repulsion and The Tenant), Rosemary’s Baby is one of horror cinema’s all-time slow burns, drawing viewers gradually into entertaining the possibility that the movie’s series of strange coincidences and accumulating sense of dread are only subjective representations of Rosemary’s unraveling mental state. In other words, Polanski plants seeds of doubt as expertly as Rosemary believes the coven next door has arranged to snatch her baby from her to use in their rituals. And Polanski’s ability to prime the audience into questioning, if not outright rejecting, Rosemary’s suspicions gives it an unsettling quality far outpacing many of the films it inspired (specifically the brutal but morally shallow The Exorcist, which renders the presence of demonic entities in stark black-and-white terms).

Every moment we choose to not believe Rosemary, regardless of the fact that we’re being led by the nose by Polanski, we become complicit in the set of values that, externally, continue to pollute the discourse surrounding pregnancy. Which is one of the reasons the movie’s single most upsetting betrayal comes not from Guy, not from Rosemary’s neighbors, not even from the Catholic Church itself, but rather from Charles Grodin’s Dr. Hill, the WASP-friendly obstetrician who Rosemary was convinced to dump in favor of Dr. Saperstein. Having finally resolved to sneak her way out from under the prying eyes of the Bramford’s residents and give birth the way she originally planned, Rosemary seeks sanctuary in Hill’s office. He puts her up in the back room and lets her sleep while he calls Guy and Dr. Saperstein, who swoop in to collect Rosemary and take her home. In one crushing gesture, Polanski implies that no man ever fully trusts women to know what’s best for themselves, and that they will always be dismissive of women’s judgment. So long as there are men in power who are still fuzzy on the definition of rape, Rosemary’s Baby will endure as a cautionary tale.

AV Club: Rosemary’s Baby isn’t a horror movie in the typical things-that-go-boo! sense. Polanski (who also wrote the screenplay, closely following Levin’s novel) is more interested in creating a creeping sense of unease by making everything seem plausible. Nearly every supernatural incident in Rosemary’s Baby can be read as a dream the heroine is having, exacerbated by her very ordinary worries: about an insensitive husband who’s always ducking out for suspicious reasons; about intrusive neighbors who aren’t shy about sharing their opinions; and about doctors with all kinds of weird, unconfirmable advice on diet and health for expectant mothers. It matters too that all of this is happening in New York, a city already full of kooky characters and old buildings with their own twisted histories. And it matters that it’s taking place in the mid-’60s, where Farrow falls between a generation of expected-to-be-submissive housewives and a generation of expected-to-be-self-actualized feminists.

Behind the scenes, Farrow faced a similar dilemma, as shooting on Rosemary’s Baby went on so long that it broke up her marriage to Frank Sinatra, leaving her an emotional wreck on the set toward the end. Meanwhile, Polanski clashed with Cassavetes, who preferred improvisation and rawness to Polanski’s yen for precision. But Polanski channeled all of that bad energy, aided by the support of veteran genre-movie producer William Castle and young Paramount executive Robert Evans. Polanski also relied heavily on the creative mix of gothic and modern sets from production designer Richard Sylbert, and the nerve-jangling score from Krzysztof Komeda. And he brought his own outsider’s sensibility, which he used to subtly satirize the pretensions of New York society types.

Roger Ebert: When the conclusion comes, it works not because it is a surprise but because it is horrifyingly inevitable. Rosemary makes her dreadful discovery, and we are wrenched because we knew what was going to happen--and couldn't help her.

This is why the movie is so good. The characters and the story transcend the plot. In most horror films, and indeed in most suspense films of the Alfred Hitchcock tradition, the characters are at the mercy of the plot. In this one, they emerge as human beings actually doing these things.

A great deal of the credit for this achievement must go to Mia Farrow, as Rosemary, and Ruth Gordon, as Mrs. Castevet, the next-door neighbor. Here are two of the finest performances by actresses this year.

Trailer

Streaming on Vimeo

Art of the Title

Filming Locations

The Most Cursed Hit Movie Ever Made

The Devil Inside: Watching Rosemary’s Baby in the Age of #MeToo

An Evil You Can't Explain: The Cult Power of Rosemary's Baby

The Most Disturbing Moments In "Rosemary's Baby" Actually Aren't Supernatural

It’s unfortunate that this film seems to have become nearly forgotten and/or shunned, in a way, by the public. It’s such a good watch.

posted by Thorzdad at 9:05 PM on June 30, 2018

posted by Thorzdad at 9:05 PM on June 30, 2018

nearly forgotten and/or shunned, in a way, by the public.

...it's the world's most famous, classic and iconic horror movie except for maybe The Exorcist and universally agreed to be much better art-wise, it's a touchstone and a lodestar for everything involving women and horror or feminism and horror or occult horror or psychological horror. the film of films, and cannot be watched more than once in a lifetime by any person of sensibility. but ok, maybe men forgot about it for a while, I wouldn't know about that. the rest of us never did.

it's also the final judgment on Roman Polanski in that it proves, really proves, that there is nothing about rape culture and misogyny he didn't understand, and that everything he did in his life, he did knowingly. it's a comprehensive confession-before-the-fact on film. there was no ignorance in him.

Julie Klausner has the final word on it starting at 29:18 here. all the final words. as she says, it is "as good for women as Roman Polanski is bad for them." and "Guy Woodhouse is the world's worst villain in any movie of all time." with respect to Slant, he's worse than Charles Grodin, even though Grodin is as bad as they say.

posted by queenofbithynia at 11:28 PM on June 30, 2018 [13 favorites]

...it's the world's most famous, classic and iconic horror movie except for maybe The Exorcist and universally agreed to be much better art-wise, it's a touchstone and a lodestar for everything involving women and horror or feminism and horror or occult horror or psychological horror. the film of films, and cannot be watched more than once in a lifetime by any person of sensibility. but ok, maybe men forgot about it for a while, I wouldn't know about that. the rest of us never did.

it's also the final judgment on Roman Polanski in that it proves, really proves, that there is nothing about rape culture and misogyny he didn't understand, and that everything he did in his life, he did knowingly. it's a comprehensive confession-before-the-fact on film. there was no ignorance in him.

Julie Klausner has the final word on it starting at 29:18 here. all the final words. as she says, it is "as good for women as Roman Polanski is bad for them." and "Guy Woodhouse is the world's worst villain in any movie of all time." with respect to Slant, he's worse than Charles Grodin, even though Grodin is as bad as they say.

posted by queenofbithynia at 11:28 PM on June 30, 2018 [13 favorites]

I have seen more than once, but I am probably not a person of sensibility. It's perfect in so many ways. John Cassavetes' Guy is .. just an incredible portrayal of a horrible person. I love the moment after the party, when Rosemary is fighting back, and Guy's excuses get lamer and lamer, and he finally says, "It wouldn't be fair to Dr. Saperstein" with a little laugh, he can't help but laugh at how absurd the arguments he's making are. (It reminds me of a stage play, not a movie, and Rosemary's Baby is a lot like a stage play but with zero affected staginess.)

For what is almost a kind of horror standard ("a couple moves into a cabin, the villagers are cultists") it works because for almost all of the movie, the encounters manifest as completely mundane things and until the end there is never any kind of supernatural spookiness at all. It's barely metaphorical.

posted by fleacircus at 2:30 AM on July 1, 2018 [4 favorites]

For what is almost a kind of horror standard ("a couple moves into a cabin, the villagers are cultists") it works because for almost all of the movie, the encounters manifest as completely mundane things and until the end there is never any kind of supernatural spookiness at all. It's barely metaphorical.

posted by fleacircus at 2:30 AM on July 1, 2018 [4 favorites]

I can't watch it again mainly because of my weakness & delicacy but also I don't need to, I remember every scene perfectly from a single viewing 20 years ago. most things I forget half of even while they're happening, but it's that good.

if only I were a teen with an overdue term paper I'd say some bullshit about how Bob Hoskins is the John Cassavetes of Alien, & Ripley's canny evasion of devil-pregnancy is both what allows her to have the escape denied to Mia Farrow and the thing that makes those films ultimately consolatory fantasy (albeit the best of fantasies) and Rosemary's Baby brutal social realism

there's no catharsis in RB & no hope, you get past a certain point and even if Rosemary got away from her husband, from the cult, out of New York, found 1968's only respectful ob-gyn, everyone believed her and cared for her, it would all be for nothing because she'd still be pregnant. no way out of the horror, you just have to wait until the horror makes its own way out of you.

posted by queenofbithynia at 10:18 AM on July 1, 2018 [5 favorites]

if only I were a teen with an overdue term paper I'd say some bullshit about how Bob Hoskins is the John Cassavetes of Alien, & Ripley's canny evasion of devil-pregnancy is both what allows her to have the escape denied to Mia Farrow and the thing that makes those films ultimately consolatory fantasy (albeit the best of fantasies) and Rosemary's Baby brutal social realism

there's no catharsis in RB & no hope, you get past a certain point and even if Rosemary got away from her husband, from the cult, out of New York, found 1968's only respectful ob-gyn, everyone believed her and cared for her, it would all be for nothing because she'd still be pregnant. no way out of the horror, you just have to wait until the horror makes its own way out of you.

posted by queenofbithynia at 10:18 AM on July 1, 2018 [5 favorites]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Pope Guilty at 4:13 PM on June 30, 2018 [2 favorites]