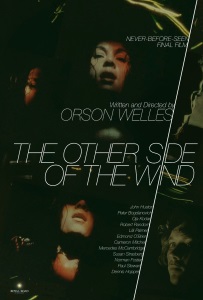

The Other Side of the Wind (2018)

November 3, 2018 6:43 PM - Subscribe

Surrounded by fans and skeptics, grizzled director J.J. "Jake" Hannaford returns from years abroad in Europe to a changed Hollywood, where he attempts to make his innovative comeback film.

Forty-eight years in the making, Orson Welles' final film is finally finished and released by Netflix to mostly positive reviews.

Glenn Kenny at Rogerebert.com:

Forty-eight years in the making, Orson Welles' final film is finally finished and released by Netflix to mostly positive reviews.

Glenn Kenny at Rogerebert.com:

In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1968 film “La Chinoise,” one of the characters, Kirilov, announces, “L’art ne pas le reflet du réel, mais le reel de ce reflet.” Which translates as “Art is not the reflection of reality, it’s the reality of the reflection.” In “The Other Side of the Wind,” a film shot in the years between 1970 and 1976 and later (only partially) edited by Orson Welles, a character named Mr. Pister, a very young, whippet thin and presumably callow square of a film critic—played, not coincidentally, by Joseph McBride, who would go on to become, besides a fine critic and scholar in general, one of the key voices keeping Welles’ often misunderstood legacy alive—asks its bete noire-legendary director figure, Jake Hannaford, “Is the camera eye a reflection of reality or is reality a reflection of the camera eye?”Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at AVClub:

The familiar Welles themes (illusion, identity, memory, betrayal) are present and accounted for. But there are darker forces at work—links between Hollywood’s dirty past (HUAC in particular) and its paranoid present, self-expression and self-repression. To some extent, these are embodied by Hannaford, a self-parodying amalgam of Welles, Huston, and various macho writers and directors of the older generation. One of the more obvious contradictions of the film is that, despite its mockumentary collage (a mix of 16mm and 35mm, color and black-and-white), no one in Wind gives anything like a naturalistic performance. (Huston, for one, chews his lines like cud.) They are pure movie people, mugging for a camera that keeps framing them through smoke and slats. Their reality is one of constant competition, rejection, and internalized pretending—and though the cutting (started by Welles and completed in a Herculean effort by Bob Murawski) is split-second, it looks a lot like theater. At one point, the lights go out and everyone starts bumbling around with hurricane lanterns, which only adds to the impression of the party as a feudal hall.Michael Phillips at The Chicago Tribune:

Each film by Orson Welles feels like a first film, wrestled into shape by an artist working by instinct as well as craft. The two-hour version now available of Welles’ last first film, “The Other Side of the Wind,” exists as … well, it exists, which is miracle enough.

----

Welles wanted to pull the rug out from under the town, and the industry, that enticed and then betrayed him. “The Other Side of the Wind” plays like Luigi Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author,” only it’s more like “Six Movies in Search of Their Maker.” It’s a film that refused to be completed about a film that refuses to be completed, featuring a cast of real-life emblems of Old Hollywood (George Jessel is in it, for one) in proximity to exemplars of New Hollywood (Dennis Hopper, hot off “Easy Rider” but cold off “The Last Movie,” pops in to talk about how he’d like “John Wayne’s audience to see my movie”).

I haven't watched this yet, but I did watch the companion documentary "They'll Love Me When I'm Dead" on Netflix over the weekend and would recommend it highly if you want to know more about the prolonged and problematic making of this film.

posted by briank at 6:51 AM on November 6, 2018 [1 favorite]

posted by briank at 6:51 AM on November 6, 2018 [1 favorite]

I second that recommendation. The documentary does a good job of getting into the head of Welles who really was the definition of the self-destructing genius.

posted by octothorpe at 10:08 AM on November 6, 2018

posted by octothorpe at 10:08 AM on November 6, 2018

I’m not going to talk about this movie right now. Instead I’m going to talk about another, worse movie, The Cat’s Meow, which was released in 2001 and directed by one Peter Bogdanovich. This is (sort of) based on the true story of the mysterious death of film mogul Thomas H. Ince that occurred on William Randolph Hearst's boat with Charles Chaplin on board.

Now Charles Chaplin, of course, is a film director who made a habit of hooking up with the teenage stars of his movies, and Bogdanovich also happens to be a director who made a habit of hooking up with the teenage stars of his movies. So there’s a whole bunch of metatext behind this movie, which is something that Bogdanovich obviously picked up from his mentor, Orson Welles.

But! In the film, Chaplin is portrayed very sympathetically. He’s a decent guy, really! When Welles portrays himself on screen, he really doesn’t care what other people think about him; he is more than willing to put all of his self-loathing on display. Bogdanovich, however, is incapable of that. Also, in the film, Hearst is the movie’s antihero, and Chaplin is supposed to be the antagonist; the pot-stirrer who drives the plot. By portraying him so apologetically, all of the drama gets sucked out of the film. Instead of the metatext enhancing the story, it drags the story down.

That, my friends, is the difference between a great director and a not-so-great one.

posted by 1970s Antihero at 12:15 PM on November 6, 2018

Now Charles Chaplin, of course, is a film director who made a habit of hooking up with the teenage stars of his movies, and Bogdanovich also happens to be a director who made a habit of hooking up with the teenage stars of his movies. So there’s a whole bunch of metatext behind this movie, which is something that Bogdanovich obviously picked up from his mentor, Orson Welles.

But! In the film, Chaplin is portrayed very sympathetically. He’s a decent guy, really! When Welles portrays himself on screen, he really doesn’t care what other people think about him; he is more than willing to put all of his self-loathing on display. Bogdanovich, however, is incapable of that. Also, in the film, Hearst is the movie’s antihero, and Chaplin is supposed to be the antagonist; the pot-stirrer who drives the plot. By portraying him so apologetically, all of the drama gets sucked out of the film. Instead of the metatext enhancing the story, it drags the story down.

That, my friends, is the difference between a great director and a not-so-great one.

posted by 1970s Antihero at 12:15 PM on November 6, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

For a film that was shot over about five years with multiple cast changes along the way and edited off and on for forty years, it's actually a pretty cohesive work and not really hard to follow. The editing and constant changes of film stock seem to predict the stuff that Oliver Stone and Tony Scott were doing in the '90s and the film-within-the-film is just so hilarious. It's like one long 1970s perfume commercial but x-rated.

The main performance by Huston is wonderful and it's too bad that he didn't live to see the film completed either. The fun thing is to wonder what the world would have thought of this movie if it had been completed in 1974 or so. It would have probably only been seen in some film festivals and art cinemas and would have been seen as a odd footnote to Welles' career.

posted by octothorpe at 1:41 PM on November 4, 2018 [2 favorites]