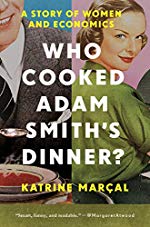

Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner?

April 25, 2019 12:47 PM - by Katrine Marcal - Subscribe

A funny, clever, and thought-provoking examination of the myth of the "economic man" and its impact on the global economy

How do you get your dinner? That is the basic question of economics. When economist and philosopher Adam Smith proclaimed that all our actions were motivated by self-interest, he used the example of the baker and the butcher as he laid the foundations for 'economic man.' He argued that the baker and butcher didn't give bread and meat out of the goodness of their hearts. It's an ironic point of view coming from a bachelor who lived with his mother for most of his life ― a woman who cooked his dinner every night.

Nevertheless, the economic man has dominated our understanding of modern-day capitalism, with a focus on self-interest and the exclusion of all other motivations. Such a view point disregards the unpaid work of mothering, caring, cleaning and cooking. It insists that if women are paid less, then that's because their labor is worth less. Economics has told us a story about how the world works and we have swallowed it, hook, line and sinker. This story has not served women well. Now it's time to change it.

A kind of femininst Freakonomics, Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? charts the myth of economic man ― from its origins at Adam Smith's dinner table, its adaptation by the Chicago School, and its disastrous role in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis ― in a witty and courageous dismantling of one of the biggest myths of our time.

Nevertheless, the economic man has dominated our understanding of modern-day capitalism, with a focus on self-interest and the exclusion of all other motivations. Such a view point disregards the unpaid work of mothering, caring, cleaning and cooking. It insists that if women are paid less, then that's because their labor is worth less. Economics has told us a story about how the world works and we have swallowed it, hook, line and sinker. This story has not served women well. Now it's time to change it.

A kind of femininst Freakonomics, Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? charts the myth of economic man ― from its origins at Adam Smith's dinner table, its adaptation by the Chicago School, and its disastrous role in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis ― in a witty and courageous dismantling of one of the biggest myths of our time.

I haven't read the book, but does it give any evidence for supposing that Adam Smith's dinner was cooked by his mother rather than by a domestic servant? Smith was a wealthy man, with an annual salary of £600, and could easily have afforded to pay for a cook. This isn't just a pedantic point, as the distinction between paid and unpaid labour appears to be rather crucial to the book's argument.

posted by verstegan at 9:37 AM on April 27, 2019 [1 favorite]

posted by verstegan at 9:37 AM on April 27, 2019 [1 favorite]

It’s fairly clearly laid out in the book which I recommend you read.

posted by Homo neanderthalensis at 11:15 AM on April 27, 2019 [1 favorite]

posted by Homo neanderthalensis at 11:15 AM on April 27, 2019 [1 favorite]

Ok, out of curiosity, I've been looking to see if I can find the answer to verstegan's question. As far as I can see from online previews, in the book, the actual biography of Smith and his mother are only addressed for a page or so; it's not the author's point. The question "did Smith's mother literally cook or did she arrange for dinner to be made by a servant?" isn't addressed, or I didn't find it anyway. But that's fine, it's only the broader point that the author is after -- the gaps in Smith-ian economic thinking this general kind of example points to.

Quick facts as far as I gleaned from this and the Rea biography she cites: Smith's mother Margaret Douglas was from a noble family, married a much older man, was shortly widowed and never remarried. Smith was an only child. He and his mother, and a cousin Janet, lived together for most of the next 60 years. Smith was a homebody and very close with both of them. The mother "tended the household" and the cousin "handled [Smith's] finances." Given their social class it seems likely the actual cooking was mostly done by a servant -- but that just means Smith's mother contributed a different type of unpaid labor, "running the household" in the sense of hiring and supervising servants, making pantry decisions etc. The book says she "made sure dinner was on the table," and that's as much detail as it cares about, so ok.

Nothing in the book hinges on this as far as I can tell from a skim; it's being used only as a rhetorical jumping-off point, not as evidence for anything. There's no reason to debate that many mothers do cook dinner, unpaid, out of motives other than sheer self-interest. And the author also says, for the butcher et al in the famous quote to do their trades, they're relying on women at home cooking and cleaning and so on. So the point stands, that the recognized male economic activity is sitting on top of women's unrecognized labor.

posted by LobsterMitten at 1:47 PM on April 27, 2019 [3 favorites]

Quick facts as far as I gleaned from this and the Rea biography she cites: Smith's mother Margaret Douglas was from a noble family, married a much older man, was shortly widowed and never remarried. Smith was an only child. He and his mother, and a cousin Janet, lived together for most of the next 60 years. Smith was a homebody and very close with both of them. The mother "tended the household" and the cousin "handled [Smith's] finances." Given their social class it seems likely the actual cooking was mostly done by a servant -- but that just means Smith's mother contributed a different type of unpaid labor, "running the household" in the sense of hiring and supervising servants, making pantry decisions etc. The book says she "made sure dinner was on the table," and that's as much detail as it cares about, so ok.

Nothing in the book hinges on this as far as I can tell from a skim; it's being used only as a rhetorical jumping-off point, not as evidence for anything. There's no reason to debate that many mothers do cook dinner, unpaid, out of motives other than sheer self-interest. And the author also says, for the butcher et al in the famous quote to do their trades, they're relying on women at home cooking and cleaning and so on. So the point stands, that the recognized male economic activity is sitting on top of women's unrecognized labor.

posted by LobsterMitten at 1:47 PM on April 27, 2019 [3 favorites]

Thanks for the helpful response! It sounds as though, despite the title, the book is more about economics than economic history. Which is fine: I get that the author is using Adam Smith to make a point about women's invisible labour, though it does seem a bit ironic that, in doing so, she doesn't see fit to mention the role of domestic servants.

It's worth noting, by the way, that economic historians have recently been re-examining Smith's famous example of the pin factory, which he uses to illustrate the division of labour. Amy Erickson has shown that in reality, pin-making was dominated by female labour. This could have provided powerful support for Katrine Marcal's argument, but from the preview on Google Books, it looks as though she doesn't have much to say about women's work outside the home. Which, again, is fine: I get that she's not writing a work of history. It just feels like a missed opportunity to give her argument an extra historical dimension.

posted by verstegan at 6:27 AM on April 28, 2019 [2 favorites]

It's worth noting, by the way, that economic historians have recently been re-examining Smith's famous example of the pin factory, which he uses to illustrate the division of labour. Amy Erickson has shown that in reality, pin-making was dominated by female labour. This could have provided powerful support for Katrine Marcal's argument, but from the preview on Google Books, it looks as though she doesn't have much to say about women's work outside the home. Which, again, is fine: I get that she's not writing a work of history. It just feels like a missed opportunity to give her argument an extra historical dimension.

posted by verstegan at 6:27 AM on April 28, 2019 [2 favorites]

I get that the author is using Adam Smith to make a point about women's invisible labour, though it does seem a bit ironic that, in doing so, she doesn't see fit to mention the role of domestic servants.

I don't think the point is women's invisible labor, it is unpaid labor (often also invisible) which is widely ignored in economic theory.

So while domestic service is an occupation that deserves more credit and attention, this book is about labor which is unpaid, and what it means for the usefulness and accuracy of economic theories which rest on ignoring work done by half the population.

It's been a while since I read it; I will see if I can find it again and get a refresher on some of the details.

posted by Emmy Rae at 5:18 AM on April 29, 2019 [1 favorite]

I don't think the point is women's invisible labor, it is unpaid labor (often also invisible) which is widely ignored in economic theory.

So while domestic service is an occupation that deserves more credit and attention, this book is about labor which is unpaid, and what it means for the usefulness and accuracy of economic theories which rest on ignoring work done by half the population.

It's been a while since I read it; I will see if I can find it again and get a refresher on some of the details.

posted by Emmy Rae at 5:18 AM on April 29, 2019 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Homo neanderthalensis at 12:52 PM on April 25, 2019 [6 favorites]