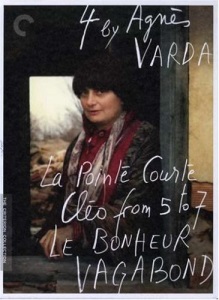

Le Bonheur (1965)

January 6, 2024 3:07 PM - Subscribe

Francois, a young carpenter, lives a happy, uncomplicated life with his wife Therese and their two small children. One day he meets Emilie, a clerk in the local post office.

In suburban Paris, young François (Jean-Claude Drouot) appears to live a happy, contented existence with his wife, Therese (Claire Drouot), and their two small children. Despite his apparent satisfaction, François takes a mistress named Emilie (Marie-France Boyer), and, remarkably, doesn't feel the least bit of remorse for his philandering. While he is able to justify loving both women, François' infidelity results in tragic real-life consequences for both him and his family.

Ian Thomas Malone: Varda throws shade at the idea of a perfect life. Love is not a programmable equation. The heart wants what it wants, even when that doesn’t make any sense to anyone around us. Le Bonheur dazzles with its gorgeous cinematography, but its narrative packs a quiet punch that doesn’t quite hit you until you start to try and unpack all the themes that Varda stuffed into her brisk 80-minute runtime. Sometimes people do bad things for reasons that are neither good nor bad. Life is messy.

Amy Taubin: More than Le bonheur’s feminist politics and the fact that they were slightly ahead of their time, it is on the level of form that the film is so unsettling and calls up so many contradictory interpretations. One need only look at the opening and closing scenes to understand the complexity of Varda’s strategy. Le bonheur begins with a montage of flowers and foliage growing wild in the countryside. The sequence is anchored by repeated close-ups of sunflowers, their jaunty yellow petals just a bit ragged and faded around the edges. The editing rhythms are extremely aggressive. It’s not pastoral beauty that Varda is forcing us to see but a wildness and asymmetry that defies conventional representation and, certainly, the clichéd metaphors François is so fond of employing. The montage is scored to a late Mozart woodwind quintet, its relentless vivacity undercut by its minor mode. Neither the image nor the music is quite as celebratory as it might immediately seem. Hardly the signifiers of pure happiness, they both take on an increasingly mordant tone, which doesn’t entirely dissipate when the camera turns its attention to the family picnicking in the grass.

Abby Monteil: Upon its release, Le bonheur was criticised for what some saw as a literal endorsement of the submissive women and entrenched gender roles presented on screen. And while it’s true that Thérèse and Émilie are far less emboldened than the rich female protagonists of other Varda films, like Cléo from 5 to 7, One Sings, The Other Doesn’t, and Vagabond, the director’s feminist satire isn’t any less subversive. By placing an emphasis on nature and happiness and crafting a deceptively gorgeous exterior, she lulls viewers into entertaining Francois’ sunny view of “free love.” But through callously swapping the main women at the movie’s end, Varda makes it clear that her male protagonist isn’t genuinely interested in healthy polyamory — instead, living in a patriarchal society that strictly prioritises monogamous family life, he relies on women to keep his everyday affairs in order and provide him with unlimited romantic and sexual fulfilment.

Trailer

In suburban Paris, young François (Jean-Claude Drouot) appears to live a happy, contented existence with his wife, Therese (Claire Drouot), and their two small children. Despite his apparent satisfaction, François takes a mistress named Emilie (Marie-France Boyer), and, remarkably, doesn't feel the least bit of remorse for his philandering. While he is able to justify loving both women, François' infidelity results in tragic real-life consequences for both him and his family.

Ian Thomas Malone: Varda throws shade at the idea of a perfect life. Love is not a programmable equation. The heart wants what it wants, even when that doesn’t make any sense to anyone around us. Le Bonheur dazzles with its gorgeous cinematography, but its narrative packs a quiet punch that doesn’t quite hit you until you start to try and unpack all the themes that Varda stuffed into her brisk 80-minute runtime. Sometimes people do bad things for reasons that are neither good nor bad. Life is messy.

Amy Taubin: More than Le bonheur’s feminist politics and the fact that they were slightly ahead of their time, it is on the level of form that the film is so unsettling and calls up so many contradictory interpretations. One need only look at the opening and closing scenes to understand the complexity of Varda’s strategy. Le bonheur begins with a montage of flowers and foliage growing wild in the countryside. The sequence is anchored by repeated close-ups of sunflowers, their jaunty yellow petals just a bit ragged and faded around the edges. The editing rhythms are extremely aggressive. It’s not pastoral beauty that Varda is forcing us to see but a wildness and asymmetry that defies conventional representation and, certainly, the clichéd metaphors François is so fond of employing. The montage is scored to a late Mozart woodwind quintet, its relentless vivacity undercut by its minor mode. Neither the image nor the music is quite as celebratory as it might immediately seem. Hardly the signifiers of pure happiness, they both take on an increasingly mordant tone, which doesn’t entirely dissipate when the camera turns its attention to the family picnicking in the grass.

Abby Monteil: Upon its release, Le bonheur was criticised for what some saw as a literal endorsement of the submissive women and entrenched gender roles presented on screen. And while it’s true that Thérèse and Émilie are far less emboldened than the rich female protagonists of other Varda films, like Cléo from 5 to 7, One Sings, The Other Doesn’t, and Vagabond, the director’s feminist satire isn’t any less subversive. By placing an emphasis on nature and happiness and crafting a deceptively gorgeous exterior, she lulls viewers into entertaining Francois’ sunny view of “free love.” But through callously swapping the main women at the movie’s end, Varda makes it clear that her male protagonist isn’t genuinely interested in healthy polyamory — instead, living in a patriarchal society that strictly prioritises monogamous family life, he relies on women to keep his everyday affairs in order and provide him with unlimited romantic and sexual fulfilment.

Trailer

I adore Agnès Varda and I love how subtly complicated this movie is. It's on everyone's side, somewhat, because life is messy.

I also absolutely agree with everyone that this is actually a horror movie. It creeps up on you and the last moments really change the whole aesthetic of it.

Like I said, I love Varda. Her films were heartfelt and complicated. I need to watch this again but it's also a very uncomfortable watch. It's meant to be.

posted by edencosmic at 6:51 PM on January 6, 2024 [1 favorite]

I also absolutely agree with everyone that this is actually a horror movie. It creeps up on you and the last moments really change the whole aesthetic of it.

Like I said, I love Varda. Her films were heartfelt and complicated. I need to watch this again but it's also a very uncomfortable watch. It's meant to be.

posted by edencosmic at 6:51 PM on January 6, 2024 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Carillon at 3:09 PM on January 6, 2024 [3 favorites]