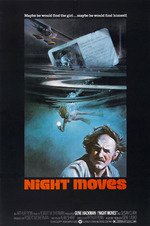

Night Moves (1975)

April 20, 2016 6:10 PM - Subscribe

Los Angeles private detective Harry Moseby is hired by a client to find her runaway teenage daughter and he stumbles upon a case of murder and artifact smuggling.

Crime Culture: In his 1940s heyday the private detective was a transgressor who could move across boundaries of good and evil to the dark side with ease (hence his appeal) in a society of innocents. By the 70s so much had changed that society itself was transgressive, and the dick could be the only ingenue , the last innocent. Such is the case in Night Moves.

NYTimes: Over the years we have come to expect our private eyes to be somewhat seedy and second-rate, beer-drinking loners with their own secrets to hide. But that seediness, as well as the decency that lurked beneath, has always been in the service of the genres. One never worried about Philip Marlowe's mental health; one does about Harry Moseby's. In fact, Harry is much more interesting and truly complex than the mystery he sets out to solve.

Roger Ebert: The plot can be understood, but not easily, and not on first viewing, and besides, the point is that Moseby is as lost as we are. Something is always turning up to force him to revise everything he thought he knew, and then at the end of the film he has to revise everything again, and there is a shot where one of the characters, while drowning, seems to be desperately shaking his head as if to say -- what? "I didn't mean to do this"? "I didn't know who was in the boat"? "In the water"? "You don't understand"?

Harry doesn't understand, that's for sure, and the last shot in the film, taken from high above, shows him in a boat that is circling aimlessly in the Gulf Stream, a splendid metaphor for Harry's investigation.

AV Club: Night Moves tends to get filed away as an Arthur Penn movie, and it arguably concludes the string of classics he kicked off eight years earlier with Bonnie and Clyde. But it’s also recognizably the vision of screenwriter Alan Sharp, who passed away just a couple of months ago and was also responsible for such uncompromising pictures as Ulzana’s Raid (directed by Robert Aldrich) and The Hired Hand (directed by Peter Fonda). Here, Sharp simultaneously honors and subverts the conventions of the private-eye flick, teasing out tantalizing story strands but restricting the audience’s perspective to that of the film’s generally clueless protagonist. He also gives Hackman one of the greatest roles of the actor’s storied career: a belligerent, proud, dangerously resourceful hunk of misdirected tenacity. At one point, the man likens watching an Eric Rohmer movie to watching paint dry, by way of asserting his masculinity. It’s a funny line, but also ironic; Rohmer’s contradictory, messed-up, deeply human characters would surely recognize a kindred spirit.

Senses of Cinema: Penn has several times said that the mood of the film was a consequence of the Kennedy assassinations in 1963 and 1968 (he worked for both John and Robert) and the killing of the Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics (which he witnessed). “This was a period,” he said in 1994, “when we’d had all those assassinations in America. It was a terrible period, and I felt we were wandering around in a kind of blindness unaware of what we were doing to ourselves. It was a crazy period, and I thought we should tell this detective story in a way that could only be understood by what we see, not by what we are told. That’s the way the film ends. We learn who has been doing these things at the exact same moment Harry Moseby learns it: by looking through the glass–bottomed boat.”

Film Noir of the Week: Parsing Gene Hackman's singular gifts is a sucker's game. He just is. Hackman doesn't look, speak, dress or move like a movie star. He has little grace and sports the gnarliest mid-'70s hair/mustache combo in the history of gnarly mid-'70s hair/mustache combos. Yet he commands every moment. His character - Harry Moseby - a pro football player turned second-rate private eye, lives out his self-loathing the same way he lived out its only escape - through his body. The more Harry Moseby's lied to, or the more his feelings are hurt - and they're hurt easily -- the more slumped, crushed and childlike his posture becomes. When Moseby channels all his self-directed psychic violence outward - as he did on the football field - he's ecstatic. It's not Penn who communicates the depths of Harry's indifference to the outcome; it's Hackman. Harry doesn't care if he wins or loses, if he beats or is beaten. He wants only the release of the moment, regardless of consequences. He wants only to escape himself.

'Night Moves,' Explained

Trailer

Crime Culture: In his 1940s heyday the private detective was a transgressor who could move across boundaries of good and evil to the dark side with ease (hence his appeal) in a society of innocents. By the 70s so much had changed that society itself was transgressive, and the dick could be the only ingenue , the last innocent. Such is the case in Night Moves.

NYTimes: Over the years we have come to expect our private eyes to be somewhat seedy and second-rate, beer-drinking loners with their own secrets to hide. But that seediness, as well as the decency that lurked beneath, has always been in the service of the genres. One never worried about Philip Marlowe's mental health; one does about Harry Moseby's. In fact, Harry is much more interesting and truly complex than the mystery he sets out to solve.

Roger Ebert: The plot can be understood, but not easily, and not on first viewing, and besides, the point is that Moseby is as lost as we are. Something is always turning up to force him to revise everything he thought he knew, and then at the end of the film he has to revise everything again, and there is a shot where one of the characters, while drowning, seems to be desperately shaking his head as if to say -- what? "I didn't mean to do this"? "I didn't know who was in the boat"? "In the water"? "You don't understand"?

Harry doesn't understand, that's for sure, and the last shot in the film, taken from high above, shows him in a boat that is circling aimlessly in the Gulf Stream, a splendid metaphor for Harry's investigation.

AV Club: Night Moves tends to get filed away as an Arthur Penn movie, and it arguably concludes the string of classics he kicked off eight years earlier with Bonnie and Clyde. But it’s also recognizably the vision of screenwriter Alan Sharp, who passed away just a couple of months ago and was also responsible for such uncompromising pictures as Ulzana’s Raid (directed by Robert Aldrich) and The Hired Hand (directed by Peter Fonda). Here, Sharp simultaneously honors and subverts the conventions of the private-eye flick, teasing out tantalizing story strands but restricting the audience’s perspective to that of the film’s generally clueless protagonist. He also gives Hackman one of the greatest roles of the actor’s storied career: a belligerent, proud, dangerously resourceful hunk of misdirected tenacity. At one point, the man likens watching an Eric Rohmer movie to watching paint dry, by way of asserting his masculinity. It’s a funny line, but also ironic; Rohmer’s contradictory, messed-up, deeply human characters would surely recognize a kindred spirit.

Senses of Cinema: Penn has several times said that the mood of the film was a consequence of the Kennedy assassinations in 1963 and 1968 (he worked for both John and Robert) and the killing of the Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics (which he witnessed). “This was a period,” he said in 1994, “when we’d had all those assassinations in America. It was a terrible period, and I felt we were wandering around in a kind of blindness unaware of what we were doing to ourselves. It was a crazy period, and I thought we should tell this detective story in a way that could only be understood by what we see, not by what we are told. That’s the way the film ends. We learn who has been doing these things at the exact same moment Harry Moseby learns it: by looking through the glass–bottomed boat.”

Film Noir of the Week: Parsing Gene Hackman's singular gifts is a sucker's game. He just is. Hackman doesn't look, speak, dress or move like a movie star. He has little grace and sports the gnarliest mid-'70s hair/mustache combo in the history of gnarly mid-'70s hair/mustache combos. Yet he commands every moment. His character - Harry Moseby - a pro football player turned second-rate private eye, lives out his self-loathing the same way he lived out its only escape - through his body. The more Harry Moseby's lied to, or the more his feelings are hurt - and they're hurt easily -- the more slumped, crushed and childlike his posture becomes. When Moseby channels all his self-directed psychic violence outward - as he did on the football field - he's ecstatic. It's not Penn who communicates the depths of Harry's indifference to the outcome; it's Hackman. Harry doesn't care if he wins or loses, if he beats or is beaten. He wants only the release of the moment, regardless of consequences. He wants only to escape himself.

'Night Moves,' Explained

Trailer

This is a great film, and that soundtrack, for its limited roll, is lodged in my brain. That's in part because I keep playing it, thanks to this YouTube clip of Michael Small's score in the film. As noted in this Film Score Monthly message board thread, the master tapes were lost, making an official score unlikely, which is a bloody shame.

If you come across this Soundtrack Collector forum thread, the final comment states that the theme is on the CD "Screenthemes II," they are wrong and again mistook Inside Moves (trailer) for Night Moves, much to my sadness.

Also to my sadness, Discogs lists a few releases in Michael Small's fan-made discography that include "Night Moves," and while both Dee Dee Bridgewater and Shirley Bassey do have songs by that name with writing credits to Small, they're upbeat, positive vocal tracks that use the same backbone of the theme, mocking me all the more.

Maybe someday when I befriend a jazz group, or am ridiculously wealthy, I'll get someone to re-make that score. I'll stop here, because clearly I'm obsessed with this tune.

posted by filthy light thief at 8:12 PM on April 14, 2018 [1 favorite]

If you come across this Soundtrack Collector forum thread, the final comment states that the theme is on the CD "Screenthemes II," they are wrong and again mistook Inside Moves (trailer) for Night Moves, much to my sadness.

Also to my sadness, Discogs lists a few releases in Michael Small's fan-made discography that include "Night Moves," and while both Dee Dee Bridgewater and Shirley Bassey do have songs by that name with writing credits to Small, they're upbeat, positive vocal tracks that use the same backbone of the theme, mocking me all the more.

Maybe someday when I befriend a jazz group, or am ridiculously wealthy, I'll get someone to re-make that score. I'll stop here, because clearly I'm obsessed with this tune.

posted by filthy light thief at 8:12 PM on April 14, 2018 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Orangette_Coleman at 1:02 PM on April 21, 2016