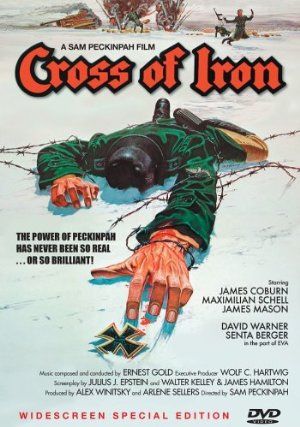

Cross of Iron (1977)

April 30, 2016 11:01 AM - Subscribe

A squad of German soldiers fighting on the Eastern Front during WWII led by a battle-hardened sergeant fight to survive Soviet attacks and dogmatic commanders in a chaotic and lethal environment in this sympathetic portrayal of another side of the war not commonly portrayed in Hollywood film.

Senses of Cinema: When Orson Welles first saw Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron (1977) he cabled Peckinpah that it was the best anti-war film he had ever seen about the “ordinary enlisted man”. Although Peckinpah’s earlier film Major Dundee (1965) deals with some of the ramifications of the US Civil War, Cross of Iron establishes its story firmly in the front line of war, depicting its horrors and the psychological damage it inflicts on its participants. Made in Yugoslavia on a low budget, this sombre and claustrophobic film deals with a German reconnaissance platoon involved in the retreat from the Russian front. A commercial failure in America, it was released in Europe in the spring of 1977 to rave reviews. In Germany it was awarded a Bambi and, ironically, it became the biggest grossing film in Germany and Austria since The Sound of Music (Robert Wise, 1965).

Amongst the mud, slaughter and wreckage, against the endless, harsh, bone-shattering explosions and flashing lights, Steiner attempts to protect the men under his command. Like many of Peckinpah’s protagonists, Steiner is an independent and anarchic character who detests all forms of authority. Although a highly decorated Sergeant, who somehow always manages to cheat death, he detests the uniform he wears and everything it stands for. His nemesis appears in the figure of the oily-haired and pink-cheeked Captain Stransky (Maximillian Schell). A wealthy aristocratic Prussian, Stransky has volunteered for the front with the express aim of winning the “Iron Cross” (awarded to German soldiers for extreme bravery). An increasing animosity develops between the two men with Stransky eventually taking murderous actions. Under his command, Steiner’s platoon is abandoned behind enemy lines, where almost all of them eventually perish.

In some ways, the film’s narrative is of peripheral importance. What it does is mark out situations where psychological dramas and emotive actions can be explored. Even in the context of Peckinpah’s oeuvre this is a film of extreme actions and moments. We see the horrific scars and amputations of wounded soldiers, vehicles drive over dead bodies, silent orgiastic killings take place, anonymous figures are blown to smithereens, and soldiers are shot by their own sides. In this film Peckinpah returns to the explosive sequences of violence that we find in The Wild Bunch (1969); however, he is less concerned with the ecstatic function of violence and more meditative about the characters who participate in its action and whose fates often seem inevitable. A strange complexity and lyricism infuses sequences in which he delves into the function of war and the reasons why men join armies and fight, while surreal, dream-like sequences explore the psychological damage inflicted on these men.

However, in Cross of Iron, as with most of Peckinpah’s films, there is a dual pulse beating. Amongst the destruction, betrayal and violence we also find a humanising love, sensuality and sweetness. Stransky bullies and manipulates a young orderly into confessing that his Captain is homosexual. Stransky then uses this information to blackmail the Captain under threat of banishment and hanging. In Steiner’s bunker, amidst the stench and dirt, his men comfort each other-touch, fondle and hug. Wearing an apron, the group’s scavenger and cook greets a new recruit by blowing him a kiss. The unshaven and scruffy Kruger (Klaus Lowitsch) literally kisses away the rising hysteria in a fellow soldier. The platoon cares for the enemy soldier boy, they have a birthday party, bake a cake, drink, sing and laugh. However, for all the sweetness and dignity that Peckinpah affords Steiner and his soldiers, he appears incapable of viewing female soldiers in the same light. Steiner and his men come across a group of female Russian Soldiers. These women are portrayed as incapable of fair combat, they resort to using their sexuality to trick and cajole Steiner’s men. The misogyny of this sequence is palpable as the female soldiers are ultimately portrayed as a pack of dogs circling helpless prey. Yet women, children, and the notion of home haunt this world of men. While injured in hospital Steiner has an affair with his nurse Eva (Senta Berger). She offers him the possibility of something better-sensuality, beauty and a home. Kruger refuses to wash in the belief that dirt and natural body oils will keep him waterproof. While trying to find their way back through enemy lines, Steiner turns to find a young recruit jumping over shafts of light. The recruit explains that it’s a “child’s game”; “it’s bad luck to stand on sunshine”. If he misses the beams they might just all get through all right. Superstitions and childish games act as talismans-charms against death.

The Guardian: Cross of Iron is unusual among second world war movies in that the Germans are the heroes, though it carefully distances its protagonists from actual Nazism. The ordinary soldiers show no interest in politics at all, aside from resentment of their officers. The officers can see that Hitler's disastrous military strategy is losing the war, and are already trying to work out how to play things when it is over. Stransky comes close to master-race theory when he claims that he has "ethical and intellectual superiority" in his blood – but also states firmly that he has never been a Nazi. Instead, he's a Prussian aristocratic supremacist, who disdains the low-born Hitler as readily as he would disdain anyone else who didn't have several pages and a fancy engraving in the Almanach de Gotha. The film's most obvious Nazi is SS recruit Private Zoll (Arthur Brauss), and it's probably not a coincidence that the screenplay reserves for him the stickiest of all its endings.

Slant: Sam Peckinpah’s autumnal battlefield epic deigns to critique unchecked masculinity by pitting two WWII German army den mothers against each other amid the backdrop of their infantry’s retreat from Russian battle lines. Which sort of raises the question whether Peckinpah only felt comfortable taking a more ambivalent view of the sort of six-shooter sensitivity he previously celebrated in The Wild Bunch when the men standing center stage were Nazis, generally portrayed with zee requisite feline silkiness.

NYTimes: Mr. Peckinpah's continuing concern for the corruptibility of children is something, given the once-over-lightly treatment behind the opening credits, which detail the rise and fall of the Nazi war machine, while the rest of the movie is virtually a parody of his machismo themes. "A man is generally what he feels himself to be," says Mr. Coburn at one point, but these characters don't have a convincing feeling among them.

I can't believe that the director ever had his heart in this project, which, from the beginning, looks to have been prepared for the benefit of the people who set off explosives. However, the battle footage is so peculiarly cut into the narrative that you often don't know who is doing what to whom. The visual effect, especially when bodies, buildings and vehicles are blown up in slow motion, becomes as Abstractly Expressionistic as a Jackson Pollock. The blood is thicker than water. It's paint.

Trailer

Full movie on YouTube

Senses of Cinema: When Orson Welles first saw Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron (1977) he cabled Peckinpah that it was the best anti-war film he had ever seen about the “ordinary enlisted man”. Although Peckinpah’s earlier film Major Dundee (1965) deals with some of the ramifications of the US Civil War, Cross of Iron establishes its story firmly in the front line of war, depicting its horrors and the psychological damage it inflicts on its participants. Made in Yugoslavia on a low budget, this sombre and claustrophobic film deals with a German reconnaissance platoon involved in the retreat from the Russian front. A commercial failure in America, it was released in Europe in the spring of 1977 to rave reviews. In Germany it was awarded a Bambi and, ironically, it became the biggest grossing film in Germany and Austria since The Sound of Music (Robert Wise, 1965).

Amongst the mud, slaughter and wreckage, against the endless, harsh, bone-shattering explosions and flashing lights, Steiner attempts to protect the men under his command. Like many of Peckinpah’s protagonists, Steiner is an independent and anarchic character who detests all forms of authority. Although a highly decorated Sergeant, who somehow always manages to cheat death, he detests the uniform he wears and everything it stands for. His nemesis appears in the figure of the oily-haired and pink-cheeked Captain Stransky (Maximillian Schell). A wealthy aristocratic Prussian, Stransky has volunteered for the front with the express aim of winning the “Iron Cross” (awarded to German soldiers for extreme bravery). An increasing animosity develops between the two men with Stransky eventually taking murderous actions. Under his command, Steiner’s platoon is abandoned behind enemy lines, where almost all of them eventually perish.

In some ways, the film’s narrative is of peripheral importance. What it does is mark out situations where psychological dramas and emotive actions can be explored. Even in the context of Peckinpah’s oeuvre this is a film of extreme actions and moments. We see the horrific scars and amputations of wounded soldiers, vehicles drive over dead bodies, silent orgiastic killings take place, anonymous figures are blown to smithereens, and soldiers are shot by their own sides. In this film Peckinpah returns to the explosive sequences of violence that we find in The Wild Bunch (1969); however, he is less concerned with the ecstatic function of violence and more meditative about the characters who participate in its action and whose fates often seem inevitable. A strange complexity and lyricism infuses sequences in which he delves into the function of war and the reasons why men join armies and fight, while surreal, dream-like sequences explore the psychological damage inflicted on these men.

However, in Cross of Iron, as with most of Peckinpah’s films, there is a dual pulse beating. Amongst the destruction, betrayal and violence we also find a humanising love, sensuality and sweetness. Stransky bullies and manipulates a young orderly into confessing that his Captain is homosexual. Stransky then uses this information to blackmail the Captain under threat of banishment and hanging. In Steiner’s bunker, amidst the stench and dirt, his men comfort each other-touch, fondle and hug. Wearing an apron, the group’s scavenger and cook greets a new recruit by blowing him a kiss. The unshaven and scruffy Kruger (Klaus Lowitsch) literally kisses away the rising hysteria in a fellow soldier. The platoon cares for the enemy soldier boy, they have a birthday party, bake a cake, drink, sing and laugh. However, for all the sweetness and dignity that Peckinpah affords Steiner and his soldiers, he appears incapable of viewing female soldiers in the same light. Steiner and his men come across a group of female Russian Soldiers. These women are portrayed as incapable of fair combat, they resort to using their sexuality to trick and cajole Steiner’s men. The misogyny of this sequence is palpable as the female soldiers are ultimately portrayed as a pack of dogs circling helpless prey. Yet women, children, and the notion of home haunt this world of men. While injured in hospital Steiner has an affair with his nurse Eva (Senta Berger). She offers him the possibility of something better-sensuality, beauty and a home. Kruger refuses to wash in the belief that dirt and natural body oils will keep him waterproof. While trying to find their way back through enemy lines, Steiner turns to find a young recruit jumping over shafts of light. The recruit explains that it’s a “child’s game”; “it’s bad luck to stand on sunshine”. If he misses the beams they might just all get through all right. Superstitions and childish games act as talismans-charms against death.

The Guardian: Cross of Iron is unusual among second world war movies in that the Germans are the heroes, though it carefully distances its protagonists from actual Nazism. The ordinary soldiers show no interest in politics at all, aside from resentment of their officers. The officers can see that Hitler's disastrous military strategy is losing the war, and are already trying to work out how to play things when it is over. Stransky comes close to master-race theory when he claims that he has "ethical and intellectual superiority" in his blood – but also states firmly that he has never been a Nazi. Instead, he's a Prussian aristocratic supremacist, who disdains the low-born Hitler as readily as he would disdain anyone else who didn't have several pages and a fancy engraving in the Almanach de Gotha. The film's most obvious Nazi is SS recruit Private Zoll (Arthur Brauss), and it's probably not a coincidence that the screenplay reserves for him the stickiest of all its endings.

Slant: Sam Peckinpah’s autumnal battlefield epic deigns to critique unchecked masculinity by pitting two WWII German army den mothers against each other amid the backdrop of their infantry’s retreat from Russian battle lines. Which sort of raises the question whether Peckinpah only felt comfortable taking a more ambivalent view of the sort of six-shooter sensitivity he previously celebrated in The Wild Bunch when the men standing center stage were Nazis, generally portrayed with zee requisite feline silkiness.

NYTimes: Mr. Peckinpah's continuing concern for the corruptibility of children is something, given the once-over-lightly treatment behind the opening credits, which detail the rise and fall of the Nazi war machine, while the rest of the movie is virtually a parody of his machismo themes. "A man is generally what he feels himself to be," says Mr. Coburn at one point, but these characters don't have a convincing feeling among them.

I can't believe that the director ever had his heart in this project, which, from the beginning, looks to have been prepared for the benefit of the people who set off explosives. However, the battle footage is so peculiarly cut into the narrative that you often don't know who is doing what to whom. The visual effect, especially when bodies, buildings and vehicles are blown up in slow motion, becomes as Abstractly Expressionistic as a Jackson Pollock. The blood is thicker than water. It's paint.

Trailer

Full movie on YouTube

Yeah, I thought of Platoon as well, especially given the bunker scenes early on. They were just one rising shotgun away from being mirrors. Max Schell is such an amazing prick in this! And Jimmy Coburn just burns cool like CNG. And I'll say it again, David Warner dresses up any movie he's in, even ramshackle ones.

Sam Peckinpah, what an amazing fucked-up individual. Quite the artist.

A note, the youtube version seems reveresed, as in all the titles are backwards. I wonder if that means the camera shots are all mirrored?

Great pick, MoonOrb.

posted by valkane at 7:52 AM on May 1, 2016

Sam Peckinpah, what an amazing fucked-up individual. Quite the artist.

A note, the youtube version seems reveresed, as in all the titles are backwards. I wonder if that means the camera shots are all mirrored?

Great pick, MoonOrb.

posted by valkane at 7:52 AM on May 1, 2016

Cross of Iron isn't a Hollywood film, just to make that clear. Pekinpah put some of his own money into it as well, and then had to take a job on Convoy. The opening credit sequence was also done by Pekinpah, after he and James Coburn took a trip to the German archives in Koblenz.

posted by Ideefixe at 2:21 PM on May 1, 2016

posted by Ideefixe at 2:21 PM on May 1, 2016

Thanks for posting this! This movie has a special place in my heart: my best friend and I have adopted "show 'em where the Iron Crosses grow!" as a sort of battle-cry.

posted by orrnyereg at 2:30 AM on May 3, 2016

posted by orrnyereg at 2:30 AM on May 3, 2016

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

Am I reading too much into this? Like I said I haven't seen CoI yet.

posted by Justinian at 6:19 PM on April 30, 2016 [1 favorite]