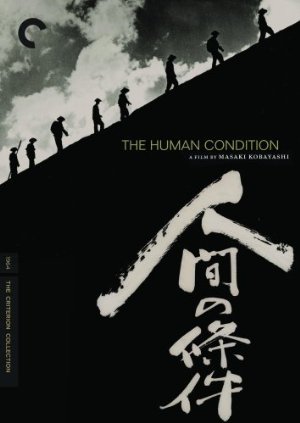

The Human Condition I: No Greater Love (1959)

June 4, 2016 8:06 AM - Subscribe

A Japanese pacifist, unable to face the dire consequences of conscientious objection, is transformed by his attempts to compromise with the demands of war-time Japan.

Slate: The movies focus on Kaji (Japanese icon Tatsuya Nakadai), a self-righteous leftist wanker who becomes, over the course of these three films, one of the most fully realized human beings in cinema, the equivalent of Charles Foster Kaneor Michael Corleone. In the first film, No Greater Love, Kaji's unshakeable belief in the equality of men spawns a report on how to implement more equitable management techniques, which, in turn, earns him a promotion in his company and a chance to put his theory into practice at the Loh Hu Liong iron mines in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. Before leaving, he impulsively marries the long-suffering Michiko and they head north, convinced that Kaji's socialist management style will carry the day.

Not so much. The Loh Hu Liong mine is a tangled nest of black marketers, sadistic overseers, baby-faced owners with murder in their hearts, payoffs, kickbacks, and bribes with the workers encouraged to meet overly ambitious quotas by whip-wielding pit bosses. On top of that, Kaji finds himself managing 60 comfort women who are dropped into the barracks every night as sex toys for the brutalized workers. His delicate sensibilities shredded, Kaji reaches the end credits still hanging on to his humanity, despite some pauses for mass executions and rope bondage at the hands of the military police.

The second film, Road to Eternity, sees Kaji demoted from a boss to a cog in the imperial war machine. An essay on military brutality that makes Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket look like a church picnic, this movie blurs into one long, endless barracks brawl, only coming into focus toward the end as Russian forces approach the Japanese lines like grim death. The finale sees Kaji's human decency hauled out, held down, and forcibly sodomized by the horrors of combat. In No Greater Love, Kaji agonized over how to be good. By the end of Road to Eternity, he growls, "I'm a monster, but I'm going to stay alive."

The third film, A Soldier's Prayer, achieves a bleak grandeur, with Kaji trapped behind enemy lines and leading a band of shell-shocked refugees and deserters on an incredible slog through thousands of miles of enemy territory as they try to get back home to Japan. It kicks off in a haunted forest, comes to a head with an orgy from hell, then wraps up in a Soviet POW camp, where leftist ideology meets Soviet communism in a bone-jarring collision. Kaji still dreams of "[a] better world. Where people are treated like human beings," but he doesn't find it in these films.

NYTimes (A.O. Scott): “The Human Condition” is also, and most memorably, an intimately scaled chronicle of individual experience. Tatsuya Nakadai, who plays its hero, an idealistic technocrat named Kaji, appears in nearly every frame, and it is his deeply personal anguish that provides an emotional anchor for this episodic, theme-heavy story. Mr. Nakadai, one of Japan’s great movie stars of the 1960s (and the subject of a fantastic retrospective at Film Forum that concludes with a three-week run of an immaculate new print of “The Human Condition”), looks a bit like a young Gregory Peck. And in this film he plays, as Peck often did, a liberal man of principle trying to uphold his ideals in difficult circumstances.

Taller than most of the other people in the film, or at least photographed to look that way, Kaji occupies an elevated moral plane as well. In conditions that become, for him and those around him, increasingly harsh and perilous, he insists on doing the right thing and on prevailing by reason rather than by force. As a young manager for a Japanese mining company in Manchuria (then the puppet state of Manchukuo), he writes a report proposing improved conditions for Chinese workers. His boss is a bit skeptical, but nonetheless sends Kaji, along with his adoring wife, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), out to the hinterlands to put his theories into practice.

The mine is both a world unto itself and a microcosm of the larger society, rather like a frontier town in an old western. And Kaji’s experience there, detailed in the epic film’s first and longest part, “No Greater Love,” sets the template for what will follow. In trying to implement basic reforms, he must first deal with the complacency of his superiors and the corruption of the work-gang bosses who control day-to-day underground activity, and then with the harsh, arrogant authoritarianism of the military police, who bring in prisoners of war for slave labor.

Kobayashi, who served in the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II — repeatedly refusing promotion above the rank of private as a form of protest — presents a cleareyed, devastating critique of his country’s military traditions, against which Kaji is ranged in an increasingly lonely and perilous struggle. After his experiment in bringing a measure of decency to the mine ends in personal catastrophe redeemed by a partial moral victory, he is conscripted into the army, where he tries, once again, to bring a measure of fairness and dignity to a system built on the corruption, coercion and the humiliation of the weak.

Slant: Each of Human Condition‘s three sections has similar sets of characters: the vicious enforcer of violent military ethos; the uneasy ally of Kaji’s humanist ideals; the innocent accidentally endangered by Kaji’s well-meaning efforts. If these similarly patterned types, and the conflicts they incite, tend to wear on the viewer, they underline the film’s unswerving vision of the individual’s unending battle with soul-deadening complacency. Kobayashi and cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima similarly return to a collection of recurring images whose meaning shift and expand as the film progresses. Human Condition is filled with groups of people—workers, soldiers, refugees—trudging through barren fields and rocky pathways. Kaji often stands outside such assemblages, signaling both his resistance to conformity and his distance from the very people he seeks to help. Indeed, the film’s most powerful and iconic images cast Kaji as a solitary figure walking alone on an abandoned mountain path or across a desolate plain. Here, Kaji is placed on the horizon line between the empty, shadowy land and the bright, often smoke-shrouded sky: an increasingly isolated man overwhelmed by his own frustrated and divided soul.

It all sounds like a downer, and Human Condition is an indisputably solemn film. Yet it also possesses a restless vitality, with hard cuts juxtaposing abject brutality with pastoral tranquility and romantic longing. Scenes between Kaji and his fretful, yearning wife Michiko (Michiyo Aratama) sometimes fall into domestic melodrama, yet often poignantly convey a loving couple’s struggle to remain connected as professional and personal failings weigh heavier with each passing day. And Kobayashi was certainly rewarded when he cast the relatively new Nakadai in the central role. Without a continually fascinating and empathetic Kaji, Human Condition could have quickly become rote and dreary, even with Kobayashi’s considerable cinematic gifts. Nakadai’s performance burns ever so slowly, with each new humiliation and ethical lapse expressed through glances by turns ravaged, dejected, and stubbornly hopeful. Such moments ground Human Condition‘s grand message in painfully human terms, making this prolonged journey an ultimately enriching and worthwhile one.

Horrible NYTimes Original Review (Bosley Crowther)

Full Movie on YouTube

Part II, The Road To Eternity, on YouTube

Part III, A Soldier's Prayer, on YouTube

Slate: The movies focus on Kaji (Japanese icon Tatsuya Nakadai), a self-righteous leftist wanker who becomes, over the course of these three films, one of the most fully realized human beings in cinema, the equivalent of Charles Foster Kaneor Michael Corleone. In the first film, No Greater Love, Kaji's unshakeable belief in the equality of men spawns a report on how to implement more equitable management techniques, which, in turn, earns him a promotion in his company and a chance to put his theory into practice at the Loh Hu Liong iron mines in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. Before leaving, he impulsively marries the long-suffering Michiko and they head north, convinced that Kaji's socialist management style will carry the day.

Not so much. The Loh Hu Liong mine is a tangled nest of black marketers, sadistic overseers, baby-faced owners with murder in their hearts, payoffs, kickbacks, and bribes with the workers encouraged to meet overly ambitious quotas by whip-wielding pit bosses. On top of that, Kaji finds himself managing 60 comfort women who are dropped into the barracks every night as sex toys for the brutalized workers. His delicate sensibilities shredded, Kaji reaches the end credits still hanging on to his humanity, despite some pauses for mass executions and rope bondage at the hands of the military police.

The second film, Road to Eternity, sees Kaji demoted from a boss to a cog in the imperial war machine. An essay on military brutality that makes Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket look like a church picnic, this movie blurs into one long, endless barracks brawl, only coming into focus toward the end as Russian forces approach the Japanese lines like grim death. The finale sees Kaji's human decency hauled out, held down, and forcibly sodomized by the horrors of combat. In No Greater Love, Kaji agonized over how to be good. By the end of Road to Eternity, he growls, "I'm a monster, but I'm going to stay alive."

The third film, A Soldier's Prayer, achieves a bleak grandeur, with Kaji trapped behind enemy lines and leading a band of shell-shocked refugees and deserters on an incredible slog through thousands of miles of enemy territory as they try to get back home to Japan. It kicks off in a haunted forest, comes to a head with an orgy from hell, then wraps up in a Soviet POW camp, where leftist ideology meets Soviet communism in a bone-jarring collision. Kaji still dreams of "[a] better world. Where people are treated like human beings," but he doesn't find it in these films.

NYTimes (A.O. Scott): “The Human Condition” is also, and most memorably, an intimately scaled chronicle of individual experience. Tatsuya Nakadai, who plays its hero, an idealistic technocrat named Kaji, appears in nearly every frame, and it is his deeply personal anguish that provides an emotional anchor for this episodic, theme-heavy story. Mr. Nakadai, one of Japan’s great movie stars of the 1960s (and the subject of a fantastic retrospective at Film Forum that concludes with a three-week run of an immaculate new print of “The Human Condition”), looks a bit like a young Gregory Peck. And in this film he plays, as Peck often did, a liberal man of principle trying to uphold his ideals in difficult circumstances.

Taller than most of the other people in the film, or at least photographed to look that way, Kaji occupies an elevated moral plane as well. In conditions that become, for him and those around him, increasingly harsh and perilous, he insists on doing the right thing and on prevailing by reason rather than by force. As a young manager for a Japanese mining company in Manchuria (then the puppet state of Manchukuo), he writes a report proposing improved conditions for Chinese workers. His boss is a bit skeptical, but nonetheless sends Kaji, along with his adoring wife, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), out to the hinterlands to put his theories into practice.

The mine is both a world unto itself and a microcosm of the larger society, rather like a frontier town in an old western. And Kaji’s experience there, detailed in the epic film’s first and longest part, “No Greater Love,” sets the template for what will follow. In trying to implement basic reforms, he must first deal with the complacency of his superiors and the corruption of the work-gang bosses who control day-to-day underground activity, and then with the harsh, arrogant authoritarianism of the military police, who bring in prisoners of war for slave labor.

Kobayashi, who served in the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II — repeatedly refusing promotion above the rank of private as a form of protest — presents a cleareyed, devastating critique of his country’s military traditions, against which Kaji is ranged in an increasingly lonely and perilous struggle. After his experiment in bringing a measure of decency to the mine ends in personal catastrophe redeemed by a partial moral victory, he is conscripted into the army, where he tries, once again, to bring a measure of fairness and dignity to a system built on the corruption, coercion and the humiliation of the weak.

Slant: Each of Human Condition‘s three sections has similar sets of characters: the vicious enforcer of violent military ethos; the uneasy ally of Kaji’s humanist ideals; the innocent accidentally endangered by Kaji’s well-meaning efforts. If these similarly patterned types, and the conflicts they incite, tend to wear on the viewer, they underline the film’s unswerving vision of the individual’s unending battle with soul-deadening complacency. Kobayashi and cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima similarly return to a collection of recurring images whose meaning shift and expand as the film progresses. Human Condition is filled with groups of people—workers, soldiers, refugees—trudging through barren fields and rocky pathways. Kaji often stands outside such assemblages, signaling both his resistance to conformity and his distance from the very people he seeks to help. Indeed, the film’s most powerful and iconic images cast Kaji as a solitary figure walking alone on an abandoned mountain path or across a desolate plain. Here, Kaji is placed on the horizon line between the empty, shadowy land and the bright, often smoke-shrouded sky: an increasingly isolated man overwhelmed by his own frustrated and divided soul.

It all sounds like a downer, and Human Condition is an indisputably solemn film. Yet it also possesses a restless vitality, with hard cuts juxtaposing abject brutality with pastoral tranquility and romantic longing. Scenes between Kaji and his fretful, yearning wife Michiko (Michiyo Aratama) sometimes fall into domestic melodrama, yet often poignantly convey a loving couple’s struggle to remain connected as professional and personal failings weigh heavier with each passing day. And Kobayashi was certainly rewarded when he cast the relatively new Nakadai in the central role. Without a continually fascinating and empathetic Kaji, Human Condition could have quickly become rote and dreary, even with Kobayashi’s considerable cinematic gifts. Nakadai’s performance burns ever so slowly, with each new humiliation and ethical lapse expressed through glances by turns ravaged, dejected, and stubbornly hopeful. Such moments ground Human Condition‘s grand message in painfully human terms, making this prolonged journey an ultimately enriching and worthwhile one.

Horrible NYTimes Original Review (Bosley Crowther)

Full Movie on YouTube

Part II, The Road To Eternity, on YouTube

Part III, A Soldier's Prayer, on YouTube

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by CincyBlues at 6:48 PM on June 5, 2016