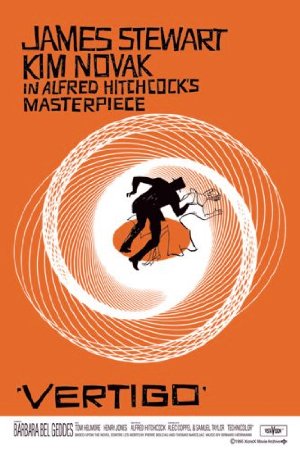

Vertigo (1958)

June 10, 2016 6:45 AM - Subscribe

A San Francisco detective suffering from acrophobia investigates the strange activities of an old friend's wife, all the while becoming dangerously obsessed with her.

NYTimes : You might say that Alfred Hitchcock's latest mystery melodrama, "Vertigo," is all about how a dizzy fellow chases after a dizzy dame, the fellow being an ex-detective and the dame being—well, you guess. That is as fair a thumbnail digest as we can hastily contrive to give you a gist of this picture without giving the secret away. And, believe us, that secret is so clever, even though it is devilishly far-fetched, that we wouldn't want to risk at all disturbing your inevitable enjoyment of the film.

Cinephiliaandbeyond: The most studied and analyzed film of Alfred Hitchcock’s career, Vertigo is on every level a masterclass in filmmaking. In 1958 Hitchcock worked with legendary actor Jimmy Stewart for the fourth and final time, and just like Rear Window, they succeeded in making a film that would enter the history books. We’re talking about a first-class thriller full of labyrinths and dead-ends, an expertly constructed puzzle suspenseful from the first to the last scene, but at the same time, on an entirely different level, it’s a meta-film of sorts, a film about Hitchcock’s filmmaking, a careful and wonderfully elliptic study of the master’s obsession with his female characters.

Hitchcock.tv: Alfred Hitchcock's VERTIGO is a film which functions on multiple levels simultaneously. On a literal level it is a mystery-suspense story of a man hoodwinked into acting as an accomplice in a murder, his discovery of the hoax, and the unraveling of the threads of the murder plot. On a psychological level the film traces the twisted, circuitous routes of a psyche burdened down with guilt, desperately searching for an object on which to concentrate its repressed energy. Finally, on an allegorical or figurative level, it is a retelling of the immemorial tale of a man who has lost his love to death and in hope of redeeming her descends into the underworld, the most famous of these stories being that of Orpheus and Eurydice in Greek Mythology. VERTIGO's complexity, however, does not end with this multilevel approach to its tale; the film also succeeds in blurring the already fine line between objectivity and subjectivity. It takes the viewer so far into the mind of the main character (Scottie, played by Hitchcock veteran James Stewart) that the audience's own objectivity, at least initially, is lost and replaced by complete identification with Scottie's fantasies and obsessions.

Roger Ebert: Then there is another level, beneath all of the others. Alfred Hitchcock was known as the most controlling of directors, particularly when it came to women. The female characters in his films reflected the same qualities over and over again: They were blond. They were icy and remote. They were imprisoned in costumes that subtly combined fashion with fetishism. They mesmerized the men, who often had physical or psychological handicaps. Sooner or later, every Hitchcock woman was humiliated.

“Vertigo” (1958), which is one of the two or three best films Hitchcock ever made, is the most confessional, dealing directly with the themes that controlled his art. It is *about* how Hitchcock used, feared and tried to control women. He is represented by Scottie (James Stewart), a man with physical and mental weaknesses (back problems, fear of heights), who falls obsessively in love with the image of a woman--and not any woman, but the quintessential Hitchcock woman. When he cannot have her, he finds another woman and tries to mold her, dress her, train her, change her makeup and her hair, until she looks like the woman he desires. He cares nothing about the clay he is shaping; he will gladly sacrifice her on the altar of his dreams.

But of course the woman he is shaping and the woman he desires are the same person. Her name is Judy (Kim Novak), and she was hired to play the dream woman, “Madeleine,” as part of a murder plot that Scottie does not even begin to suspect. When he finds out he was tricked, his rage is uncontrollable. He screams out the words: “Did he train you? . . .” Each syllable is a knife in his heart, as he spells out that another man shaped the woman that Scottie thought to shape for himself. The other man has taken not merely Scottie's woman, but Scottie's dream.

That creates a moral paradox at the center of “Vertigo.” The other man (Gavin, played by Tom Helmore) has after all only done to this woman what Scottie also wanted to do. And while the process was happening, the real woman, Judy, transferred her allegiance from Gavin to Scottie, and by the end was not playing her role for money, but as a sacrifice for love.

New Yorker: For Hitchcock, the merest stuff of existence brings inevitable punishment. To exist is to be punished, and, therefore, in God’s just universe, to be guilty—as in the movie that Hitchcock made just prior to “Vertigo,” “The Wrong Man,” in which the protagonist, though innocent of the crime of which he’s wrongly accused, is nonetheless guilty of something. (His appearance of guilt marks, rather, the sin of pride: the belief that one can guard against misfortune through good intentions and good planning). In “Vertigo,” Scotty is, first of all, guilty of not jumping as well as the regular police officer who preceded him across the abyss—the physical man who does his job modestly. Scotty is, rather, is a man out of a place, a lawyer who, dreaming of political power, holds a job for which he’s not quite physically apt. He’s also guilty of an immoderate lust—the plot runs on his old friend Elster’s accurate assumption that Scotty will be quite as turned on by Elster’s mistress as Elster is. (The answer is, more so: he’s so turned on by “Madeleine,” the simulacrum of Elster’s wife, that he doesn’t hesitate to cuckold his friend).

Like Hitchcock himself, Scotty is something of a fetishist; he’s turned on not just by her general beauty but by the particulars of her porcelain blondness and of her severe fashion. And like the viewer himself, Scotty is taken in by the melodramatic acting-out of gothic mumbo-jumbo about the curse of Carlotta Valdes. Kim Novak, as Madeleine, is delivering a terribly overblown performance of an absurd “script,” the one that Elster concocted to lure Scotty to the mission bell tower where the murder plot is to be put into action. In fact, Hitchcock is suggesting that Kim Novak isn’t much more of an actress than Judy Barton—that she even is, in effect, Judy Barton, a country girl who, under the guidance of a master manipulator such as Elster, gets roped into a plot to play platinum blonde and alabaster temptress, and that he himself is Elster, the behind-the-scenes plotter who ropes viewers in (and even turns them on) with a hokey plot and a country girl wearing a lot of makeup.

Slant: Freely adapted from a French novel written in homage to the director himself, the film's dream logic has never cast a universal spell; mulish literalists, whom Hitchcock once bitingly dismissed as “the plausibles,” can endlessly pick apart its convoluted plot, but that's to neglect the prosaic resolution of many of its enigmatic mysteries. Sidelined from police work by a fear of heights, Scottie reluctantly takes a private job from shipbuilder and former college chum Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore, an unsettling cipher) to follow his young wife Madeleine (Novak, a bleached, porcelain icon in her first incarnation). The problem is “not that,” but Elster's suspicion that Madeleine is spellbound or even possessed by the spirit of her Mexican great-grandmother, a mid-19th-century suicide after a sorrowful affair, whose museum portrait and mission grave transfix the gray-suited blonde phantom Scottie trails across the city in long, hypnotic pursuits by car and foot. Once he has to pull his quarry out of the bay after she somnambulantly jumps in, Novak and Stewart share their first dialogue—after Scottie has stripped and dried the unconscious but corporeal specter whose unearthly aura he's succumbed to.

Senses of Cinema: Vertigo does a number of things astoundingly well. The double structure is a stroke of genius, with the film’s first half producing a terribly compelling thriller, and the second opening up Jimmy Stewart’s Scottie in a way that reveals his motivations while illuminating his true colorus. It’s a beautifully shot and composed film, with innumerable visual references to Scottie’s titular vertigo, and breath-taking colour manipulation that pulls you into his tormented head space. Yet at the core of the film sits a love story that, for a modern audience, is virtually impossible to abide. Like so many films from eras past, the “love” in Vertigo is actually just lust and desperation, and like so many anachronistic directors, Hitchcock doesn’t seem to be too concerned about it. This life-changing, world-breaking love between Scottie and Kim Novak’s Madeleine is recklessly shallow, and results in an inevitable cheapening of both characters.

Film Quarterly: But in Vertigo, what is it that we are being asked to look at? “Madeleine” is the general answer to that question, of course, but Madeleine is in fact highly elusive. Even at first sight, Scottie does not see her directly, and after that, he tends to follow her from behind, so that we are only looking at the back of her head—or rather at her hairdo’s black hole. Far from ever satisfying our gaze, Madeleine only entices us into trying to see something else, something in or beyond her, through the alluringly dark telescope embedded in her blonde chignon. We may call that something “Carlotta Valdez,” but Carlotta is also unstable and fleeting; her face in the portrait differs from that of the figure she becomes in Scottie’s nightmare, and in both, her hair is arranged in the same fascinating spiral style.

If the object of our attention is obscure and confused, moreover, so is the narrative logic it normally depends on. For all the garrulity of the exposition, it is never quite clear what following Madeleine is supposed to accomplish. Elster claims that he needs to know where his wife goes before committing her to medical care, but as he seems already well-informed of Madeleine’s unconscious identification with Carlotta, of what possible use to him is the banal list of San Francisco sights that is the only other thing Scottie’s labors turn up? And by the time that Madeleine has jumped into San Francisco Bay, there is surely sufficient evidence to get her to a doctor. Just as the object’s uncertainty implies its ultimate absence, so the plot’s implausibility indicates the motivelessness at its core.

Is Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Vertigo really the best film ever made?

Vertigo Is the New "Greatest Film of All Time"

The Greatest Movies of All Time: Who’s the Victim in ‘Vertigo’?

The Guardian--My favourite Hitchcock: Vertigo

Costume & Identity in Hitchcock’s Vertigo

Trailer

NYTimes : You might say that Alfred Hitchcock's latest mystery melodrama, "Vertigo," is all about how a dizzy fellow chases after a dizzy dame, the fellow being an ex-detective and the dame being—well, you guess. That is as fair a thumbnail digest as we can hastily contrive to give you a gist of this picture without giving the secret away. And, believe us, that secret is so clever, even though it is devilishly far-fetched, that we wouldn't want to risk at all disturbing your inevitable enjoyment of the film.

Cinephiliaandbeyond: The most studied and analyzed film of Alfred Hitchcock’s career, Vertigo is on every level a masterclass in filmmaking. In 1958 Hitchcock worked with legendary actor Jimmy Stewart for the fourth and final time, and just like Rear Window, they succeeded in making a film that would enter the history books. We’re talking about a first-class thriller full of labyrinths and dead-ends, an expertly constructed puzzle suspenseful from the first to the last scene, but at the same time, on an entirely different level, it’s a meta-film of sorts, a film about Hitchcock’s filmmaking, a careful and wonderfully elliptic study of the master’s obsession with his female characters.

Hitchcock.tv: Alfred Hitchcock's VERTIGO is a film which functions on multiple levels simultaneously. On a literal level it is a mystery-suspense story of a man hoodwinked into acting as an accomplice in a murder, his discovery of the hoax, and the unraveling of the threads of the murder plot. On a psychological level the film traces the twisted, circuitous routes of a psyche burdened down with guilt, desperately searching for an object on which to concentrate its repressed energy. Finally, on an allegorical or figurative level, it is a retelling of the immemorial tale of a man who has lost his love to death and in hope of redeeming her descends into the underworld, the most famous of these stories being that of Orpheus and Eurydice in Greek Mythology. VERTIGO's complexity, however, does not end with this multilevel approach to its tale; the film also succeeds in blurring the already fine line between objectivity and subjectivity. It takes the viewer so far into the mind of the main character (Scottie, played by Hitchcock veteran James Stewart) that the audience's own objectivity, at least initially, is lost and replaced by complete identification with Scottie's fantasies and obsessions.

Roger Ebert: Then there is another level, beneath all of the others. Alfred Hitchcock was known as the most controlling of directors, particularly when it came to women. The female characters in his films reflected the same qualities over and over again: They were blond. They were icy and remote. They were imprisoned in costumes that subtly combined fashion with fetishism. They mesmerized the men, who often had physical or psychological handicaps. Sooner or later, every Hitchcock woman was humiliated.

“Vertigo” (1958), which is one of the two or three best films Hitchcock ever made, is the most confessional, dealing directly with the themes that controlled his art. It is *about* how Hitchcock used, feared and tried to control women. He is represented by Scottie (James Stewart), a man with physical and mental weaknesses (back problems, fear of heights), who falls obsessively in love with the image of a woman--and not any woman, but the quintessential Hitchcock woman. When he cannot have her, he finds another woman and tries to mold her, dress her, train her, change her makeup and her hair, until she looks like the woman he desires. He cares nothing about the clay he is shaping; he will gladly sacrifice her on the altar of his dreams.

But of course the woman he is shaping and the woman he desires are the same person. Her name is Judy (Kim Novak), and she was hired to play the dream woman, “Madeleine,” as part of a murder plot that Scottie does not even begin to suspect. When he finds out he was tricked, his rage is uncontrollable. He screams out the words: “Did he train you? . . .” Each syllable is a knife in his heart, as he spells out that another man shaped the woman that Scottie thought to shape for himself. The other man has taken not merely Scottie's woman, but Scottie's dream.

That creates a moral paradox at the center of “Vertigo.” The other man (Gavin, played by Tom Helmore) has after all only done to this woman what Scottie also wanted to do. And while the process was happening, the real woman, Judy, transferred her allegiance from Gavin to Scottie, and by the end was not playing her role for money, but as a sacrifice for love.

New Yorker: For Hitchcock, the merest stuff of existence brings inevitable punishment. To exist is to be punished, and, therefore, in God’s just universe, to be guilty—as in the movie that Hitchcock made just prior to “Vertigo,” “The Wrong Man,” in which the protagonist, though innocent of the crime of which he’s wrongly accused, is nonetheless guilty of something. (His appearance of guilt marks, rather, the sin of pride: the belief that one can guard against misfortune through good intentions and good planning). In “Vertigo,” Scotty is, first of all, guilty of not jumping as well as the regular police officer who preceded him across the abyss—the physical man who does his job modestly. Scotty is, rather, is a man out of a place, a lawyer who, dreaming of political power, holds a job for which he’s not quite physically apt. He’s also guilty of an immoderate lust—the plot runs on his old friend Elster’s accurate assumption that Scotty will be quite as turned on by Elster’s mistress as Elster is. (The answer is, more so: he’s so turned on by “Madeleine,” the simulacrum of Elster’s wife, that he doesn’t hesitate to cuckold his friend).

Like Hitchcock himself, Scotty is something of a fetishist; he’s turned on not just by her general beauty but by the particulars of her porcelain blondness and of her severe fashion. And like the viewer himself, Scotty is taken in by the melodramatic acting-out of gothic mumbo-jumbo about the curse of Carlotta Valdes. Kim Novak, as Madeleine, is delivering a terribly overblown performance of an absurd “script,” the one that Elster concocted to lure Scotty to the mission bell tower where the murder plot is to be put into action. In fact, Hitchcock is suggesting that Kim Novak isn’t much more of an actress than Judy Barton—that she even is, in effect, Judy Barton, a country girl who, under the guidance of a master manipulator such as Elster, gets roped into a plot to play platinum blonde and alabaster temptress, and that he himself is Elster, the behind-the-scenes plotter who ropes viewers in (and even turns them on) with a hokey plot and a country girl wearing a lot of makeup.

Slant: Freely adapted from a French novel written in homage to the director himself, the film's dream logic has never cast a universal spell; mulish literalists, whom Hitchcock once bitingly dismissed as “the plausibles,” can endlessly pick apart its convoluted plot, but that's to neglect the prosaic resolution of many of its enigmatic mysteries. Sidelined from police work by a fear of heights, Scottie reluctantly takes a private job from shipbuilder and former college chum Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore, an unsettling cipher) to follow his young wife Madeleine (Novak, a bleached, porcelain icon in her first incarnation). The problem is “not that,” but Elster's suspicion that Madeleine is spellbound or even possessed by the spirit of her Mexican great-grandmother, a mid-19th-century suicide after a sorrowful affair, whose museum portrait and mission grave transfix the gray-suited blonde phantom Scottie trails across the city in long, hypnotic pursuits by car and foot. Once he has to pull his quarry out of the bay after she somnambulantly jumps in, Novak and Stewart share their first dialogue—after Scottie has stripped and dried the unconscious but corporeal specter whose unearthly aura he's succumbed to.

Senses of Cinema: Vertigo does a number of things astoundingly well. The double structure is a stroke of genius, with the film’s first half producing a terribly compelling thriller, and the second opening up Jimmy Stewart’s Scottie in a way that reveals his motivations while illuminating his true colorus. It’s a beautifully shot and composed film, with innumerable visual references to Scottie’s titular vertigo, and breath-taking colour manipulation that pulls you into his tormented head space. Yet at the core of the film sits a love story that, for a modern audience, is virtually impossible to abide. Like so many films from eras past, the “love” in Vertigo is actually just lust and desperation, and like so many anachronistic directors, Hitchcock doesn’t seem to be too concerned about it. This life-changing, world-breaking love between Scottie and Kim Novak’s Madeleine is recklessly shallow, and results in an inevitable cheapening of both characters.

Film Quarterly: But in Vertigo, what is it that we are being asked to look at? “Madeleine” is the general answer to that question, of course, but Madeleine is in fact highly elusive. Even at first sight, Scottie does not see her directly, and after that, he tends to follow her from behind, so that we are only looking at the back of her head—or rather at her hairdo’s black hole. Far from ever satisfying our gaze, Madeleine only entices us into trying to see something else, something in or beyond her, through the alluringly dark telescope embedded in her blonde chignon. We may call that something “Carlotta Valdez,” but Carlotta is also unstable and fleeting; her face in the portrait differs from that of the figure she becomes in Scottie’s nightmare, and in both, her hair is arranged in the same fascinating spiral style.

If the object of our attention is obscure and confused, moreover, so is the narrative logic it normally depends on. For all the garrulity of the exposition, it is never quite clear what following Madeleine is supposed to accomplish. Elster claims that he needs to know where his wife goes before committing her to medical care, but as he seems already well-informed of Madeleine’s unconscious identification with Carlotta, of what possible use to him is the banal list of San Francisco sights that is the only other thing Scottie’s labors turn up? And by the time that Madeleine has jumped into San Francisco Bay, there is surely sufficient evidence to get her to a doctor. Just as the object’s uncertainty implies its ultimate absence, so the plot’s implausibility indicates the motivelessness at its core.

Is Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Vertigo really the best film ever made?

Vertigo Is the New "Greatest Film of All Time"

The Greatest Movies of All Time: Who’s the Victim in ‘Vertigo’?

The Guardian--My favourite Hitchcock: Vertigo

Costume & Identity in Hitchcock’s Vertigo

Trailer

From Sans Soleil, by Chris Marker (1983):

posted by ubiquity at 10:02 AM on June 10, 2016

I just came in here to say that this is my favourite film. If you ever get a chance to watch it in a theatre do so. The anxious tense energy of Vertigo is so surprising, even if you've seen it before.

posted by Paragon at 11:57 AM on June 10, 2016

posted by Paragon at 11:57 AM on June 10, 2016

My favorite film as well, not just for its locations and beauty and pacing and drama, but for awakening in me the realization that even nice guys like Jimmy Stewart can be obnoxiously oblivious and creepy, and I'd stand a better chance of not being creepy if I made the effort to not be oblivious.

posted by infinitewindow at 1:09 PM on June 10, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by infinitewindow at 1:09 PM on June 10, 2016 [1 favorite]

It's also my favorite movie. It's beautiful and hypnotic and disturbing in all the best ways. It is definitely Bernard Herrmann's best music score.

posted by wabbittwax at 4:54 PM on June 10, 2016

posted by wabbittwax at 4:54 PM on June 10, 2016

I'll be the contrarian here, I guess. I have never been able to like this film. I suppose I'll watch it again to see if I've changed my mind since the last time I saw it but I would be greatly surprised if I had.

Yes, there's some brilliant technical work here -- Hitchcock knows how to use the camera and some of the framing and scene setups are remarkably effective. And Herrmann's score is effective. But the pacing is uneven, the plot is weird and overly contrived, and all of the brilliant filmmaking tricks Hitchcock pulls off are ultimately wasted in the service of a movie that has a hole where its heart should be. The protagonist is creepy and dangerous, the object of his obsession hardly any better, and everything is cold -- the warmth and fun and humor and repartee that hold up the (sometimes equally elaborate) plots of his other films so that you're just too busy having fun to notice that nobody really acts like that simply aren't here and so everything feels off to an extent that is more than I think was intended.

I can recognize that a lot of skill went into making this movie but I still don't get the appeal.

posted by Nerd of the North at 2:28 AM on June 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

Yes, there's some brilliant technical work here -- Hitchcock knows how to use the camera and some of the framing and scene setups are remarkably effective. And Herrmann's score is effective. But the pacing is uneven, the plot is weird and overly contrived, and all of the brilliant filmmaking tricks Hitchcock pulls off are ultimately wasted in the service of a movie that has a hole where its heart should be. The protagonist is creepy and dangerous, the object of his obsession hardly any better, and everything is cold -- the warmth and fun and humor and repartee that hold up the (sometimes equally elaborate) plots of his other films so that you're just too busy having fun to notice that nobody really acts like that simply aren't here and so everything feels off to an extent that is more than I think was intended.

I can recognize that a lot of skill went into making this movie but I still don't get the appeal.

posted by Nerd of the North at 2:28 AM on June 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

I really love this film, despite the contrivances, mainly as the ne plus ultra of High Hitchcock.

Also, a shout out to my favorite character in the film -- Midge, played by Barbara Bel Geddes. She's everything Kim Novak is not: she's an artist, she's obviously intelligent and creative and full of energy, she's practically squirming with sexual frustration and yearning for Scottie. She's the anti-Hitch's Woman, and the fact that she is even in the film speaks to Ebert's anaylsis of the meta-level of the film.

posted by briank at 7:02 AM on June 11, 2016 [7 favorites]

Also, a shout out to my favorite character in the film -- Midge, played by Barbara Bel Geddes. She's everything Kim Novak is not: she's an artist, she's obviously intelligent and creative and full of energy, she's practically squirming with sexual frustration and yearning for Scottie. She's the anti-Hitch's Woman, and the fact that she is even in the film speaks to Ebert's anaylsis of the meta-level of the film.

posted by briank at 7:02 AM on June 11, 2016 [7 favorites]

Yes, hooray for Midge! Successful, talented, funny and not doomed.

posted by roger ackroyd at 8:53 AM on June 11, 2016 [6 favorites]

posted by roger ackroyd at 8:53 AM on June 11, 2016 [6 favorites]

Jimmy Stewart acted in films with BOTH women who played Miss Ellie on Dallas!

posted by Chrysostom at 9:13 AM on June 11, 2016

posted by Chrysostom at 9:13 AM on June 11, 2016

I have slight acrophobia myself, nothing too severe but for I've avoided watching this film for many years, becuase I worry that it'll just bring out some of my own anxiety. It's the one Hitchcock film that I've yet to watch. Should I reconsider? How much does the plot of the film depend on this particular theme?

posted by Fizz at 10:44 AM on June 11, 2016

posted by Fizz at 10:44 AM on June 11, 2016

Fizz, the film opens with a falling death and the protagonist hanging for his life—and we never see how he is saved. If you can get through the first seven minutes after the opening credits, you'll likely be fine.

posted by infinitewindow at 4:36 PM on June 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by infinitewindow at 4:36 PM on June 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

There's a bit at the beginning, there's a bit at the end, a bit with a stepladder towards the beginning and a couple of flashbacks. I'm really fairly acrophobic and it makes me a bit anxious at times, but for me that's part of the price of watching the film. It's not Man on Wire, that's for sure.

It is one of Hitchcock's greatest, and definitely worth seeing. That said, I first saw it when it was re-released in the early 80s: several of Hitchcock's films had been unavailable in the UK for a long time for rights reasons and they were rereleased in pristine prints. I saw Vertigo and Rear Window and I remember being impressed by Vertigo but completely bowled over by Rear Window. I can see why the critics go for it, though.

I'm glad I'm not the only member of the Midge fan club, too.

posted by Grangousier at 4:36 PM on June 11, 2016

It is one of Hitchcock's greatest, and definitely worth seeing. That said, I first saw it when it was re-released in the early 80s: several of Hitchcock's films had been unavailable in the UK for a long time for rights reasons and they were rereleased in pristine prints. I saw Vertigo and Rear Window and I remember being impressed by Vertigo but completely bowled over by Rear Window. I can see why the critics go for it, though.

I'm glad I'm not the only member of the Midge fan club, too.

posted by Grangousier at 4:36 PM on June 11, 2016

I'm so in love with the look of Hitchcock's '50s color films. The widescreen VistaVision combined with the mid-period Technicolor give them such an amazing color palette and scope. He and his cinematographer Robert Burks just jumped into the new format and composed the hell out it. This is a great analysis of the early scene where Scotty gets ensnared in the plot.

posted by octothorpe at 8:38 AM on June 12, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by octothorpe at 8:38 AM on June 12, 2016 [1 favorite]

Just taking a second here to point out that whatever you think of Vertigo, it was integral to both High Anxiety and Twelve Monkeys. For that alone, it wins my undying love.

posted by miss-lapin at 4:59 PM on June 12, 2016

posted by miss-lapin at 4:59 PM on June 12, 2016

Just rewatched it again today for the first time in a while and loved it all over again. The plot only makes any sense if you squint a lot but Hitchcock never cared much about realism.

posted by octothorpe at 5:41 PM on June 12, 2016

posted by octothorpe at 5:41 PM on June 12, 2016

I just came in here to say that this is my favourite film. If you ever get a chance to watch it in a theatre do so. The anxious tense energy of Vertigo is so surprising, even if you've seen it before.

I watched this afternoon in a theatre, and it was the first time in many, many years that I saw it. The second half of the film, where Scottie's obsession is revealed, was marked by titters from the audience when, for example, Scottie demanded that the department store assistants bring out and make alterations to the exact gray suit that Judy had worn as Madeline. Even in 1958, of course, Scottie's controlling behavior was meant to demonstrate the intensity of his obsession; but in 2016, at least the audience I was a part of was not buying that anyone could take seriously a man's demands that he could simply snap his fingers and have a department store order a woman clothes over that woman's objection.

posted by MoonOrb at 4:52 PM on October 23, 2016

I watched this afternoon in a theatre, and it was the first time in many, many years that I saw it. The second half of the film, where Scottie's obsession is revealed, was marked by titters from the audience when, for example, Scottie demanded that the department store assistants bring out and make alterations to the exact gray suit that Judy had worn as Madeline. Even in 1958, of course, Scottie's controlling behavior was meant to demonstrate the intensity of his obsession; but in 2016, at least the audience I was a part of was not buying that anyone could take seriously a man's demands that he could simply snap his fingers and have a department store order a woman clothes over that woman's objection.

posted by MoonOrb at 4:52 PM on October 23, 2016

I guess I've seen this before but remembered almost none of it- watched last night with my 19 year old kid. The color is amazing and San Francisco is absolutely beautiful, but there was a weird way it didn't add up to me. Yes the absurd plot devices are absurd, but also there's a way we have the leads just standing in front of various views of San Francisco that seems, inorganic?

My teen was screaming through every Judy scene about how fucked up Scotty was. Scotty is in fact completely psychotic! I know, times have changed, but just downright hard to watch from today's viewpoint. The funny and dated ideas about psychology were a little wild too. I don't know, a bit of a fable told through melodrama. This is my modern eye watching but I may have been more at ease if it had been a bit more absurd, clarifying the disconnection from reality.

I guess this is just really hard for me to evaluate so far from it's origin.

posted by latkes at 11:38 AM on January 17, 2022

My teen was screaming through every Judy scene about how fucked up Scotty was. Scotty is in fact completely psychotic! I know, times have changed, but just downright hard to watch from today's viewpoint. The funny and dated ideas about psychology were a little wild too. I don't know, a bit of a fable told through melodrama. This is my modern eye watching but I may have been more at ease if it had been a bit more absurd, clarifying the disconnection from reality.

I guess this is just really hard for me to evaluate so far from it's origin.

posted by latkes at 11:38 AM on January 17, 2022

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments