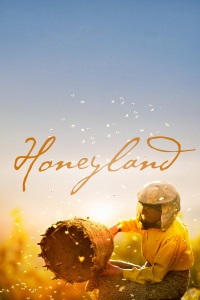

Honeyland (2019)

December 31, 2019 10:43 AM - Subscribe

A woman utilises ancient beekeeping traditions to cultivate honey in the mountains of Macedonia. When a neighbouring family tries to do the same, it becomes a source of tension as they disregard her wisdom and advice. Directed by Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov.

Nestled in an isolated mountain region deep within the Balkans, Hatidze Muratova lives with her ailing mother in a village without roads, electricity or running water. She's the last in a long line of Macedonian wild beekeepers, eking out a living farming honey in small batches to be sold in the closest city -- a mere four hours' walk away. Hatidze's peaceful existence is thrown into upheaval by the arrival of an itinerant family, with their roaring engines, seven rambunctious children and herd of cattle. Hatidze optimistically meets the promise of change with an open heart, offering up her affections, her brandy and her tried-and-true beekeeping advice.It doesn't take long however, before Hussein, the itinerant family's patriarch, senses opportunity and develops an interest in selling his own honey. Hussein has seven young mouths to feed and nowhere to graze his cattle, and he soon casts Hatidze's advice aside in his hunt for profit. This causes a breach in the natural order that provokes a conflict with Hatidze that exposes the fundamental tension between nature and humanity, harmony and discord, exploitation and sustainability. Even as the family provides a much-needed respite from Hatidze's isolation and loneliness, her very means of survival are threatened.

Richard Brody: Yet there is a price—or, perhaps, not a price but merely a needless sacrifice—that comes with tying this mighty narrative knot. Kotevska and Stefanov give little sense of the surrounding world in which the film’s participants live, and what the filmmakers do show tends to frustrate rather than satisfy the viewer’s curiosities. Hatidze travels by train to the country’s capital, Skopje, to sell honey, sitting on the trip, as if by calculated cinematic contrast, next to a teen punk with spiky green hair. Speaking with one of her retailers, who is Albanian, she says that all the other Albanians and Turks have left her village, that she and her mother are the only ones left. But we never find out what kind of crisis or what circumstances led to this exodus, or how isolated Hatidze’s life actually is. (Members of her family are thanked in the film’s credits, but they are never shown onscreen, and it’s never clear whether Hatidze and her mother have any contact with them.) Her life is depicted as one of complete autonomy, as if her rocky corner were long untouched by any civil authority. Yet a scene of great dramatic significance involves the intersection of legal and medical matters, though the filmmakers show no contact between the movie’s subjects and the officials or professionals with whom they’ve apparently had dealings.

Cath Clarke: Honeyland really is a miraculous feat, shot over three years as if by invisible camera – not a single furtive glance is directed towards the film-makers. As for Hatidze, you could watch her for hours. In a heart-tugging scene with one of Hussein’s sons, a favourite of hers, he asks why she didn’t leave the village. “If I had a son like you, it would be different,” she answers. They both look off wistfully, dreaming of another life, a world of harmony.

Helen O'Hara: That comes because of Hussein Sam’s need to provide for his growing family and interest in bee hives, an interest that Hatidze initially encourages with all the enthusiasm of a true afficionado. But he disregards her conservative approach to stewardship and imperils both colonies, creating tension between the neighbours that is as close as we get to a real plot here.

But while there may be small echoes of Jean de Florette’s river, there are no villains here, just people trying to do their best for their families. The filmmakers spent years with their fascinating, complicated heroine and let their images speak for themselves: there are no caption cards here, no narration, just Hatidza’s endlessly expressive face. But the time they lavished on her, and the care and attention they gave to the edit, pays off in intimate storytelling and stunning cinematography.

Trailer

Nestled in an isolated mountain region deep within the Balkans, Hatidze Muratova lives with her ailing mother in a village without roads, electricity or running water. She's the last in a long line of Macedonian wild beekeepers, eking out a living farming honey in small batches to be sold in the closest city -- a mere four hours' walk away. Hatidze's peaceful existence is thrown into upheaval by the arrival of an itinerant family, with their roaring engines, seven rambunctious children and herd of cattle. Hatidze optimistically meets the promise of change with an open heart, offering up her affections, her brandy and her tried-and-true beekeeping advice.It doesn't take long however, before Hussein, the itinerant family's patriarch, senses opportunity and develops an interest in selling his own honey. Hussein has seven young mouths to feed and nowhere to graze his cattle, and he soon casts Hatidze's advice aside in his hunt for profit. This causes a breach in the natural order that provokes a conflict with Hatidze that exposes the fundamental tension between nature and humanity, harmony and discord, exploitation and sustainability. Even as the family provides a much-needed respite from Hatidze's isolation and loneliness, her very means of survival are threatened.

Richard Brody: Yet there is a price—or, perhaps, not a price but merely a needless sacrifice—that comes with tying this mighty narrative knot. Kotevska and Stefanov give little sense of the surrounding world in which the film’s participants live, and what the filmmakers do show tends to frustrate rather than satisfy the viewer’s curiosities. Hatidze travels by train to the country’s capital, Skopje, to sell honey, sitting on the trip, as if by calculated cinematic contrast, next to a teen punk with spiky green hair. Speaking with one of her retailers, who is Albanian, she says that all the other Albanians and Turks have left her village, that she and her mother are the only ones left. But we never find out what kind of crisis or what circumstances led to this exodus, or how isolated Hatidze’s life actually is. (Members of her family are thanked in the film’s credits, but they are never shown onscreen, and it’s never clear whether Hatidze and her mother have any contact with them.) Her life is depicted as one of complete autonomy, as if her rocky corner were long untouched by any civil authority. Yet a scene of great dramatic significance involves the intersection of legal and medical matters, though the filmmakers show no contact between the movie’s subjects and the officials or professionals with whom they’ve apparently had dealings.

Cath Clarke: Honeyland really is a miraculous feat, shot over three years as if by invisible camera – not a single furtive glance is directed towards the film-makers. As for Hatidze, you could watch her for hours. In a heart-tugging scene with one of Hussein’s sons, a favourite of hers, he asks why she didn’t leave the village. “If I had a son like you, it would be different,” she answers. They both look off wistfully, dreaming of another life, a world of harmony.

Helen O'Hara: That comes because of Hussein Sam’s need to provide for his growing family and interest in bee hives, an interest that Hatidze initially encourages with all the enthusiasm of a true afficionado. But he disregards her conservative approach to stewardship and imperils both colonies, creating tension between the neighbours that is as close as we get to a real plot here.

But while there may be small echoes of Jean de Florette’s river, there are no villains here, just people trying to do their best for their families. The filmmakers spent years with their fascinating, complicated heroine and let their images speak for themselves: there are no caption cards here, no narration, just Hatidza’s endlessly expressive face. But the time they lavished on her, and the care and attention they gave to the edit, pays off in intimate storytelling and stunning cinematography.

Trailer

The filmmakers didn’t speak Turkish, and didn’t have translations until they finished shooting, so I don’t think there’s much that was staged for the camera. The cinematographers were Fejmi Daut and Samir Ljuma. Daut does speak Turkish and understood the dialect spoken by Hatizide. The crew shot for about 100 days total, spread out over 3 years.

More info here.

posted by Ideefixe at 12:32 PM on December 31, 2019 [3 favorites]

More info here.

posted by Ideefixe at 12:32 PM on December 31, 2019 [3 favorites]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Carillon at 10:47 AM on December 31, 2019