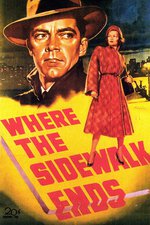

Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950)

March 11, 2016 1:16 AM - Subscribe

Det. Sgt. Mark Dixon wants to be something his old man wasn't: a guy on the right side of the law. But Dixon's vicious nature will get the better of him. Movie found here on YouTube.

Film Noir of the Week: The unpredictable and unfair nature of fate is one strong indicator of film noir. In Where the Sidewalk Ends, there are many occurrences of characters who are tripped up by circumstances beyond their control. The whole movie hinges on Dixon's accidental killing of murder suspect Paine, that only the viewer witnesses. We see Paine lunging first at Dixon, then Dixon reacting by hitting him back only twice - once in the stomach, then again in the face, causing him to fall fatally on his head. How was Dixon to know that Paine has a metal plate in his head? That Dixon finds himself in hot water after showing restraint in his typical violence is the type of sad irony that can only be found in a true film noir.

Slant: Where the Sidewalk Ends‘s optimistic coda is belied by the final sight of a shutting door, a subtle sign that Preminger views such hopeful, redemptive pledges of loyalty and love as denial-fueled fantasies closed off from reality.

Trailers from Hell: Preminger’s camera direction is almost invisible, with the Fox art department making equally undetectable blends between location work and studio shoots. One angle of a taxi pulling up to a building appears to be filmed on the same New York street as the famous shot in Once Upon a Time in America showing a giant bridge stretching out beyond the buildings.

The acting is all smooth and measured, with Dana Andrews once again proving himself the perfect leading man for Otto Preminger. This is also one of Gene Tierney’s better pictures, even though her role is to merely be ladylike and nobly upset through most of the film. It’s amusing that her Morgan Taylor is the daughter of a cab driver, yet carries herself with an elegance of a socialite born into money. Tierney was apparently having romantic difficulties at this time, and I don’t know whether this film came before or after she was sent to London to film Night and the City. Where the Sidewalk Ends is a much better vehicle for her.

Where Danger Lives: The world Preminger depicts here is bleak and gritty, strewn with trash, where predators lurk around the next street corner, and hopelessness blights each back alley. It’s a night-world, as different from the previous Preminger-Andrews project Fallen Angel as it is from Laura. Look in the window of a cheap basement flat and you’ll find Mrs. Tribaum, sleeping the years away at her kitchen table, longing for death to remember her address. Hail a taxi and you’ll meet Jiggs Taylor, who dreams that his fares are dignitaries to be shuttled from one party to the next, so beaten down by a dreary existence that he has trouble separating reality from fantasy, and worships the cop who once used his cab to chase down a petty thief. That clean-cut guy with the dice? That’s Kenneth Paine, an ex-war hero who took off his uniform only to discover that there weren’t any jobs after all, no matter what they said in the Stars and Stripes. Now he’s a degenerate gambler who drinks and smacks his wife.

Senses of Cinema: Sidewalk reflects a specific phase in the development of film noir. Thomas Shatz notes that Hollywood continued to turn out film noir in the early 1950s, including two classics, Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder) and The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston), both made in 1950. However, in spite of this, the big production houses backed away from the social-problem drama, opting for low-budget and low-risk thrillers such as: Panic in the Streets (Elia Kazan, 1950), No Way Out (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) and Sidewalk, avoiding the wrath of conservative critics and social watchdogs. As Paul Schrader establishes, films produced in this period mainly concentrate on the forces of personal disintegration: “After ten years of steadily shedding romantic conventions, the later noir films finally got down to the root causes of the period: the loss of public honor, heroic conventions, personal integrity, and, finally, psychic stability.”

Trailer

Film Noir of the Week: The unpredictable and unfair nature of fate is one strong indicator of film noir. In Where the Sidewalk Ends, there are many occurrences of characters who are tripped up by circumstances beyond their control. The whole movie hinges on Dixon's accidental killing of murder suspect Paine, that only the viewer witnesses. We see Paine lunging first at Dixon, then Dixon reacting by hitting him back only twice - once in the stomach, then again in the face, causing him to fall fatally on his head. How was Dixon to know that Paine has a metal plate in his head? That Dixon finds himself in hot water after showing restraint in his typical violence is the type of sad irony that can only be found in a true film noir.

Slant: Where the Sidewalk Ends‘s optimistic coda is belied by the final sight of a shutting door, a subtle sign that Preminger views such hopeful, redemptive pledges of loyalty and love as denial-fueled fantasies closed off from reality.

Trailers from Hell: Preminger’s camera direction is almost invisible, with the Fox art department making equally undetectable blends between location work and studio shoots. One angle of a taxi pulling up to a building appears to be filmed on the same New York street as the famous shot in Once Upon a Time in America showing a giant bridge stretching out beyond the buildings.

The acting is all smooth and measured, with Dana Andrews once again proving himself the perfect leading man for Otto Preminger. This is also one of Gene Tierney’s better pictures, even though her role is to merely be ladylike and nobly upset through most of the film. It’s amusing that her Morgan Taylor is the daughter of a cab driver, yet carries herself with an elegance of a socialite born into money. Tierney was apparently having romantic difficulties at this time, and I don’t know whether this film came before or after she was sent to London to film Night and the City. Where the Sidewalk Ends is a much better vehicle for her.

Where Danger Lives: The world Preminger depicts here is bleak and gritty, strewn with trash, where predators lurk around the next street corner, and hopelessness blights each back alley. It’s a night-world, as different from the previous Preminger-Andrews project Fallen Angel as it is from Laura. Look in the window of a cheap basement flat and you’ll find Mrs. Tribaum, sleeping the years away at her kitchen table, longing for death to remember her address. Hail a taxi and you’ll meet Jiggs Taylor, who dreams that his fares are dignitaries to be shuttled from one party to the next, so beaten down by a dreary existence that he has trouble separating reality from fantasy, and worships the cop who once used his cab to chase down a petty thief. That clean-cut guy with the dice? That’s Kenneth Paine, an ex-war hero who took off his uniform only to discover that there weren’t any jobs after all, no matter what they said in the Stars and Stripes. Now he’s a degenerate gambler who drinks and smacks his wife.

Senses of Cinema: Sidewalk reflects a specific phase in the development of film noir. Thomas Shatz notes that Hollywood continued to turn out film noir in the early 1950s, including two classics, Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder) and The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston), both made in 1950. However, in spite of this, the big production houses backed away from the social-problem drama, opting for low-budget and low-risk thrillers such as: Panic in the Streets (Elia Kazan, 1950), No Way Out (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) and Sidewalk, avoiding the wrath of conservative critics and social watchdogs. As Paul Schrader establishes, films produced in this period mainly concentrate on the forces of personal disintegration: “After ten years of steadily shedding romantic conventions, the later noir films finally got down to the root causes of the period: the loss of public honor, heroic conventions, personal integrity, and, finally, psychic stability.”

Trailer

« Previous | Club: Film Noir | Next »

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments