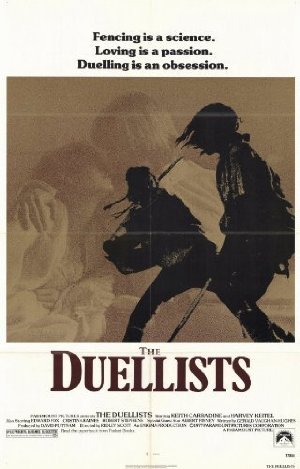

The Duellists (1977)

April 14, 2016 9:56 AM - Subscribe

A duel between two feuding Napoleonic officers eventually evolves into a decades-long series of duels, after each bout - for various reasons - ends unresolved.

NYTimes: The movie, set during the Napoleonic Wars, uses its beauty much in the way that other movies use soundtrack music, to set mood, to complement scenes and even to contradict them. Sometimes it's almost too much, yet the camerawork, which is by Frank Tidy, provides the Baroque style by which the movie operates on our senses, making the eccentric drama at first compelling and ultimately breathtaking.

Slant: Scott adroitly delineates and then suddenly shatters the serenity of the opening's bucolic idyll—exquisitely composed shots of a peasant girl herding geese across verdant pasturelands—when the lass runs headlong into a scowling French soldier who's guarding the perimeter of a duel wherein Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel) skewers the local mayor's son with a foil. (Dueling, we're informed indirectly by subsequent events, was outlawed under Napoleonic law and so had to be carried out in secret.) The scene's abrupt juxtaposition between the beauty of the natural world and the human capacity for bloody violence strikes a chord that resonates throughout The Duellists, from the harsh wintry desolation of the Grand Army's retreat from Moscow, with its bleak vistas of French soldiers frozen into gruesome statuary by an icy death, to the rapturous final shot that finds Feraud standing alone atop a towering massif like an about-to-be-exiled Napoleon contemplating the French countryside laid out before him in all its pastoral splendor.

Deep Focus Reviews: Most memorable is the film’s series of duels, orchestrated by Bill Hobbs and shot with a diversity of styles by its director. A blend of handheld camerawork and tripod shots both place the viewer in the action and establish the formality of the dueling ritual. Violent, clanging swordplay performed with steel blades is jarringly real, as the actors carried out these scenes not with artificial weapons but with blunted edges on actual swords and no button to dull the point. Hobbs’ choreography ensured the actors didn’t kill each other, but the very real threat of death in a possible accident enhanced both central performances. Carradine was versed in fencing but Keitel had never held a sword; as a result, the intense Mean Streets (1973) actor often lost himself in the moment and stepped outside of his marks, forcing Carradine to improvise his swordplay within the scene if only out of self-preservation. Hobbs’ attention to detail and historical research into the art of dueling offers battles that look unlike any other screen duels, with actors wearing the period’s long braids of hair down their cheeks to protect their faces from their opponent’s blade. D’Hubert and Feraud occupy stances authentic to the period, but to viewers accustomed to typical movie duels that use a more rigid formal posture, the bending martial arts poses held by Carradine and Keitel may look strange. Consequently, each distinct duel is more fascinating than the last.

AV Club: As with most Conrad stories, this one is both broadly sketchy and thematically rich, though there's not really enough of it to fill 100 minutes–even with the frail subplot about Carradine's decade-long infatuation with the world-weary Diana Quick. But in spite of the material's thinness, and even though Carradine and Keitel look ridiculous sporting fancy duds while speaking bodice-ripper dialogue in flat American accents, The Duellists endures as a diverting action potboiler. Credit Scott's direction: Emerging from a successful advertising career, he picked an ideal property for a first film, one packed with opportunities for stylish setpieces. He stages each duel distinctively, sometimes framing the action straight-ahead, sometimes making more of the misty locations than the figures within them, and sometimes trimming the fighting to nothing while cutting rapidly between the preparation and the aftermath. Scott's command of pacing and mood led immediately to his 1979 work at the helm of Alien, which in turn kicked off a mostly successful career.

Trailer

Ridley Scott's Brilliant First Film

NYTimes: The movie, set during the Napoleonic Wars, uses its beauty much in the way that other movies use soundtrack music, to set mood, to complement scenes and even to contradict them. Sometimes it's almost too much, yet the camerawork, which is by Frank Tidy, provides the Baroque style by which the movie operates on our senses, making the eccentric drama at first compelling and ultimately breathtaking.

Slant: Scott adroitly delineates and then suddenly shatters the serenity of the opening's bucolic idyll—exquisitely composed shots of a peasant girl herding geese across verdant pasturelands—when the lass runs headlong into a scowling French soldier who's guarding the perimeter of a duel wherein Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel) skewers the local mayor's son with a foil. (Dueling, we're informed indirectly by subsequent events, was outlawed under Napoleonic law and so had to be carried out in secret.) The scene's abrupt juxtaposition between the beauty of the natural world and the human capacity for bloody violence strikes a chord that resonates throughout The Duellists, from the harsh wintry desolation of the Grand Army's retreat from Moscow, with its bleak vistas of French soldiers frozen into gruesome statuary by an icy death, to the rapturous final shot that finds Feraud standing alone atop a towering massif like an about-to-be-exiled Napoleon contemplating the French countryside laid out before him in all its pastoral splendor.

Deep Focus Reviews: Most memorable is the film’s series of duels, orchestrated by Bill Hobbs and shot with a diversity of styles by its director. A blend of handheld camerawork and tripod shots both place the viewer in the action and establish the formality of the dueling ritual. Violent, clanging swordplay performed with steel blades is jarringly real, as the actors carried out these scenes not with artificial weapons but with blunted edges on actual swords and no button to dull the point. Hobbs’ choreography ensured the actors didn’t kill each other, but the very real threat of death in a possible accident enhanced both central performances. Carradine was versed in fencing but Keitel had never held a sword; as a result, the intense Mean Streets (1973) actor often lost himself in the moment and stepped outside of his marks, forcing Carradine to improvise his swordplay within the scene if only out of self-preservation. Hobbs’ attention to detail and historical research into the art of dueling offers battles that look unlike any other screen duels, with actors wearing the period’s long braids of hair down their cheeks to protect their faces from their opponent’s blade. D’Hubert and Feraud occupy stances authentic to the period, but to viewers accustomed to typical movie duels that use a more rigid formal posture, the bending martial arts poses held by Carradine and Keitel may look strange. Consequently, each distinct duel is more fascinating than the last.

AV Club: As with most Conrad stories, this one is both broadly sketchy and thematically rich, though there's not really enough of it to fill 100 minutes–even with the frail subplot about Carradine's decade-long infatuation with the world-weary Diana Quick. But in spite of the material's thinness, and even though Carradine and Keitel look ridiculous sporting fancy duds while speaking bodice-ripper dialogue in flat American accents, The Duellists endures as a diverting action potboiler. Credit Scott's direction: Emerging from a successful advertising career, he picked an ideal property for a first film, one packed with opportunities for stylish setpieces. He stages each duel distinctively, sometimes framing the action straight-ahead, sometimes making more of the misty locations than the figures within them, and sometimes trimming the fighting to nothing while cutting rapidly between the preparation and the aftermath. Scott's command of pacing and mood led immediately to his 1979 work at the helm of Alien, which in turn kicked off a mostly successful career.

Trailer

Ridley Scott's Brilliant First Film

It's been awhile, but I remember seeing this on Z channel when I was a kid, and I really loved it.

posted by homunculus at 7:46 PM on April 14, 2016

posted by homunculus at 7:46 PM on April 14, 2016

I love the attention to the changes in the Hussars' uniform designs from the post-Revolutionary to the Napoleonic period and after. Luckily there is a lot of historical documentation on this, but they really nail the different styles of shako, tassles, ornaments, etc.

posted by TheWhiteSkull at 1:57 PM on April 15, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by TheWhiteSkull at 1:57 PM on April 15, 2016 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

One of the things that really make it for me is that is really uses the irascibility of Keitel to fantastic effect. He essentially personifies one of those people you meet in life who are just massive arseholes, he doesn't feel like he's playing an arsehole, his character just is a natural born dick, but all while resembling an actual human being. The fact that the character exists in a world where he can try and kill you makes me really empathise with the protagonist. The pacing is good, the recreation of the world is convincing despite what I assume was a small budget. I am surprised we don't hear more about this, its a really well made movie.

posted by biffa at 10:44 AM on April 14, 2016 [3 favorites]