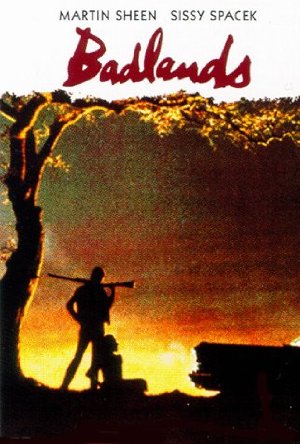

Badlands (1973)

April 16, 2016 8:23 PM - Subscribe

An impressionable teen girl from a dead-end town and her older greaser boyfriend go on a killing spree in the South Dakota badlands.

NYTimes: Badlands inevitably invites comparisons with three other important American films, Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde and Fritz Lang's Fury and You Only Live Once, but it has a very different vision of violence and death. Malick spends no great amount of time invoking Freud to explain the behavior of Kit and Holly, nor is there any Depression to be held ultimately responsible. Society is, if anything, benign.

This is the haunting truth of Badlands, something that places it very much in the seventies in spite of its carefully re-created period detail. Kit and Holly are directionless creatures, technically literate but uneducated in any real sense, so desensitized that Kit (in Malick's words at a news conference) can regard the gun with which he shoots people as a kind of magic wand that eliminates small nuisances. Kit and Holly are members of the television generation run amok.

They are not ill-housed, ill-clothed, or ill-fed. If they are at all aware of their anger (and I'm not sure they are, since they see only boredom), it's because of the difference between the way life is and the way it is presented on the small screen, with commercial breaks instead of lasting consequences.

Movie Mezzanine: What made Badlands truly revolutionary for its time was its depictions of the killer-couple in question. A somewhat similar film was released six years earlier, and is also a revolutionary cultural landmark: Bonnie and Clyde. In that film, the titular protagonists were undoubtedly meant to be antiheroes, and their actions were always shown with a sense of malice. Even if the characters didn’t know that their actions were morally wrong, the film certainly did.

It’s interesting to compare it to Badlands in that sense, because when we see Kit and Holly offing all sorts of people in their cross-country road-trip (in fairly gruesome detail for its time), the violence feels completely and utterly cold and strangely hollow. Perhaps it felt shocking at the time of its release, but today it carries no weight, which is exactly the point. The film is so concerned with Kit and Holly’s affair that the various murders surrounding them are seen merely as inconveniences. Adding to this sense of detachment is the film’s depiction of Kit, who’s so gosh darn likable and charming that you can’t seem to help but root for him even when he constantly does the wrong thing.

Roger Ebert: Their shallowness is in conflict with their deadliness. A friend of Kit’s, who seems to help them but then runs for a phone, is shot in the stomach and left to sit, dazed, dying and contemplative. He’d attempted to lure them into a field with a tale of treasure. That Kit believed him took childlike credulity. A family is killed for no other reason than that Kit and Holly come across their farmhouse. A rich man is spared for no reason at all, and Kit later observes how lucky he was. He uses the man’s Dictaphone to record a fatuous final statement: “Listen to your parents and teachers. They got a line on most things, so don’t treat ‘em like enemies. There’s always an outside chance you can learn something. Try to keep an open mind.” He thinks that because he’s famous, his words have meaning.

Globe and Mail: Although audiences were well-conditioned to the lovers-on-the-lam scenario, a road movie subgenre that dated back at least to Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once and ignited a countercultural sensation just seven years previously with Bonnie and Clyde, Malick’s version was something new and possibly even more unsettling.

For Kit and Holly’s actions couldn’t be written off as the result of poverty, institutional indifference, social pressures, elder generation insensitivity or any such external convenience. When Kit kills Holly’s father (Warren Oates) with a bullet to the back in the man’s own living room, it’s clear he’s done so as a matter of choice, a statement of style and a gesture of pure convenience. But it’s also an invitation to Holly to join in the movie he’s just got rolling for them both, and her expression of inscrutable blankness over the act – our first indication that the casting of the largely unknown Spacek was a stroke of inspiration – suggests both that she’s ready to take her part and to play the supportive audience. This is murder as a role-playing game. This is a movie about living in a movie.

Slant: Badlands is perhaps most different from the rest of Malick's oeuvre in its straightforward narrative continuity and reliance on scenes that play out in real time. With the exception of the ambiguous elliptical nature of the montage-like establishment of Kit and Holly's budding romance, the rest of the film clearly plays out over the course of a week, not unlike the real-life affair between Starkweather and Fugate. Such linear protraction for a filmmaker renowned for lyrical, elliptical filmmaking is perhaps the fledgling of a young film writer discovering his own cinematic framework, and this is sometimes used as an argument against the supposed lack of poeticism and refinement in Malick's first work. But such assumptions about the so-called creative “progression” of an auteur typically denigrates the actual beauty of the film in question. Badlands may not be Malick's best film, but it's certainly his most anomalous, and, therefore, distinct—though The Tree of Life now offers a worthy competitor. Where it's not refined in form, Badlands is so by virtue of the specificity of its material (the then-topical sensationalism of teenage sociopaths and their glamorization in popular culture), a fact that has been buried by the dense literature published on Malick. Yet the film never once feels like the faded photos Holly examines under her father's stereopticon. Badlands can't be classified a historical document awaiting some kind of cultural preservation or renewed interest. It's the beloved little sister in a family teeming with geniuses, yet it's unfortunate that so few critics are compelled to call to attention to her sheer timelessness and sublime character.

Film School Rejects: 7 scenes we love from 'Badlands'

'Badlands': An Oral History

How Terrence Malick's 'Badlands' Addresses the Root Causes of American Gun Violence

How to Shoot a Serial Killer

Trailer

NYTimes: Badlands inevitably invites comparisons with three other important American films, Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde and Fritz Lang's Fury and You Only Live Once, but it has a very different vision of violence and death. Malick spends no great amount of time invoking Freud to explain the behavior of Kit and Holly, nor is there any Depression to be held ultimately responsible. Society is, if anything, benign.

This is the haunting truth of Badlands, something that places it very much in the seventies in spite of its carefully re-created period detail. Kit and Holly are directionless creatures, technically literate but uneducated in any real sense, so desensitized that Kit (in Malick's words at a news conference) can regard the gun with which he shoots people as a kind of magic wand that eliminates small nuisances. Kit and Holly are members of the television generation run amok.

They are not ill-housed, ill-clothed, or ill-fed. If they are at all aware of their anger (and I'm not sure they are, since they see only boredom), it's because of the difference between the way life is and the way it is presented on the small screen, with commercial breaks instead of lasting consequences.

Movie Mezzanine: What made Badlands truly revolutionary for its time was its depictions of the killer-couple in question. A somewhat similar film was released six years earlier, and is also a revolutionary cultural landmark: Bonnie and Clyde. In that film, the titular protagonists were undoubtedly meant to be antiheroes, and their actions were always shown with a sense of malice. Even if the characters didn’t know that their actions were morally wrong, the film certainly did.

It’s interesting to compare it to Badlands in that sense, because when we see Kit and Holly offing all sorts of people in their cross-country road-trip (in fairly gruesome detail for its time), the violence feels completely and utterly cold and strangely hollow. Perhaps it felt shocking at the time of its release, but today it carries no weight, which is exactly the point. The film is so concerned with Kit and Holly’s affair that the various murders surrounding them are seen merely as inconveniences. Adding to this sense of detachment is the film’s depiction of Kit, who’s so gosh darn likable and charming that you can’t seem to help but root for him even when he constantly does the wrong thing.

Roger Ebert: Their shallowness is in conflict with their deadliness. A friend of Kit’s, who seems to help them but then runs for a phone, is shot in the stomach and left to sit, dazed, dying and contemplative. He’d attempted to lure them into a field with a tale of treasure. That Kit believed him took childlike credulity. A family is killed for no other reason than that Kit and Holly come across their farmhouse. A rich man is spared for no reason at all, and Kit later observes how lucky he was. He uses the man’s Dictaphone to record a fatuous final statement: “Listen to your parents and teachers. They got a line on most things, so don’t treat ‘em like enemies. There’s always an outside chance you can learn something. Try to keep an open mind.” He thinks that because he’s famous, his words have meaning.

Globe and Mail: Although audiences were well-conditioned to the lovers-on-the-lam scenario, a road movie subgenre that dated back at least to Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once and ignited a countercultural sensation just seven years previously with Bonnie and Clyde, Malick’s version was something new and possibly even more unsettling.

For Kit and Holly’s actions couldn’t be written off as the result of poverty, institutional indifference, social pressures, elder generation insensitivity or any such external convenience. When Kit kills Holly’s father (Warren Oates) with a bullet to the back in the man’s own living room, it’s clear he’s done so as a matter of choice, a statement of style and a gesture of pure convenience. But it’s also an invitation to Holly to join in the movie he’s just got rolling for them both, and her expression of inscrutable blankness over the act – our first indication that the casting of the largely unknown Spacek was a stroke of inspiration – suggests both that she’s ready to take her part and to play the supportive audience. This is murder as a role-playing game. This is a movie about living in a movie.

Slant: Badlands is perhaps most different from the rest of Malick's oeuvre in its straightforward narrative continuity and reliance on scenes that play out in real time. With the exception of the ambiguous elliptical nature of the montage-like establishment of Kit and Holly's budding romance, the rest of the film clearly plays out over the course of a week, not unlike the real-life affair between Starkweather and Fugate. Such linear protraction for a filmmaker renowned for lyrical, elliptical filmmaking is perhaps the fledgling of a young film writer discovering his own cinematic framework, and this is sometimes used as an argument against the supposed lack of poeticism and refinement in Malick's first work. But such assumptions about the so-called creative “progression” of an auteur typically denigrates the actual beauty of the film in question. Badlands may not be Malick's best film, but it's certainly his most anomalous, and, therefore, distinct—though The Tree of Life now offers a worthy competitor. Where it's not refined in form, Badlands is so by virtue of the specificity of its material (the then-topical sensationalism of teenage sociopaths and their glamorization in popular culture), a fact that has been buried by the dense literature published on Malick. Yet the film never once feels like the faded photos Holly examines under her father's stereopticon. Badlands can't be classified a historical document awaiting some kind of cultural preservation or renewed interest. It's the beloved little sister in a family teeming with geniuses, yet it's unfortunate that so few critics are compelled to call to attention to her sheer timelessness and sublime character.

Film School Rejects: 7 scenes we love from 'Badlands'

'Badlands': An Oral History

How Terrence Malick's 'Badlands' Addresses the Root Causes of American Gun Violence

How to Shoot a Serial Killer

Trailer

When I watched Badlands a handful of years ago, it struck me how much Natural Born Killers owes to it.

Badlands is far the better of the two movies.

True Romance has a piece of score obviously patterned after a music cue from Badlands, too.

posted by Mister Moofoo at 11:26 PM on April 16, 2016

Badlands is far the better of the two movies.

True Romance has a piece of score obviously patterned after a music cue from Badlands, too.

posted by Mister Moofoo at 11:26 PM on April 16, 2016

I liked this way more than I expected to! Both Sheen and Spacek were excellent.

The more I catch up on older films and westerns and the like the less I think of anything Tarantino's touches.

posted by iamkimiam at 1:49 PM on August 12, 2020

The more I catch up on older films and westerns and the like the less I think of anything Tarantino's touches.

posted by iamkimiam at 1:49 PM on August 12, 2020

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by rhizome at 8:57 PM on April 16, 2016