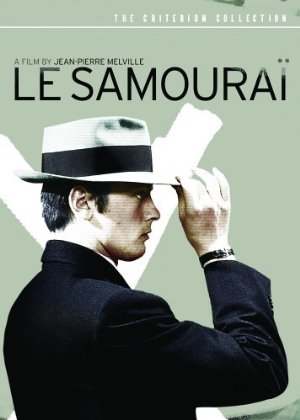

Le Samourai (1967)

May 27, 2016 7:36 PM - Subscribe

After killing a night-club owner, professional hitman Jef Costello is seen by witnesses. His efforts to provide himself with an alibi fail and more and more he gets driven into a corner.

Senses of Cinema: The product of a series of international cinematic exchanges, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï is a perfect example of the geographically and temporally confused nature of cinephilia: 1) In the pre- and post-World War II years European émigré filmmakers brought German Expressionism to the US, laying down the foundations of American film noir, which in turn informed the development of the French New Wave, specifically the genre of the “film policier” (commonly contracted as “polar”); both French New Wavers and Japanese directors, particularly Kurosawa and Suzuki, paid tributes to American gangster/noir films (Godard’s Breathless, 1959, Kurosawa’s High and Low, 1963, Suzuki’s Branded to Kill, 1967) while French filmmakers incorporated motifs from Japanese cinema (for example, Kobayashi’s Seppuku, 1962, along with numerous others, and Melville’s Le Samouraï figure ritualistic suicide); 2) The American western, particularly those of John Ford, was appropriated and reworked into Japanese samurai films (e.g. Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai, 1954); 3) The French New Wave, and European art cinema more generally, influenced both the Hollywood Renaissance of the mid-1960s to late 1970s (e.g. Le Samouraï anticipates Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, 1976) and Hong Kong action cinema (John Woo’s The Killer, 1989, is a loose remake of Le Samouraï).

Although the development of the French polar depended on the adoption and reworking of American film noir – distinguished by its preoccupation with the criminal underworld, eroticised violence, existential angst, paranoia, death, exotic non-white characters, moral ambiguity, and urban nocturnal settings – the gangster/noir genre was not completely new to French cinema: its forerunners include Louis Feuillade’s crime series Les Vampires (1915) and 1930s French poetic realist films featuring doomed working class male protagonists, who eventually became assimilated into the gangster class of the 1950s (1) in films like Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), Dassin’s Du Rififi chez les hommes (1955), Breathless, and Melville’s own Bob le flambeur (1955), Le Doulos (1962), and Le Deuxième souffle (1966). These films anticipated the development of a two-way system of exchange between French and American cinema, with French filmmakers giving the noir genre a specifically French twist (e.g. the portrayal of the femme fatale – Valérie – in Le Samouraï as kind, alluring and mysterious, rather than psychotic, conniving, and double-crossing, or the infantilisation of the femme fatale and the probing of female identity, sexuality and memory in Luc Besson’s polar Nikita, 1990) and, in turn, influencing the development of American neo-noir: Le Samouraï partly inspired Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994)

Roger Ebert: Like a painter or a musician, a filmmaker can suggest complete mastery with just a few strokes. Jean-Pierre Melville involves us in the spell of "Le Samourai" (1967) before a word is spoken. He does it with light: a cold light, like dawn on an ugly day. And color: grays and blues. And actions that speak in place of words.

The Guardian: It gave Alain Delon his best part. Filmed on the wide screen and in wonderfully muted colour to add atmosphere - the great Henri Decaë was Melville's cinematographer - it has Delon as a ruthless hired killer living alone in a dingy apartment with a bullfinch as his sole companion. The girl who loves him (Nathalie Delon, Alain's wife) lives in greater luxury elsewhere at another man's expense and is prepared to give him a perfect alibi after his next contract. He executes it with chilling skill in a nightclub and successfully avoids a hood sent to kill him and a posse of police on his trail.

He is, however, doomed from the first, or, as Melville puts it, "laid out in death". He is tempted by a girl he saw in a corridor of the nightclub and should have killed as a witness; thus he breaks the first rule of his trade, which is not to get emotionally involved. It's a bad mistake and honour demands that she has to be his next contract. But, almost masochistically, he deliberately uses an empty gun and is shot down by the police. He has virtually committed hari-kiri.

Slant: Such a dreamlike aura is amplified by Delon, whose piercingly vacant blue eyes and rigid, expressionless countenance radiate ghostly emptiness and a fatalistic resignation to the unalterable nature of life. A jarring mixture of feminine beauty (his skin and features almost as porcelain-delicate as his spouse’s) and no-nonsense toughness always lay at the heart of Delon’s appeal, and here, his near-total silence shifts the burden of his poised performance onto his simultaneously refined and rough mannerisms. When coupled with Melville’s entrancing mise-en-scène and François de Roubaix’s sweetly melancholic (and seldom used) theme music, Delon’s bordering-on-comical solemnity (enhanced by his unflashy ‘40s-era fedora and trenchcoat) generates a mood of romantic pessimism that speaks to the genre’s characteristic hopelessness. Jef’s emotionless demeanor and reflexive actions are those of a man—or a samurai, as Melville’s title and intro text from the (purely fictional) Bushido: Book of the Samurai implies—who sustains (and gains some modicum of control over) himself via formulaic, dispassionate procedure. And thus Jef’s ultimate doom is set in stone the moment he unwisely spares the sole witness to the crime—a pianist (Cathy Rosier) at the club whose selfless kindness proves fatally intriguing to Jef—a deviation from his masculine code of conduct that marks him as another of noir’s myriad antiheroes who foolishly attempt to stray from their life’s path.

Opening Shots-Le Samourai

The Cinetourist: Le Samourai Places and Maps

Vimeo video essay

Trailer

Senses of Cinema: The product of a series of international cinematic exchanges, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï is a perfect example of the geographically and temporally confused nature of cinephilia: 1) In the pre- and post-World War II years European émigré filmmakers brought German Expressionism to the US, laying down the foundations of American film noir, which in turn informed the development of the French New Wave, specifically the genre of the “film policier” (commonly contracted as “polar”); both French New Wavers and Japanese directors, particularly Kurosawa and Suzuki, paid tributes to American gangster/noir films (Godard’s Breathless, 1959, Kurosawa’s High and Low, 1963, Suzuki’s Branded to Kill, 1967) while French filmmakers incorporated motifs from Japanese cinema (for example, Kobayashi’s Seppuku, 1962, along with numerous others, and Melville’s Le Samouraï figure ritualistic suicide); 2) The American western, particularly those of John Ford, was appropriated and reworked into Japanese samurai films (e.g. Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai, 1954); 3) The French New Wave, and European art cinema more generally, influenced both the Hollywood Renaissance of the mid-1960s to late 1970s (e.g. Le Samouraï anticipates Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, 1976) and Hong Kong action cinema (John Woo’s The Killer, 1989, is a loose remake of Le Samouraï).

Although the development of the French polar depended on the adoption and reworking of American film noir – distinguished by its preoccupation with the criminal underworld, eroticised violence, existential angst, paranoia, death, exotic non-white characters, moral ambiguity, and urban nocturnal settings – the gangster/noir genre was not completely new to French cinema: its forerunners include Louis Feuillade’s crime series Les Vampires (1915) and 1930s French poetic realist films featuring doomed working class male protagonists, who eventually became assimilated into the gangster class of the 1950s (1) in films like Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), Dassin’s Du Rififi chez les hommes (1955), Breathless, and Melville’s own Bob le flambeur (1955), Le Doulos (1962), and Le Deuxième souffle (1966). These films anticipated the development of a two-way system of exchange between French and American cinema, with French filmmakers giving the noir genre a specifically French twist (e.g. the portrayal of the femme fatale – Valérie – in Le Samouraï as kind, alluring and mysterious, rather than psychotic, conniving, and double-crossing, or the infantilisation of the femme fatale and the probing of female identity, sexuality and memory in Luc Besson’s polar Nikita, 1990) and, in turn, influencing the development of American neo-noir: Le Samouraï partly inspired Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994)

Roger Ebert: Like a painter or a musician, a filmmaker can suggest complete mastery with just a few strokes. Jean-Pierre Melville involves us in the spell of "Le Samourai" (1967) before a word is spoken. He does it with light: a cold light, like dawn on an ugly day. And color: grays and blues. And actions that speak in place of words.

The Guardian: It gave Alain Delon his best part. Filmed on the wide screen and in wonderfully muted colour to add atmosphere - the great Henri Decaë was Melville's cinematographer - it has Delon as a ruthless hired killer living alone in a dingy apartment with a bullfinch as his sole companion. The girl who loves him (Nathalie Delon, Alain's wife) lives in greater luxury elsewhere at another man's expense and is prepared to give him a perfect alibi after his next contract. He executes it with chilling skill in a nightclub and successfully avoids a hood sent to kill him and a posse of police on his trail.

He is, however, doomed from the first, or, as Melville puts it, "laid out in death". He is tempted by a girl he saw in a corridor of the nightclub and should have killed as a witness; thus he breaks the first rule of his trade, which is not to get emotionally involved. It's a bad mistake and honour demands that she has to be his next contract. But, almost masochistically, he deliberately uses an empty gun and is shot down by the police. He has virtually committed hari-kiri.

Slant: Such a dreamlike aura is amplified by Delon, whose piercingly vacant blue eyes and rigid, expressionless countenance radiate ghostly emptiness and a fatalistic resignation to the unalterable nature of life. A jarring mixture of feminine beauty (his skin and features almost as porcelain-delicate as his spouse’s) and no-nonsense toughness always lay at the heart of Delon’s appeal, and here, his near-total silence shifts the burden of his poised performance onto his simultaneously refined and rough mannerisms. When coupled with Melville’s entrancing mise-en-scène and François de Roubaix’s sweetly melancholic (and seldom used) theme music, Delon’s bordering-on-comical solemnity (enhanced by his unflashy ‘40s-era fedora and trenchcoat) generates a mood of romantic pessimism that speaks to the genre’s characteristic hopelessness. Jef’s emotionless demeanor and reflexive actions are those of a man—or a samurai, as Melville’s title and intro text from the (purely fictional) Bushido: Book of the Samurai implies—who sustains (and gains some modicum of control over) himself via formulaic, dispassionate procedure. And thus Jef’s ultimate doom is set in stone the moment he unwisely spares the sole witness to the crime—a pianist (Cathy Rosier) at the club whose selfless kindness proves fatally intriguing to Jef—a deviation from his masculine code of conduct that marks him as another of noir’s myriad antiheroes who foolishly attempt to stray from their life’s path.

Opening Shots-Le Samourai

The Cinetourist: Le Samourai Places and Maps

Vimeo video essay

Trailer

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

I find this movie fascinating, but I've also always felt that the critical attempt to impose some kind of elaborate "code" on Jef is an overreach. Taken as a study of masculine honor/ethics, it doesn't make a lot of sense.

posted by praemunire at 9:01 AM on April 14, 2024 [1 favorite]