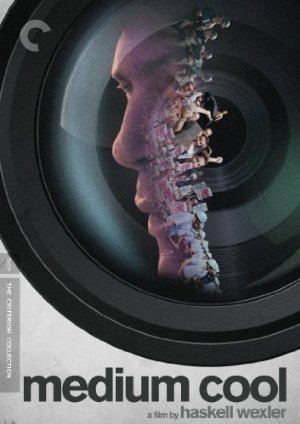

Medium Cool (1969)

May 29, 2016 2:53 PM - Subscribe

A TV news reporter finds himself becoming personally involved in the violence that erupts around the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Slant: Taking its name from the McLuhanist barometer of hot/cool media, Medium Cool analyzes the potential of television. “Medium cool” works as a pun, pointing at once to McLuhan's diagnosis of TV as a passive, “cool” medium, one that “requires a higher sensory involvement from the user,” as well as to the latent possibility for TV, and especially TV news, to attain the “hot”-ness of information-dense media like print. As a medium, broadcast news is both “cool” and “medium cool”—and as such lukewarm.

The ideas coursing through Wexler's film may scan as academic, but they're grounded by the potency of its narrative. Like All the President's Men, Absence of Malice, and the whole broad canon of ennobled American journalist-themed cinema, Medium Cool follows Forster's John as he struggles to excavate the truth and humanity at the heart of the anti-war and black power movements. The structuring difference is that, as a camera operator, John is seen by higher-ups at his network as the broadcast equivalent of a typewriter: in place merely to record the news, not evaluate newsworthiness. When he finds out this his network has been handing his tapes over to Chicago's police, and the F.B.I., his outrage is so intense because he's realizing his diminished role as an adjunct to journalism, rather than a journalist, in place to help sell feeling and sensation rather than information and awareness.

Roger Ebert: Conventional movie plots telegraph themselves because we know all the basic genres and typical characters. Haskell Wexler's "Medium Cool" is one of several new movies that knows these things about the movie audience (others include "The Rain People," "Easy Rider," "Alice's Restaurant," etc.). Of the group, "Medium Cool" is probably the best. That may be because Wexler, for most of his career, has been a very good cinematographer, and so he's trained to see a movie in terms of its images, not its dialog and story.

In "Medium Cool," Wexler forges back and forth through several levels. There is a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his romance, his job, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a series of set-up situations that pretend to be real (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictional characters in real situations (the girl searching for her son in Grant Park). There are real characters in fictional situations (the real boy, playing a boy, expressing his real interest in pigeons).

The mistake would be to separate the real things from the fictional. They are all significant in exactly the same way. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the melodramatic accident that ends the film. All the images have meaning because of the way they are associated with each other.

And "Medium Cool" also does the second thing -- sees not the symbols but their function.

Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the life style, and he doesn't hear the words. He sees their function; they are there, entirely because the National Guard is there, and vice versa.

Both sides have a function only when they confront each other. Without the confrontation, all you'd have would be the kids, scattered all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week at their regular jobs. So it's not what they are that's important -- it's what they're doing there.

Wexler does the third thing, too. He evokes our memories of the hundreds of other movies we've seen to imply things about his story that he never explains on the screen.

The basic story of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, gradually wins friendship of her hostile son) is certainly not original. If Wexler had spelled it out, it would have been conventional and boring.

Instead, he limits himself to the characteristic and significant aspects of this relationship (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman seems more genuine to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The rest of the romance is implied but never shown; we skip B on our way from A to C.

"Medium Cool" is finally so important, and absorbing because of the way Wexler weaves all these elements together. He has made an almost perfect example of the new movie. Because we are so aware this is a movie, It seems more relevant and real than the smooth fictional surface of, say, "Midnight Cowboy."

This is even true of the last scene -- that accident that happens for no reason at all. Accidents are always accidents, and they always happen for no reason at all. When we get it, it occurs to us that it's the first movie accident we've ever seen that we weren't expecting for at least five minutes.

NYTimes: The movie, however, is much less complex than it looks. The story of the gradual emotional and political awakening of John Cassellis is somehow dwarfed by the emotional and political meaning of the events themselves, which we, in the audience, experience first hand, rather than through the movie protagonist. This is a fundamental problem in the kind of movie-making that attempts to homogenize fact and fiction, particularly when the fiction has the oversimplified shape of nineteen-thirties social protest drama and the fact is so obviously of a later, more complicated world.

Senses of Cinema: Admittedly, there are elements in Medium Cool that fall somewhat short. The kind of cinéma vérité filmmaking that was possible prior to the invention of the steadicam can test an audience’s equilibrium. Also, many of the shots in the film are composed more for the purpose of incorporating specific content than illustrating technical finesse. Wexler’s visual scheme succeeds more on the basis of its energy and audacity, and not its incorporation of memorable individual images. The flimsy plotline ties the individuals together much more than it explores, in-depth, their impulses and attitudes. Also, to some degree, the unlikelihood of the attraction between John and Ruth becomes sidetracked rather than grappled with, although the incorporation of working class characters remains one of the most compelling elements of the narrative.

Furthermore, the sexual politics now seem less acute and engaged than one might wish, although John’s exercise of his masculine prerogative mirrors most of the members of his gender at this point in time, if not currently. One wishes Wexler had the opportunity to explore more of the motivations that lie behind his seeming transformation once he encounters Ruth and Harold. The earlier sequences in the film that illustrate his seemingly altogether physical relationship with a nurse (Marianna Hill) convey the sense of someone with little sensitivity towards other people, let alone interest in the sexual independence of women.

The Guardian: Made with the advice and assistance of leading political activists (among them the legendary Chicago-based broadcaster and oral historian Studs Terkel), this was the first and by some way the best of Wexler’s only two films as a director. The other movie is the rarely seen Latino (1985), a passionate, partisan story (with a similar plot line to Medium Cool), in which a Hispanic special services officer serving with US special forces is assigned to train contra rebels to fight Sandinistas in Nicaragua and discovers he’s involved in a vicious secret war sponsored by the CIA to overthrow a legitimate leftwing government. Medium Cool encapsulates the divisive issues of race and poverty that remain as urgent today as they did in 1968. It also makes us think about the way the media shape our lives and are used to deflect public attention from sustained political action. In the film’s climax, the actors (Cassellis as photojournalist and his new girlfriend Eileen searching for her runaway son) become dangerously caught up in the real Chicago riots. The effect is unforgettable.

Art of the Title

The Making of 'Medium Cool': [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

Trailer

Vice: Haskell Wexler on 'Medium Cool'

Slant: Taking its name from the McLuhanist barometer of hot/cool media, Medium Cool analyzes the potential of television. “Medium cool” works as a pun, pointing at once to McLuhan's diagnosis of TV as a passive, “cool” medium, one that “requires a higher sensory involvement from the user,” as well as to the latent possibility for TV, and especially TV news, to attain the “hot”-ness of information-dense media like print. As a medium, broadcast news is both “cool” and “medium cool”—and as such lukewarm.

The ideas coursing through Wexler's film may scan as academic, but they're grounded by the potency of its narrative. Like All the President's Men, Absence of Malice, and the whole broad canon of ennobled American journalist-themed cinema, Medium Cool follows Forster's John as he struggles to excavate the truth and humanity at the heart of the anti-war and black power movements. The structuring difference is that, as a camera operator, John is seen by higher-ups at his network as the broadcast equivalent of a typewriter: in place merely to record the news, not evaluate newsworthiness. When he finds out this his network has been handing his tapes over to Chicago's police, and the F.B.I., his outrage is so intense because he's realizing his diminished role as an adjunct to journalism, rather than a journalist, in place to help sell feeling and sensation rather than information and awareness.

Roger Ebert: Conventional movie plots telegraph themselves because we know all the basic genres and typical characters. Haskell Wexler's "Medium Cool" is one of several new movies that knows these things about the movie audience (others include "The Rain People," "Easy Rider," "Alice's Restaurant," etc.). Of the group, "Medium Cool" is probably the best. That may be because Wexler, for most of his career, has been a very good cinematographer, and so he's trained to see a movie in terms of its images, not its dialog and story.

In "Medium Cool," Wexler forges back and forth through several levels. There is a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his romance, his job, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a series of set-up situations that pretend to be real (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictional characters in real situations (the girl searching for her son in Grant Park). There are real characters in fictional situations (the real boy, playing a boy, expressing his real interest in pigeons).

The mistake would be to separate the real things from the fictional. They are all significant in exactly the same way. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the melodramatic accident that ends the film. All the images have meaning because of the way they are associated with each other.

And "Medium Cool" also does the second thing -- sees not the symbols but their function.

Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the life style, and he doesn't hear the words. He sees their function; they are there, entirely because the National Guard is there, and vice versa.

Both sides have a function only when they confront each other. Without the confrontation, all you'd have would be the kids, scattered all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week at their regular jobs. So it's not what they are that's important -- it's what they're doing there.

Wexler does the third thing, too. He evokes our memories of the hundreds of other movies we've seen to imply things about his story that he never explains on the screen.

The basic story of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, gradually wins friendship of her hostile son) is certainly not original. If Wexler had spelled it out, it would have been conventional and boring.

Instead, he limits himself to the characteristic and significant aspects of this relationship (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman seems more genuine to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The rest of the romance is implied but never shown; we skip B on our way from A to C.

"Medium Cool" is finally so important, and absorbing because of the way Wexler weaves all these elements together. He has made an almost perfect example of the new movie. Because we are so aware this is a movie, It seems more relevant and real than the smooth fictional surface of, say, "Midnight Cowboy."

This is even true of the last scene -- that accident that happens for no reason at all. Accidents are always accidents, and they always happen for no reason at all. When we get it, it occurs to us that it's the first movie accident we've ever seen that we weren't expecting for at least five minutes.

NYTimes: The movie, however, is much less complex than it looks. The story of the gradual emotional and political awakening of John Cassellis is somehow dwarfed by the emotional and political meaning of the events themselves, which we, in the audience, experience first hand, rather than through the movie protagonist. This is a fundamental problem in the kind of movie-making that attempts to homogenize fact and fiction, particularly when the fiction has the oversimplified shape of nineteen-thirties social protest drama and the fact is so obviously of a later, more complicated world.

Senses of Cinema: Admittedly, there are elements in Medium Cool that fall somewhat short. The kind of cinéma vérité filmmaking that was possible prior to the invention of the steadicam can test an audience’s equilibrium. Also, many of the shots in the film are composed more for the purpose of incorporating specific content than illustrating technical finesse. Wexler’s visual scheme succeeds more on the basis of its energy and audacity, and not its incorporation of memorable individual images. The flimsy plotline ties the individuals together much more than it explores, in-depth, their impulses and attitudes. Also, to some degree, the unlikelihood of the attraction between John and Ruth becomes sidetracked rather than grappled with, although the incorporation of working class characters remains one of the most compelling elements of the narrative.

Furthermore, the sexual politics now seem less acute and engaged than one might wish, although John’s exercise of his masculine prerogative mirrors most of the members of his gender at this point in time, if not currently. One wishes Wexler had the opportunity to explore more of the motivations that lie behind his seeming transformation once he encounters Ruth and Harold. The earlier sequences in the film that illustrate his seemingly altogether physical relationship with a nurse (Marianna Hill) convey the sense of someone with little sensitivity towards other people, let alone interest in the sexual independence of women.

The Guardian: Made with the advice and assistance of leading political activists (among them the legendary Chicago-based broadcaster and oral historian Studs Terkel), this was the first and by some way the best of Wexler’s only two films as a director. The other movie is the rarely seen Latino (1985), a passionate, partisan story (with a similar plot line to Medium Cool), in which a Hispanic special services officer serving with US special forces is assigned to train contra rebels to fight Sandinistas in Nicaragua and discovers he’s involved in a vicious secret war sponsored by the CIA to overthrow a legitimate leftwing government. Medium Cool encapsulates the divisive issues of race and poverty that remain as urgent today as they did in 1968. It also makes us think about the way the media shape our lives and are used to deflect public attention from sustained political action. In the film’s climax, the actors (Cassellis as photojournalist and his new girlfriend Eileen searching for her runaway son) become dangerously caught up in the real Chicago riots. The effect is unforgettable.

Art of the Title

The Making of 'Medium Cool': [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

Trailer

Vice: Haskell Wexler on 'Medium Cool'

I just saw this in a local art house. Surprised at how much I didn't take to it. Maybe it's one of those films that suffers from being more innovative than good, so when the techniques get absorbed elsewhere they lose their potency. Also, hated the ending, it felt like the mandatory dose of shock-violence for a 1969 "serious" film.

I do respect how the director tried to turn his surprise footage of the riots into something compelling for his fictional film.

posted by praemunire at 2:01 PM on August 4

I do respect how the director tried to turn his surprise footage of the riots into something compelling for his fictional film.

posted by praemunire at 2:01 PM on August 4

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by octothorpe at 3:36 PM on May 29, 2016