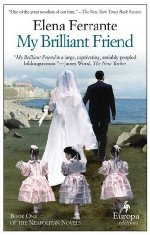

My Brilliant Friend

August 7, 2016 6:26 AM - by Elena Ferrante - Subscribe

A modern masterpiece from one of Italy’s most acclaimed authors, My Brilliant Friend is a rich, intense, and generous-hearted story about two friends, Elena and Lila. Ferrante’s inimitable style lends itself perfectly to a meticulous portrait of these two women that is also the story of a nation and a touching meditation on the nature of friendship. The story begins in the 1950s, in a poor but vibrant neighborhood on the outskirts of Naples. Growing up on these tough streets the two girls learn...

(Original title: L'amica geniale.) The book, indeed, the series, has been mentioned, over on the blue, a number of times, but it seems useful to have a thread here for the actual volumes. (Also: it would be brilliant and fitting if we could avoid any discussion of the author's identity.)

I'm reading them in Italian, so I'm happy to answer any questions regarding the original language. For instance: town of cats asked about Ferrante's use of dialect - interestingly, turns out there's virtually no direct use of dialect in tbe book (much unlike, for example, Camilleri), with the author usually just specifying when someone says something in dialect, or instead chooses to say it in Italian.

Actually, here's a question for readers of the English translation [MINOR SPOILER ALERT]: how is don Achille's black bag rendered?

(Original title: L'amica geniale.) The book, indeed, the series, has been mentioned, over on the blue, a number of times, but it seems useful to have a thread here for the actual volumes. (Also: it would be brilliant and fitting if we could avoid any discussion of the author's identity.)

I'm reading them in Italian, so I'm happy to answer any questions regarding the original language. For instance: town of cats asked about Ferrante's use of dialect - interestingly, turns out there's virtually no direct use of dialect in tbe book (much unlike, for example, Camilleri), with the author usually just specifying when someone says something in dialect, or instead chooses to say it in Italian.

Actually, here's a question for readers of the English translation [MINOR SPOILER ALERT]: how is don Achille's black bag rendered?

In that case, one thing that's lost in translation is that "borsa nera" means both "black bag", his terrifying attribute in the girls' eyes, but also "black market", which, we later learn, his wealth derives from. It adds a layer of the kind of thing that filters through, colouring their childhood.

posted by progosk at 10:04 AM on August 7, 2016 [7 favorites]

posted by progosk at 10:04 AM on August 7, 2016 [7 favorites]

I'm so surprised to hear that the characters aren't constantly switching into dialect that adds a ton of texture to the story! I mean, I guess I'm glad as I felt that was something I was really missing in translation.

I'm worried this thread won't get too big because many readers devoured these books all in one go and won't want to spoil later installments. I have no memory of what parts of the story happen in what volumes, they all blend together for me.

posted by town of cats at 1:27 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

I'm worried this thread won't get too big because many readers devoured these books all in one go and won't want to spoil later installments. I have no memory of what parts of the story happen in what volumes, they all blend together for me.

posted by town of cats at 1:27 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

Yeah, maybe when I reread it I will come back to this thread, but for now, trying to figure out what to say is like trying to say why I love my family, or some other truth so inherent in my life anything I could say about it would be a dumb platitude. I grew up in a situation that felt very familiar when I read this book, so it spoke to me very deeply.

posted by tofu_crouton at 1:48 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

posted by tofu_crouton at 1:48 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

Leaving dialect behind is a major thing for Elena, and so the fact that she doesn't resort to it as an exoticist embellishment is in line with both the narrative rigor that she's always striving towards, and part of her own need to pull free from the trappings of the rione.

posted by progosk at 1:50 PM on August 7, 2016 [3 favorites]

posted by progosk at 1:50 PM on August 7, 2016 [3 favorites]

I think she just says 'neighborhood'.

posted by tofu_crouton at 1:55 PM on August 7, 2016

posted by tofu_crouton at 1:55 PM on August 7, 2016

Yeah, part of why these books resonated so deeply for me is that I spent much of college trying to lose an embarrassing accent. I've tried to write fiction that used my teenage style of English before, and it never lands. I imagine Ferrante considered rendering the dialect bits in dialect and made the understandable choice not to.

And yes I think it's just the "neighborhood".

posted by town of cats at 1:58 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

And yes I think it's just the "neighborhood".

posted by town of cats at 1:58 PM on August 7, 2016 [1 favorite]

In answer to a direct question about her eschewing the use of the dialect, she said: «As a child and as a teenager, the dialect spoken in my city was scary to my ears. I prefer to have it echo among the Italian occasionally, as a kind of menace to the language."

posted by progosk at 3:03 PM on August 7, 2016 [3 favorites]

posted by progosk at 3:03 PM on August 7, 2016 [3 favorites]

I'm one of those people who devoured the books one after the other, so I don't totally remember what happened in which book specifically. But I remember very vividly the scene from the first book where Lila and Elena are on their way to the sea and Lila makes them turn back. Elena can't figure out if it is because Lila doesn't want Elena to get in trouble or for some other more selfish motive and that to me was so emblematic of their relationship and my relationship to Lila throughout the books - you can never really know for certain why she is doing certain things, or what her underlying motivations are. It was very powerful, to me, especially in the context of close, possible co-dependent female friendships.

posted by hepta at 4:10 PM on August 7, 2016 [5 favorites]

posted by hepta at 4:10 PM on August 7, 2016 [5 favorites]

I think my Italian is still far too rudimentary to try reading it in the original, but I want to. The translation seems pretty good though, in that it keeps what must be the original's strong descriptive voice. The stories of them as girls makes me remember so many thoughts and emotions from my own childhood , despite having very little in common with either.

posted by PussKillian at 7:48 PM on August 7, 2016

posted by PussKillian at 7:48 PM on August 7, 2016

The title drop of this novel is one of my favorite moments in literature -- like everything Lila does, it's heartfelt and full of pathos and also a deep, deep knife-twisting. Totally unexpected that instead of a plain reference to Lila, the title is Elena bitterly quoting Lila's description of her.

posted by thesmallmachine at 9:24 PM on August 7, 2016 [10 favorites]

posted by thesmallmachine at 9:24 PM on August 7, 2016 [10 favorites]

the title is Elena bitterly quoting Lila's description of her

Just went to look back at that bit [SPOLIER!, btw] and, yeah, it's an unexpected moment, which the narratrix plays on us readers on purpose, for sure - but I wouldn't say Elena's exactly bitter about her Lila's moniker for her, at least not at the moment she recounts it in the story: it's when Lila's first facing her fundamental doubt about the marriage, just as Elena's helping her get ready for the altar, and it's couched in one of those categoricals of Lila's about things. Studying should never end for you, she tells Elena, she wants her to be brilliant beyond all the others, beyond all the "maschi e femmine". (And it's a moment followed by the most intimate moment of theirs, as Lenù washes her.)

Of course, there are moments in which Elena will be deeply ironic/sarcastic/self-doubting about this descriptor as applied to herself, but on the whole, it seems to encapsulate something benevolent of their singular mirroring interplay, the recognition that only the force of will, intellect and friendship/connection can be their chance to stake out their destinies.

posted by progosk at 3:03 AM on August 8, 2016 [3 favorites]

Just went to look back at that bit [SPOLIER!, btw] and, yeah, it's an unexpected moment, which the narratrix plays on us readers on purpose, for sure - but I wouldn't say Elena's exactly bitter about her Lila's moniker for her, at least not at the moment she recounts it in the story: it's when Lila's first facing her fundamental doubt about the marriage, just as Elena's helping her get ready for the altar, and it's couched in one of those categoricals of Lila's about things. Studying should never end for you, she tells Elena, she wants her to be brilliant beyond all the others, beyond all the "maschi e femmine". (And it's a moment followed by the most intimate moment of theirs, as Lenù washes her.)

Of course, there are moments in which Elena will be deeply ironic/sarcastic/self-doubting about this descriptor as applied to herself, but on the whole, it seems to encapsulate something benevolent of their singular mirroring interplay, the recognition that only the force of will, intellect and friendship/connection can be their chance to stake out their destinies.

posted by progosk at 3:03 AM on August 8, 2016 [3 favorites]

It's pretty much a perfect book - each sentence is so thoughtfully crafted, each fitting in it's niche. It reminded me of The God of Small Things or Beloved in that way. Like, no word is by accident in this book. I adored it.

Count me among the surprised that there is no dialect in the Italian.

I think someone on metafilter suggested that there should be a film version but it should be shot in a contemporary setting. Housing project in the South Side of Chicago or something. I think that would be brilliant.

It's rare that I love a book so much that isn't somehow really weird - I generally feel passionate about books that are doing something unsettling with the form - and this book is very straightforward. But it's so perfect. It's like having a perfectly crafted loaf of bread from the best local bakery or something.

For reasons that are not clear to me, I'm not especially interested in reading the rest of the series.

posted by latkes at 7:57 AM on August 9, 2016

Count me among the surprised that there is no dialect in the Italian.

I think someone on metafilter suggested that there should be a film version but it should be shot in a contemporary setting. Housing project in the South Side of Chicago or something. I think that would be brilliant.

It's rare that I love a book so much that isn't somehow really weird - I generally feel passionate about books that are doing something unsettling with the form - and this book is very straightforward. But it's so perfect. It's like having a perfectly crafted loaf of bread from the best local bakery or something.

For reasons that are not clear to me, I'm not especially interested in reading the rest of the series.

posted by latkes at 7:57 AM on August 9, 2016

For reasons that are not clear to me, I'm not especially interested in reading the rest of the series.

I can understand that sentiment. This particular volume is, as you said, perfectly crafted. It seems like it doesn't need an extension. It's an egg, containing all it needs within it.

And some of the later volumes are frustrating. I think they're worth it though.

posted by tofu_crouton at 8:18 AM on August 9, 2016 [1 favorite]

I can understand that sentiment. This particular volume is, as you said, perfectly crafted. It seems like it doesn't need an extension. It's an egg, containing all it needs within it.

And some of the later volumes are frustrating. I think they're worth it though.

posted by tofu_crouton at 8:18 AM on August 9, 2016 [1 favorite]

I found it a bit hard to get into at the beginning, but I'm glad I stuck with it. I loved this book so much and I've recommended it to my mom and grandma, among others. When I got to the end, I needed to get the second book to find out what happened next. (Hooray for it being available via Overdrive and my local library.)

posted by SisterHavana at 11:55 PM on August 9, 2016

posted by SisterHavana at 11:55 PM on August 9, 2016

Lenu develops a facility with Italian to raise herself above her childhood dialect, away from the harshness and vulgarity she sees around her; it makes perfect sense to me that there should be so little of it in the Italian version. I think of Lenu's language acquisition as another container, a sort of vessel for her invented self, an additional grammar of being, with clear rules--a containing vessel that's insufficient to contain Lina, whether Italian or Latin or Greek. She keeps pushing against things to find out their limits, and her own (I am thinking particularly of her treatment of the teacher, and of that teacher's devastating, if much-delayed, delimitation of Cerullo). Her actions are so often oriented toward establishing who can stop her, who or what is powerful enough to do so. If not Don Achille or the basement, when who or what? I think that when Lina and Lenu walk to the sea, Lina is afraid of Lenu's absence of fear of going into what is not known--in fact, her excitement at the prospect. It is a far cry from Lina's "I dare you" framework, and a moment of very deep individuation between the two of them. Similarly, Lina's wedding night, with parallel experiences, one within an established framework and one outside of it. Form is not freedom from fear, though, is it? And lack of form--of approved vessels of being--is not freedom, but a tightrope, thin, high, without a net. [All this written after reading these four novels, and The Days of Abandonment as well, which is deeply concerned with what happens to the self when a familiar maker/container of self is unexpectedly obliterated.]

Thank you for posting this, progosk. I'm looking forward to the discussion!

posted by MonkeyToes at 12:33 PM on August 11, 2016 [3 favorites]

Thank you for posting this, progosk. I'm looking forward to the discussion!

posted by MonkeyToes at 12:33 PM on August 11, 2016 [3 favorites]

Also, is this the place where we can discuss the vast multitudes of emotion that inhabit Lina and Lenu's friendship? It feels tidal to me, and dynamic, and interdependent, and unlike so many other depictions of female friendship that I've read over the years. I was...unprepared for how raw (aggressiion-filled? competitive? viscerally necessary?) it is.

heartfelt and full of pathos and also a deep, deep knife-twisting

Yes!

posted by MonkeyToes at 2:26 PM on August 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

heartfelt and full of pathos and also a deep, deep knife-twisting

Yes!

posted by MonkeyToes at 2:26 PM on August 11, 2016 [1 favorite]

(I was of two minds whether a collective, four-volume Neapotlitan Novels post would have been more apt, but it seemed arbitrarily post-hoc. I'm just nearing the end of the second volume, so unless someone else does so before me, I'll get around to making posts for the other three volumes soon - I'm finding myself just drinking these texts in, in deep, unpausing draughts.)

posted by progosk at 3:08 PM on August 11, 2016

posted by progosk at 3:08 PM on August 11, 2016

Form is not freedom from fear, though, is it? And lack of form--of approved vessels of being--is not freedom, but a tightrope, thin, high, without a net.

The issue of form, of how the self is framed, felt really crucial throughout. Elena's painstaking attempt to describe Lila's terrified instances of "smarginatura", when others lose their contours, their primal animus oozing out, and things burst apart - like some of the more frightening Miyazaki waking nightmare moments - are an extreme case in point. (What's smarginatura in the English?)

I loved this book so much and I've recommended it to my mom and grandma, among others.

Given the book's portrayal of mothers and family heredity in general, is that kind of a fraught recommendation to make?

posted by progosk at 11:55 PM on August 11, 2016

The issue of form, of how the self is framed, felt really crucial throughout. Elena's painstaking attempt to describe Lila's terrified instances of "smarginatura", when others lose their contours, their primal animus oozing out, and things burst apart - like some of the more frightening Miyazaki waking nightmare moments - are an extreme case in point. (What's smarginatura in the English?)

I loved this book so much and I've recommended it to my mom and grandma, among others.

Given the book's portrayal of mothers and family heredity in general, is that kind of a fraught recommendation to make?

posted by progosk at 11:55 PM on August 11, 2016

Also, is this the place where we can discuss the vast multitudes of emotion that inhabit Lina and Lenu's friendship? It feels tidal to me, and dynamic, and interdependent, and unlike so many other depictions of female friendship that I've read over the years. I was...unprepared for how raw (aggressiion-filled? competitive? viscerally necessary?) it is.

In an email interview, Ferrante notes: "Male friendship can count on a longstanding literary tradition and a well-defined code of behaviours. For female friendship there is at best an approximate map, which is only recently taking clearer shape. There's a risk that the shortcuts of commonplace win out over the effort to take more arduous routes." (My translation; interestingly, the original interview is in Spanish; in Italian it was published shortened, and translated.)

posted by progosk at 3:04 AM on August 12, 2016

In an email interview, Ferrante notes: "Male friendship can count on a longstanding literary tradition and a well-defined code of behaviours. For female friendship there is at best an approximate map, which is only recently taking clearer shape. There's a risk that the shortcuts of commonplace win out over the effort to take more arduous routes." (My translation; interestingly, the original interview is in Spanish; in Italian it was published shortened, and translated.)

posted by progosk at 3:04 AM on August 12, 2016

"[Lina] was alone in the kitchen washing the dishes and was tired, really without energy, when there was an explosion. She had turned suddenly and realized that the big copper pot had exploded. Like that, by itself. It was hanging on the nail where it normally hung, but in the middle there was a large hole and the rim was lifted and twisted and the pot itself was all deformed, as if it could no longer maintain its appearance as a pot."

I admire this passage for its domestic terror, and the way it conveys anxiety over the loss of form, over unexplained deformation. It's one of the few things Lila can't make up a story for. A story for murder? Yes. For the black marketeer, yes. But not this pot. And she very plainly sees it as a terrifying omen and admits to being afraid. Although I agree with the earlier comment about Lina's deep knife-twisting, I also see this as one of Lina's few moments of candor and vulnerability, even if she has re-written it many times to get it right. (Who else in her world at that point would understand? But as much as it's a vote of confidence in Lenu's ability to recognize ambiguities, it's also a burden and a plea for order. And everything, everything in their relationship is suspended within that vital need for the other to be, or maybe to guarantee the other's existence. How far can that dynamic be pushed before breaking?) I appreciate the idea of these novels as an investigation of female friendship and its capacious and porous boundaries, and one that has nothing at all to do with most other depictions. The dolls--God, the dolls--and the cellar "where the darkness might suddenly seize the dolls." Was Lina testing whether Lenu would allow her, or herself, to be devoured by a man in the dark, by the black bag? Again, who else would have gone into that cellar? Who else in the neighborhood would be both an equal peer and someone strong enough to provide a sense of safety? Every knife-twist is a test. My God, what is this friendship? A thing strong enough, maybe, to restore the copper pot and all of the other shapeless anxieties of their lives to meaning.

posted by MonkeyToes at 5:49 PM on August 12, 2016 [1 favorite]

I admire this passage for its domestic terror, and the way it conveys anxiety over the loss of form, over unexplained deformation. It's one of the few things Lila can't make up a story for. A story for murder? Yes. For the black marketeer, yes. But not this pot. And she very plainly sees it as a terrifying omen and admits to being afraid. Although I agree with the earlier comment about Lina's deep knife-twisting, I also see this as one of Lina's few moments of candor and vulnerability, even if she has re-written it many times to get it right. (Who else in her world at that point would understand? But as much as it's a vote of confidence in Lenu's ability to recognize ambiguities, it's also a burden and a plea for order. And everything, everything in their relationship is suspended within that vital need for the other to be, or maybe to guarantee the other's existence. How far can that dynamic be pushed before breaking?) I appreciate the idea of these novels as an investigation of female friendship and its capacious and porous boundaries, and one that has nothing at all to do with most other depictions. The dolls--God, the dolls--and the cellar "where the darkness might suddenly seize the dolls." Was Lina testing whether Lenu would allow her, or herself, to be devoured by a man in the dark, by the black bag? Again, who else would have gone into that cellar? Who else in the neighborhood would be both an equal peer and someone strong enough to provide a sense of safety? Every knife-twist is a test. My God, what is this friendship? A thing strong enough, maybe, to restore the copper pot and all of the other shapeless anxieties of their lives to meaning.

posted by MonkeyToes at 5:49 PM on August 12, 2016 [1 favorite]

What a powerful book and series; I'm on the third book now, and am looking forward to the discussions of all four. I like the translation in general, but as I wrote in this LH post about the second volume (post includes spoiler, if you haven't read that volume):

My wife (who's already finished the series—we've passed the second volume on to our daughter-in-law and the first to my sister-in-law) has a question perhaps progosk can answer: what are the connotations of the various forms of the names (Elena/Lenù/Lenuccia, etc.)? And what does it mean that some characters (e.g., Stefano) are only ever referred to by one form?

(Thanks to MonkeyToes for alerting me to this thread!)

posted by languagehat at 11:19 AM on August 15, 2016 [2 favorites]

I have to say, by the way, that while Ann Goldstein, the translator, seems to do a good job, she has a tic that annoys me: she can’t seem to resist translating invece as “instead.” Obviously she knows as well as I do that it’s used more widely than the English word and that sometimes it’s better to use “but” or “on the other hand” or just not translate it, but habit gets the better of us all.(I was checking the Italian via Google Books; alas, they appear not to have digitized the books after the second volume.)

My wife (who's already finished the series—we've passed the second volume on to our daughter-in-law and the first to my sister-in-law) has a question perhaps progosk can answer: what are the connotations of the various forms of the names (Elena/Lenù/Lenuccia, etc.)? And what does it mean that some characters (e.g., Stefano) are only ever referred to by one form?

(Thanks to MonkeyToes for alerting me to this thread!)

posted by languagehat at 11:19 AM on August 15, 2016 [2 favorites]

Hmm, I see by checking the tags there's already a post for the second volume; there are no comments yet, so maybe nobody's noticed it, so I thought I'd link to it here.

posted by languagehat at 11:22 AM on August 15, 2016

posted by languagehat at 11:22 AM on August 15, 2016

(Disclaimer: though my acquired family's from a city just an hour south of Naples - and so of course claim a very distinct dialect from the capoluogo - my knowledge of Neapolitan isn't exactly first-hand.)

Personal nomenclature is one of the many things Ferrante's quite careful about. As the story progresses, each character picks up a collection of names, and each is used quite specifically, mostly related to who's speaking, their emotional intent, and in which social context. Regarding Elena's, the diminutive suffix -uccia is a common Southern appendix used to compose a name's vezzeggiativo; up North it might more typically be -ina (Tuscany) or -etta (Rome). So Elenuccia, economised to Lenuccia is simply the affectionate, familiar way to call her. The even more intimate shortening to Lenù (interestingly: in the Spanish translation the accent is flipped; have they kept it in the English? I often see people refer to her as Lenu, sans accent at all) is more of a nickname, for her closest circle of friends, usually for intimate moments. My wife's first name has exactly the same two declinations, so it's pretty par for the regional course, as far as I can tell.

(Fun fact: Roman intimate nickname shortening will usually entail an even more radical dropping of sillables, to all but one, so if theses novels had been set somewhere like the Quadraro, or Tor Bella Monaca, the two heroines would likely be reduced to Lé and Lì, or perhaps Rà.)

Of course her best friend is twice the exception: Raffaelluccia is too clunky, so it gets -ina, and with the same front-end foreshortening she's Lina. But Elena has a personal nickname for her, which she jealously keeps for her own exclusive us: Lila - which, like Lenù, preserves something of the approximation/simplification so typical of childhood names for one another.

Were you suspecting more/other connotations than these (fairly normal naming conventions)?

As regards Stefano: he actually does become just "Carracci" at a certain point, but I don't want to pre-empt anything here. (I'm just starting on the fourth, so the post for book three will go up soon.)

posted by progosk at 2:07 PM on August 15, 2016 [4 favorites]

Personal nomenclature is one of the many things Ferrante's quite careful about. As the story progresses, each character picks up a collection of names, and each is used quite specifically, mostly related to who's speaking, their emotional intent, and in which social context. Regarding Elena's, the diminutive suffix -uccia is a common Southern appendix used to compose a name's vezzeggiativo; up North it might more typically be -ina (Tuscany) or -etta (Rome). So Elenuccia, economised to Lenuccia is simply the affectionate, familiar way to call her. The even more intimate shortening to Lenù (interestingly: in the Spanish translation the accent is flipped; have they kept it in the English? I often see people refer to her as Lenu, sans accent at all) is more of a nickname, for her closest circle of friends, usually for intimate moments. My wife's first name has exactly the same two declinations, so it's pretty par for the regional course, as far as I can tell.

(Fun fact: Roman intimate nickname shortening will usually entail an even more radical dropping of sillables, to all but one, so if theses novels had been set somewhere like the Quadraro, or Tor Bella Monaca, the two heroines would likely be reduced to Lé and Lì, or perhaps Rà.)

Of course her best friend is twice the exception: Raffaelluccia is too clunky, so it gets -ina, and with the same front-end foreshortening she's Lina. But Elena has a personal nickname for her, which she jealously keeps for her own exclusive us: Lila - which, like Lenù, preserves something of the approximation/simplification so typical of childhood names for one another.

Were you suspecting more/other connotations than these (fairly normal naming conventions)?

As regards Stefano: he actually does become just "Carracci" at a certain point, but I don't want to pre-empt anything here. (I'm just starting on the fourth, so the post for book three will go up soon.)

posted by progosk at 2:07 PM on August 15, 2016 [4 favorites]

Thanks!

> Were you suspecting more/other connotations than these (fairly normal naming conventions)?

No, that's what I would have guessed, but I'd rather know than guess. I still don't get why some names get nicknames and others don't; it's not a male/female thing, because there's Gennaro/Rino/Rinuccio. But maybe Stefano just isn't a nicknameable guy.

> have they kept it in the English

Yup, it's Lenù. (From the perspective of a Spanish-speaker, it's Italian which has done a weird accent-flipping thing!)

posted by languagehat at 2:53 PM on August 15, 2016

> Were you suspecting more/other connotations than these (fairly normal naming conventions)?

No, that's what I would have guessed, but I'd rather know than guess. I still don't get why some names get nicknames and others don't; it's not a male/female thing, because there's Gennaro/Rino/Rinuccio. But maybe Stefano just isn't a nicknameable guy.

> have they kept it in the English

Yup, it's Lenù. (From the perspective of a Spanish-speaker, it's Italian which has done a weird accent-flipping thing!)

posted by languagehat at 2:53 PM on August 15, 2016

> I'm just starting on the fourth, so the post for book three will go up soon.

By the way, I was horrified when I went to the main page of Fanfare to see your post beginning "In book three...." Couldn't you just put "Book three" and the title above the fold, and the plot description underneath, so only those who have read the book (or don't care about spoilers) will see it? Fortunately I was able to back out without seeing any details, but I shudder to think what might have happened!

posted by languagehat at 3:02 PM on August 15, 2016

By the way, I was horrified when I went to the main page of Fanfare to see your post beginning "In book three...." Couldn't you just put "Book three" and the title above the fold, and the plot description underneath, so only those who have read the book (or don't care about spoilers) will see it? Fortunately I was able to back out without seeing any details, but I shudder to think what might have happened!

posted by languagehat at 3:02 PM on August 15, 2016

Oh, and I remembered another question I wanted to ask: would someone familiar with Naples know where her neighborhood was, or is it deliberately kept too vague to identify (which I suppose is more likely the case)?

posted by languagehat at 3:05 PM on August 15, 2016

posted by languagehat at 3:05 PM on August 15, 2016

By the way, I was horrified when I went to the main page of Fanfare to see your post beginning "In book three...." Couldn't you just put "Book three" and the title above the fold, and the plot description underneath, so only those who have read the book (or don't care about spoilers) will see it? Fortunately I was able to back out without seeing any details, but I shudder to think what might have happened!

True, actually - it's a FanFare Books feature, that fishes the summary blurb (from Amazon?), once you do the book verification thing; I actually fleshed the blurb out a bit, too... could a mod move the details below the fold, please?

posted by progosk at 3:55 PM on August 15, 2016

True, actually - it's a FanFare Books feature, that fishes the summary blurb (from Amazon?), once you do the book verification thing; I actually fleshed the blurb out a bit, too... could a mod move the details below the fold, please?

posted by progosk at 3:55 PM on August 15, 2016

would someone familiar with Naples know where her neighborhood was, or is it deliberately kept too vague to identify

The geography is actually pretty intricately described, the tunnels, the stagni, the rail tracks - I'll could have a look to see if anyone's attempted to pinpoint the rione. (Though I'm almost as hesitant to do that as I'm loath to play the doxx-the-author game a lot of the media was so eager about.)

Just to ask again: how is "smarginatura" translated?

posted by progosk at 4:01 PM on August 15, 2016

The geography is actually pretty intricately described, the tunnels, the stagni, the rail tracks - I'll could have a look to see if anyone's attempted to pinpoint the rione. (Though I'm almost as hesitant to do that as I'm loath to play the doxx-the-author game a lot of the media was so eager about.)

Just to ask again: how is "smarginatura" translated?

posted by progosk at 4:01 PM on August 15, 2016

could a mod move the details below the fold, please?

Wait - actually that's what the Hide Post Description option in FanFare is for right?

posted by progosk at 4:07 PM on August 15, 2016

Wait - actually that's what the Hide Post Description option in FanFare is for right?

posted by progosk at 4:07 PM on August 15, 2016

> The geography is actually pretty intricately described, the tunnels, the stagni, the rail tracks - I'll could have a look to see if anyone's attempted to pinpoint the rione.

I'd love to know, if you don't mind checking. (I really don't see that it's even in the same ballpark with who's-the-author, but if it bothers you, don't go down that rione.)

posted by languagehat at 5:15 PM on August 15, 2016

I'd love to know, if you don't mind checking. (I really don't see that it's even in the same ballpark with who's-the-author, but if it bothers you, don't go down that rione.)

posted by languagehat at 5:15 PM on August 15, 2016

It's the rione Luzzatti, part of the quartiere Gianturco, east of the city, apparently (via Smarginatura).

I half preferred the invention to be all-encompassing, including the place - if only to counter the "it's just autobiographical" faction more resoundingly.

posted by progosk at 5:43 AM on August 16, 2016

I half preferred the invention to be all-encompassing, including the place - if only to counter the "it's just autobiographical" faction more resoundingly.

posted by progosk at 5:43 AM on August 16, 2016

Thanks very much! I'm totally on board with countering the "it's just autobiographical" idiots, but I'm also obsessive about geography and have been following everything on maps of Naples (and god bless Google Maps and the internet in general for helping locate all sorts of obscure references!). For me, having a sense of where things are (and whatever historical/cultural associations are involved) is very important (and one reason I prefer books set in real places rather than "the provincial town of N"). And I'm pleased to learn that the quartiere Gianturco is more or less where I'd decided the rione must be, east of downtown and not too far from the water.

posted by languagehat at 7:10 AM on August 16, 2016

posted by languagehat at 7:10 AM on August 16, 2016

This link (in English) discussion the geography of the novel, as well as the housing and schooling of the neighborhood.

posted by Falconetti at 8:57 AM on August 16, 2016 [2 favorites]

posted by Falconetti at 8:57 AM on August 16, 2016 [2 favorites]

Wow, thanks for that great link. (Minor spoiler for the fourth book, so I won't send it around just yet.)

posted by languagehat at 9:11 AM on August 16, 2016

posted by languagehat at 9:11 AM on August 16, 2016

Just to ask again: how is "smarginatura" translated?

Maybe a couple years too late, but... in English this is what Lila calls "dissolving margins".

I just finished the set, and I'm curious to learn that even in the original Italian there is very little Neapolitan, but the same "so-and-so responded in dialect" found in the English. I wondered, is the reason Ferrante doesn't use actual Neapolitan dialog in the books because it would mean a large percentage of Italians would not be able to understand it? I know we call it a dialect, but as far as I can tell, it's not a dialect at all, but a parallel Italic language with not much mutual intelligibility with Italian. It would be as if an English novel had characters who would resort to speaking in Scots at various points in the story... an interesting literary device, but it would definitely shift the focus away from the relationships of the characters, and also alienate a big swath of potential readers who couldn't even get the gist of what they were saying.

posted by lefty lucky cat at 11:16 PM on February 7, 2019

Maybe a couple years too late, but... in English this is what Lila calls "dissolving margins".

I just finished the set, and I'm curious to learn that even in the original Italian there is very little Neapolitan, but the same "so-and-so responded in dialect" found in the English. I wondered, is the reason Ferrante doesn't use actual Neapolitan dialog in the books because it would mean a large percentage of Italians would not be able to understand it? I know we call it a dialect, but as far as I can tell, it's not a dialect at all, but a parallel Italic language with not much mutual intelligibility with Italian. It would be as if an English novel had characters who would resort to speaking in Scots at various points in the story... an interesting literary device, but it would definitely shift the focus away from the relationships of the characters, and also alienate a big swath of potential readers who couldn't even get the gist of what they were saying.

posted by lefty lucky cat at 11:16 PM on February 7, 2019

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by tofu_crouton at 8:24 AM on August 7, 2016