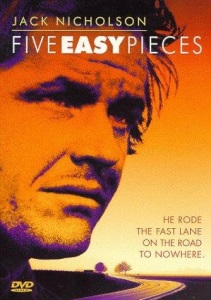

Five Easy Pieces (1970)

June 14, 2017 6:29 AM - Subscribe

Jack Nicholson (in the role that earned him a reputation as a serious actor, and an Academy Award nomination) portrays Bobby Dupea, a disaffected oil rig worker who goes on an existential journey back to his privileged roots.

Roger Ebert listed Five Easy Pieces as one of his "Great Movies." From the article:

"It is difficult to explain today how much Bobby Dupea meant to the film's first audiences. I was at the New York Film Festival for the premiere of Five Easy Pieces, and I remember the explosive laughter, the deep silences, the stunned attention as the final shot seemed to continue forever, and then the ovation. We'd had a revelation. This was the direction American movies should take: Into idiosyncratic characters, into dialogue with an ear for the vulgar and the literate, into a plot free to surprise us about the characters, into an existential ending not required to be happy. Five Easy Pieces was a fusion of the personal cinema of John Cassavetes and the new indie movement that was tentatively emerging. It was, you could say, the first Sundance film.

"[...] The last long scene, at the gas station, is the kind of ending the film deserves. It would not be allowed today, when happy endings are legislated by contract. It is true to the Bobby Dupea we have come to know. [...] Five Easy Pieces has the complexity, the nuance, the depth, of the best fiction. In involves us in these people, this time and place, and we care for them, even though they don't request our affection or applause."

Ebert's original 1970 review

Rotten Tomatoes score: 87%

(Previously proposed on FanFare Talk)

Roger Ebert listed Five Easy Pieces as one of his "Great Movies." From the article:

"It is difficult to explain today how much Bobby Dupea meant to the film's first audiences. I was at the New York Film Festival for the premiere of Five Easy Pieces, and I remember the explosive laughter, the deep silences, the stunned attention as the final shot seemed to continue forever, and then the ovation. We'd had a revelation. This was the direction American movies should take: Into idiosyncratic characters, into dialogue with an ear for the vulgar and the literate, into a plot free to surprise us about the characters, into an existential ending not required to be happy. Five Easy Pieces was a fusion of the personal cinema of John Cassavetes and the new indie movement that was tentatively emerging. It was, you could say, the first Sundance film.

"[...] The last long scene, at the gas station, is the kind of ending the film deserves. It would not be allowed today, when happy endings are legislated by contract. It is true to the Bobby Dupea we have come to know. [...] Five Easy Pieces has the complexity, the nuance, the depth, of the best fiction. In involves us in these people, this time and place, and we care for them, even though they don't request our affection or applause."

Ebert's original 1970 review

Rotten Tomatoes score: 87%

(Previously proposed on FanFare Talk)

I saw this relatively recently (in the last five years or so) and was left completely devastated by Nicholson's performance. This scene, in particular.

Though I've always enjoyed Nicholson's performances, I admittedly thought his reputation as one of our Great Actors was kind of mysterious, as I felt that the "Jack Nicholson" character was pretty clearly defined as early as Chinatown and Cuckoo's Nest. Five Easy Pieces was the movie where I finally said "Oh, I get it now."

posted by incomple at 8:30 AM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

Though I've always enjoyed Nicholson's performances, I admittedly thought his reputation as one of our Great Actors was kind of mysterious, as I felt that the "Jack Nicholson" character was pretty clearly defined as early as Chinatown and Cuckoo's Nest. Five Easy Pieces was the movie where I finally said "Oh, I get it now."

posted by incomple at 8:30 AM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

I haven't seen this or Puzzle of a Downfall Child in many years, but at the time both were relatively fresh I actually leaned towards Downfall Child as the one I preferred. But that was, in part, due to my inability to find much connection to Nicholson in Five Easy Pieces, something which keeps me from having much to say about the film since that early impression really isn't an adequate base to work from. I'm also quite fond of The Model Shop, which Eastwood wrote the English dialogue for, and The Shooting, but had mixed feelings on The Fortune, still, I'd agree a revisit of her short career may be in order.

Rafaelson did have a fair bit of trouble finding consistent work as well, which is also a real shame since he's a hell of a director when he's given the chance to work. Stay Hungry's a fine little film, and King of Marvin Gardens is a knockout. It's due to my seeing that again recently that makes me suspect I might find Five Easy Pieces a much better experience if/when I see it again. I'll try to keep it in mind when I go out to get movies again this weekend and see how it goes. Maybe I'll see if Man Trouble is still around too, I don't even remember if I've seen that before or not, but now that it's come up I kinda want to.

posted by gusottertrout at 12:26 PM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

Rafaelson did have a fair bit of trouble finding consistent work as well, which is also a real shame since he's a hell of a director when he's given the chance to work. Stay Hungry's a fine little film, and King of Marvin Gardens is a knockout. It's due to my seeing that again recently that makes me suspect I might find Five Easy Pieces a much better experience if/when I see it again. I'll try to keep it in mind when I go out to get movies again this weekend and see how it goes. Maybe I'll see if Man Trouble is still around too, I don't even remember if I've seen that before or not, but now that it's come up I kinda want to.

posted by gusottertrout at 12:26 PM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

When I did my first university degree, I said afterwards that there were three courses I took over the four years that would stick with me (I only remember two at this point, which perhaps says something). One of them was a course called The Psychology of Creativity, in which we examined creativity from a variety of psychological and philosophical schools of thought. It was thought provoking and engaging. It had a lab requirement, which was getting together as a group once every two weeks to watch a movie selected by the prof for the insights it had into creativity or the creative process. I was introduced to a great deal of interesting cinema that way, including Five Easy Pieces.

I remember the prof being enamored of the scene in the diner, where Bobby wants a side order of toast but has to order it by ordering the chicken salad sandwich on toast, hold everything but the bread ("you want me to hold the chicken?"/"I want you to hold it between your knees."). Nicholson at his sneering best, I guess. But for me it was the scene where he hops out of the car and starts playing the piano on the truck in the middle of a traffic jam. Something about it just works for me; I think it's the fact that it's not a deliberate thing, but more of a madcap, spur of the moment thing the character does. I think part of it was that my understanding of Jack the actor at that point was having seen him in roles long after he'd been established as a certain type, a certain role. But in Five Easy Pieces, he wasn't Jack just yet and I got to see someone who might just do something unexpected and different. I guess that scene just kind of encapsulates how I felt about the movie - it was unexpected and not how I thought of Jack Nicholson, and allowed me to see the character of Bobby as opposed to seeing Jack playing at being Bobby.

Anyways, a great film: tremendous script, great performances, and one that I think probably doesn't get enough attention.

posted by nubs at 1:26 PM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

I remember the prof being enamored of the scene in the diner, where Bobby wants a side order of toast but has to order it by ordering the chicken salad sandwich on toast, hold everything but the bread ("you want me to hold the chicken?"/"I want you to hold it between your knees."). Nicholson at his sneering best, I guess. But for me it was the scene where he hops out of the car and starts playing the piano on the truck in the middle of a traffic jam. Something about it just works for me; I think it's the fact that it's not a deliberate thing, but more of a madcap, spur of the moment thing the character does. I think part of it was that my understanding of Jack the actor at that point was having seen him in roles long after he'd been established as a certain type, a certain role. But in Five Easy Pieces, he wasn't Jack just yet and I got to see someone who might just do something unexpected and different. I guess that scene just kind of encapsulates how I felt about the movie - it was unexpected and not how I thought of Jack Nicholson, and allowed me to see the character of Bobby as opposed to seeing Jack playing at being Bobby.

Anyways, a great film: tremendous script, great performances, and one that I think probably doesn't get enough attention.

posted by nubs at 1:26 PM on June 14, 2017 [1 favorite]

Up through the piano scene, I was under the strong impression that Bobby and most of the other characters were under the influence of some substance or other basically all the time.

I just saw it for the first time (which inspired this post), and I'm definitely glad I did; it's nice to see Jack pre-self-caricature. As an early indie, you can absolutely feel its influence on other more "INDIE" indies. I mean that as sort of a partial compliment: it's got that slow burn, that great downbeat ending, that often oblique yet clearly meaningful dialogue—but it's also got that weird tangent with the hitchhikers. I guess maybe it connects somehow to the theme of class? But why does she talk so much? Is it meant to be funny?

posted by CheesesOfBrazil at 5:12 AM on June 15, 2017

I just saw it for the first time (which inspired this post), and I'm definitely glad I did; it's nice to see Jack pre-self-caricature. As an early indie, you can absolutely feel its influence on other more "INDIE" indies. I mean that as sort of a partial compliment: it's got that slow burn, that great downbeat ending, that often oblique yet clearly meaningful dialogue—but it's also got that weird tangent with the hitchhikers. I guess maybe it connects somehow to the theme of class? But why does she talk so much? Is it meant to be funny?

posted by CheesesOfBrazil at 5:12 AM on June 15, 2017

I have to watch it again before I say more, but I love this movie and none of it has to do with the diner scene.

posted by rhizome at 7:04 PM on June 17, 2017

posted by rhizome at 7:04 PM on June 17, 2017

Ah, yeah, after a rewatch, I see what the problem was in my first viewing. I evidently tuned out at the cringe inducing dinner party held after Rayette shows up at the family estate, and didn't take in the scenes following it very well. It's such a tight design that the film really doesn't gel until Bobby goes looking for Catherine and finds Tita in Spicer's room. Up to that point, it's of course suggestive, but elusive in suggesting an overall effect, well, gestalt really, but that's one of them fancy terms that might be better suited for a dinner party.

Without that, the movie evokes all too clearly a sense of Bobby's perspective, a feeling of unmatched demands and wants, from himself outwards and from others towards him. The relentlessness of those perceived demands on his own vaguely articulated, and likely vaguely understood, set of values makes the movie oppressive, requiring some sense of at least momentary relief to assess where the weight of the problem is coming from. My initial feeling was that the movie was too aligned with Bobby and didn't allow for enough space to see the other characters outside his perspective, which created some unwelcome feeling of his perspective being validated, inhibiting deeper assessment by way of caricature. That left the ending of the film at the gas station feeling a bit off as the tonal shift didn't feel entirely congruent with what came before.

On rewatch, I've modified my thinking a bit as I found the film much more successful than on my first viewing, but still with some lingering dissatisfaction over the dominating perspective of the film and its seeming effect on how one sees Bobby and the other characters.

It's now easier to appreciate the more necessary elements of the effect of adopting Bobby's perspective as the dominant tone for the movie, with it providing a meaningful tension to almost every scene, starting from Bobby first entering the house he shares with Rayette, up until the conversation with Samia at his childhood home, with only the momentary diversion of his piano playing on the back of the truck providing the distance to see Bobby rather than be caught up in his emotional state. That latter scene being matched by the ending, with Bobby once again on a truck being driven away from the audience.

It's quite interesting to read reviews or comments on the movie over time as the perception of the various characters and their actions changes pretty dramatically from viewer to viewer. Just look at Ebert's disturbing 1970 review of the film compared to his later revisal for an example of that change over time. His view of the women in the film comes much closer to Bobby's own likely perception in the earlier review, while the later one pulls back more from identification, while maintaining similar enthusiasm. I've read reviews that find Catherine a phony, and those that see her as being the only one to provide insight into Bobby. Rayette has been deemed a pretender, redneck and beneath Bobby, and also found support from some who see Bobby as the asshole in the relationship. It's hard not to think of that as a strength of the film in many ways, where the main characters aren't easily classifiable in identical terms for everyone, but where enough information and activity is provided to allow for differing possibilities of interpreting actions that aren't given express definition. It's a movie that relies heavily on suggestion for how one responds to events, and that is a much more powerful method than demand of single defining answers.

It works a bit less well with Palm, the filth obsessed seemingly lesbian Bobby and Rayette pick up, and so too for Samia, the lecturing "celibate", where their speeches slide into excess and absurdity, denying them on the surface the same kind of ambiguity the main characters share. But that isn't to suggest they are without purpose, both being outside Bobby's interest as viable sex partners by definition, and each providing some perhaps apt commentary on Bobby's own actions once he loses his temper with Samia. Her talk of aggression and men plays out with Bobby attacking Spicer, in a hypocritical moment given his accusing Samia of knowing nothing about class the moment before (not to mention his own relationship with Rayette). Bobby's rant about shit and his final flight north in the truck echoes Palm's rants about Man too. The entire sequence from Samia's arrival through the fight is the coming together and ultimate destruction of Bobby's split view of himself, giving lie, in a sense, to his delicately balanced conception of his place. It too has something of an earlier match in his brief blow up at Elton, foreshadowing the later loss of self control.

For me, it really is in Bobby's chase of Catherine and finding Partita with Spicer that the movie comes together, where Bobby loses perspective and the film is freed to show events in the moment, with Bobby and "reality" aligned. His subsequent conversations and departure then, with that as a base, fit much better into a more open perceptual frame, where Bobby is simply reacting, not directing events, in a manner of speaking. The drive "home" with Rayette is where Bobby's perception starts threatening to weigh down on the film again, which is aborted by his fleeing north and abandoning Rayette and his belongings with the repeating mantra of "I'm fine."

It works, but isn't quite as effective as I'd hoped in a weird way as the film has this beautiful structure, where the first part of the movie with Rayette, Elton, and Stoney, is balanced against his return to his childhood home with Catherine, Carl, and Partita providing echoing variation to the earlier trio, but with his father silently present acting as anchor to the actions (and then all of it blows up in the final section when Rayette comes to the manor and Bobby;s two worlds collide in a sense). Most of the film is caught up with Bobby feeling the pressure from and/or responding to women he is around, with his relationship with his father seeming to provide motivation or meaning to those interactions in some unclear way. With Elton Bobby is more or less at ease, up until Elton suggests Bobby might do well to settle down with Rayette, which causes Bobby to deny his connection or similarity to Elton. (A moment which is wonderfully undercut by the absurd capture of Elton by police for robbery, acting as a shock to Bobby's perceptions.)

My problem with the film, such as it is, comes, oddly enough perhaps, from Carl not being more convincingly defined. While Carl acts as a sort of possible alternative for Bobby, sorry, Robert, he doesn't carry the same feeling of genuineness as Elton does, seeming more caricature like Palm and Samia than other possible life. His lack of definition then affects Catherine and her response to Bobby given the relationship between her and Carl lacks purchase. While this is reasonable from Bobby's perspective, it, to me, harms the reading of Catherine as a character and lessens suggestion about the alternative Bobby sought to avoid, but is also drawn to through Catherine. If there is a weakness in the film for me, it is in the conception of Carl and how that subtly shifts our reaction to Bobby's choice and the dominance of his overall perception.

Anyway, that's likely enough for now, but feel free to push back against that argument since it's a film worthy of more discussion from all angles, and it also isn't something I'm so determined to be "right" about that I'm beyond convincing as I did like the movie great deal, just wanted a touch more from it in the end.

posted by gusottertrout at 2:18 AM on June 20, 2017 [3 favorites]

Without that, the movie evokes all too clearly a sense of Bobby's perspective, a feeling of unmatched demands and wants, from himself outwards and from others towards him. The relentlessness of those perceived demands on his own vaguely articulated, and likely vaguely understood, set of values makes the movie oppressive, requiring some sense of at least momentary relief to assess where the weight of the problem is coming from. My initial feeling was that the movie was too aligned with Bobby and didn't allow for enough space to see the other characters outside his perspective, which created some unwelcome feeling of his perspective being validated, inhibiting deeper assessment by way of caricature. That left the ending of the film at the gas station feeling a bit off as the tonal shift didn't feel entirely congruent with what came before.

On rewatch, I've modified my thinking a bit as I found the film much more successful than on my first viewing, but still with some lingering dissatisfaction over the dominating perspective of the film and its seeming effect on how one sees Bobby and the other characters.

It's now easier to appreciate the more necessary elements of the effect of adopting Bobby's perspective as the dominant tone for the movie, with it providing a meaningful tension to almost every scene, starting from Bobby first entering the house he shares with Rayette, up until the conversation with Samia at his childhood home, with only the momentary diversion of his piano playing on the back of the truck providing the distance to see Bobby rather than be caught up in his emotional state. That latter scene being matched by the ending, with Bobby once again on a truck being driven away from the audience.

It's quite interesting to read reviews or comments on the movie over time as the perception of the various characters and their actions changes pretty dramatically from viewer to viewer. Just look at Ebert's disturbing 1970 review of the film compared to his later revisal for an example of that change over time. His view of the women in the film comes much closer to Bobby's own likely perception in the earlier review, while the later one pulls back more from identification, while maintaining similar enthusiasm. I've read reviews that find Catherine a phony, and those that see her as being the only one to provide insight into Bobby. Rayette has been deemed a pretender, redneck and beneath Bobby, and also found support from some who see Bobby as the asshole in the relationship. It's hard not to think of that as a strength of the film in many ways, where the main characters aren't easily classifiable in identical terms for everyone, but where enough information and activity is provided to allow for differing possibilities of interpreting actions that aren't given express definition. It's a movie that relies heavily on suggestion for how one responds to events, and that is a much more powerful method than demand of single defining answers.

It works a bit less well with Palm, the filth obsessed seemingly lesbian Bobby and Rayette pick up, and so too for Samia, the lecturing "celibate", where their speeches slide into excess and absurdity, denying them on the surface the same kind of ambiguity the main characters share. But that isn't to suggest they are without purpose, both being outside Bobby's interest as viable sex partners by definition, and each providing some perhaps apt commentary on Bobby's own actions once he loses his temper with Samia. Her talk of aggression and men plays out with Bobby attacking Spicer, in a hypocritical moment given his accusing Samia of knowing nothing about class the moment before (not to mention his own relationship with Rayette). Bobby's rant about shit and his final flight north in the truck echoes Palm's rants about Man too. The entire sequence from Samia's arrival through the fight is the coming together and ultimate destruction of Bobby's split view of himself, giving lie, in a sense, to his delicately balanced conception of his place. It too has something of an earlier match in his brief blow up at Elton, foreshadowing the later loss of self control.

For me, it really is in Bobby's chase of Catherine and finding Partita with Spicer that the movie comes together, where Bobby loses perspective and the film is freed to show events in the moment, with Bobby and "reality" aligned. His subsequent conversations and departure then, with that as a base, fit much better into a more open perceptual frame, where Bobby is simply reacting, not directing events, in a manner of speaking. The drive "home" with Rayette is where Bobby's perception starts threatening to weigh down on the film again, which is aborted by his fleeing north and abandoning Rayette and his belongings with the repeating mantra of "I'm fine."

It works, but isn't quite as effective as I'd hoped in a weird way as the film has this beautiful structure, where the first part of the movie with Rayette, Elton, and Stoney, is balanced against his return to his childhood home with Catherine, Carl, and Partita providing echoing variation to the earlier trio, but with his father silently present acting as anchor to the actions (and then all of it blows up in the final section when Rayette comes to the manor and Bobby;s two worlds collide in a sense). Most of the film is caught up with Bobby feeling the pressure from and/or responding to women he is around, with his relationship with his father seeming to provide motivation or meaning to those interactions in some unclear way. With Elton Bobby is more or less at ease, up until Elton suggests Bobby might do well to settle down with Rayette, which causes Bobby to deny his connection or similarity to Elton. (A moment which is wonderfully undercut by the absurd capture of Elton by police for robbery, acting as a shock to Bobby's perceptions.)

My problem with the film, such as it is, comes, oddly enough perhaps, from Carl not being more convincingly defined. While Carl acts as a sort of possible alternative for Bobby, sorry, Robert, he doesn't carry the same feeling of genuineness as Elton does, seeming more caricature like Palm and Samia than other possible life. His lack of definition then affects Catherine and her response to Bobby given the relationship between her and Carl lacks purchase. While this is reasonable from Bobby's perspective, it, to me, harms the reading of Catherine as a character and lessens suggestion about the alternative Bobby sought to avoid, but is also drawn to through Catherine. If there is a weakness in the film for me, it is in the conception of Carl and how that subtly shifts our reaction to Bobby's choice and the dominance of his overall perception.

Anyway, that's likely enough for now, but feel free to push back against that argument since it's a film worthy of more discussion from all angles, and it also isn't something I'm so determined to be "right" about that I'm beyond convincing as I did like the movie great deal, just wanted a touch more from it in the end.

posted by gusottertrout at 2:18 AM on June 20, 2017 [3 favorites]

I've read reviews that find Catherine a phony, and those that see her as being the only one to provide insight into Bobby. Rayette has been deemed a pretender, redneck and beneath Bobby, and also found support from some who see Bobby as the asshole in the relationship. It's hard not to think of that as a strength of the film in many ways, where the main characters aren't easily classifiable in identical terms for everyone, but where enough information and activity is provided to allow for differing possibilities of interpreting actions that aren't given express definition. It's a movie that relies heavily on suggestion for how one responds to events, and that is a much more powerful method than demand of single defining answers.

Yeah; you get the sense that if you saw it with a mixed group of people, a lot of preconceptions and biases concerning class and gender might quickly emerge in the post-movie coffee-shop discussion.

Most of the film is caught up with Bobby feeling the pressure from and/or responding to women he is around, with his relationship with his father seeming to provide motivation or meaning to those interactions in some unclear way.

And yet, IIRC, he barely seems to acknowledge Palm. You did point out that it could have to do with the sexual access thing, like the other lecturing character Samia. But he DOES confront Samia. On my first watch, I guessed that the Palm stuff might have been meant as just one more pallet of psychological pressure loaded onto Bobby—probably because I expected him to snap, because it's Jack Nicholson!—and, if that's the "correct" read, then that could be why he snapped at Samia. But if so, it's weird that the film doesn't really even hint that Palm is getting to him. I mean, it's Rayette that actually confronts her.

So maybe that supports what you're saying about the structure not quite being as tight as we might like it to be. Unless that was deliberate, and part of the whole proto-indie factor. I mean, it IS classified as a "road movie," and all road movies need their strange digressions.

And not to beat that sequence into the ground, but when they drop off the hitchhikers, I couldn't get a read on whether this was meant as a comic early dropoff due to Bobby and Rayette getting sick of them (like what I'm pretty sure somebody did to Pee-Wee Herman at some point), or whether they'd reached their destination. The shot was too long to parse the hitchhikers' reactions. Maybe I missed some key detail, but it struck me at the time as needlessly opaque, and not even in a forgivable indie sense. Probably a minor point.

If there is a weakness in the film for me, it is in the conception of Carl and how that subtly shifts our reaction to Bobby's choice and the dominance of his overall perception.

I see what you mean, and now that you point it out, I think I might agree. While watching, I sort of internally-mentally-simplified Carl's characterization under a general "phony" umbrella, since this movie (and this era, to an extent) seemed concerned with phoniness and genuineness. And at first I expected Carl to be a more major character, to play a more pivotal role in however the film was to end. But the way Bobby basically conned him into disappearing for a while made Carl seem like almost more of a hapless innocent, which might fit in some way with the family's isolation. Still, you'd think—given how central Bobby's background is to everything—we might have gotten to know Carl better. OTOH, given what we DO learn, more time spent on their contrast might have just ended up as that whole "very different brothers" trope, which would've been too on-the-nose, too cliche.

In any case, I think you're right that the film seems to pretty much use Carl as a means of providing characterization/motivation for Catherine, though whether it does so in a suitable or an icky way is another matter.

posted by CheesesOfBrazil at 3:24 AM on June 23, 2017

Yeah; you get the sense that if you saw it with a mixed group of people, a lot of preconceptions and biases concerning class and gender might quickly emerge in the post-movie coffee-shop discussion.

Most of the film is caught up with Bobby feeling the pressure from and/or responding to women he is around, with his relationship with his father seeming to provide motivation or meaning to those interactions in some unclear way.

And yet, IIRC, he barely seems to acknowledge Palm. You did point out that it could have to do with the sexual access thing, like the other lecturing character Samia. But he DOES confront Samia. On my first watch, I guessed that the Palm stuff might have been meant as just one more pallet of psychological pressure loaded onto Bobby—probably because I expected him to snap, because it's Jack Nicholson!—and, if that's the "correct" read, then that could be why he snapped at Samia. But if so, it's weird that the film doesn't really even hint that Palm is getting to him. I mean, it's Rayette that actually confronts her.

So maybe that supports what you're saying about the structure not quite being as tight as we might like it to be. Unless that was deliberate, and part of the whole proto-indie factor. I mean, it IS classified as a "road movie," and all road movies need their strange digressions.

And not to beat that sequence into the ground, but when they drop off the hitchhikers, I couldn't get a read on whether this was meant as a comic early dropoff due to Bobby and Rayette getting sick of them (like what I'm pretty sure somebody did to Pee-Wee Herman at some point), or whether they'd reached their destination. The shot was too long to parse the hitchhikers' reactions. Maybe I missed some key detail, but it struck me at the time as needlessly opaque, and not even in a forgivable indie sense. Probably a minor point.

If there is a weakness in the film for me, it is in the conception of Carl and how that subtly shifts our reaction to Bobby's choice and the dominance of his overall perception.

I see what you mean, and now that you point it out, I think I might agree. While watching, I sort of internally-mentally-simplified Carl's characterization under a general "phony" umbrella, since this movie (and this era, to an extent) seemed concerned with phoniness and genuineness. And at first I expected Carl to be a more major character, to play a more pivotal role in however the film was to end. But the way Bobby basically conned him into disappearing for a while made Carl seem like almost more of a hapless innocent, which might fit in some way with the family's isolation. Still, you'd think—given how central Bobby's background is to everything—we might have gotten to know Carl better. OTOH, given what we DO learn, more time spent on their contrast might have just ended up as that whole "very different brothers" trope, which would've been too on-the-nose, too cliche.

In any case, I think you're right that the film seems to pretty much use Carl as a means of providing characterization/motivation for Catherine, though whether it does so in a suitable or an icky way is another matter.

posted by CheesesOfBrazil at 3:24 AM on June 23, 2017

I didn't see this movie until I was in my 30s; I think Nicholson's character reminded me a little too much of a my Dad, or more perhaps my uncle. (Both gone.)

This movie is a study of an asshole. It's fascinating, sort of, because at least we find out in reverse what has created Nicholson's character.

But still, he's an asshole. Or, at least, a noisy coward. And so I find myself recommending this incredible movie, but never really wanting to talk or think about it. It's like, if I do that, then Dupea wins.

posted by fleacircus at 2:22 AM on July 1, 2017 [1 favorite]

This movie is a study of an asshole. It's fascinating, sort of, because at least we find out in reverse what has created Nicholson's character.

But still, he's an asshole. Or, at least, a noisy coward. And so I find myself recommending this incredible movie, but never really wanting to talk or think about it. It's like, if I do that, then Dupea wins.

posted by fleacircus at 2:22 AM on July 1, 2017 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

It sounds like Eastman had consistent problems with her writing being respected by her male colleagues, and she had one flop that basically sabotaged her career, which is a great example of how quickly a woman's career will be submarined when every man involved gets out scot-free (the film was Man Trouble, and neither star Jack Nicholson nor director Bob Rafelson had trouble shrugging it off, but it ended Eastman's career.)

I think she deserves a revival. I haven't seen her film Puzzle of a Downfall Child, based on her own experiences as a former model, but it sounds terrific. The writing in Five Easy Pieces should have solidified her reputation as a major league screenwriter, and she she is almost never mentioned and barely remembered.

posted by maxsparber at 8:28 AM on June 14, 2017 [8 favorites]