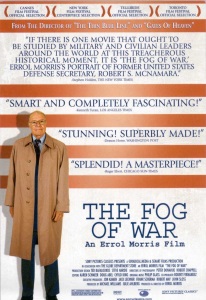

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003)

March 7, 2018 6:37 PM - Subscribe

The story of America as seen through the eyes of the former Secretary of Defense under President John F. Kennedy and President Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara.

AV Club: Subtitled "Eleven Lessons From The Life Of Robert S. McNamara," The Fog Of War neither damns nor exonerates its subject, but instead allows him the space to account for his actions. Whether viewers find his reflections candid, evasive, or somewhere in between is entirely up to them. Some have complained that Morris lets him off too easy, but great journalism isn't about nailing someone; it's about evoking the truth in all its thorny contradictions, and few can honestly claim to have a handle on McNamara, not least the man himself. With his unmistakable blend of intellectual curiosity and virtuosic technique, Morris (The Thin Blue Line, Fast, Cheap & Out Of Control) uses McNamara's involvement in three major conflicts as a window into larger issues of war and foreign policy in the second half of the 20th century. Moving in precise time to Philip Glass' propulsive score, the film zigzags freely through McNamara's personal and professional history, starting with the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then doubling back to his childhood, his roles in WWII and the Ford Motor Company, his relationship to JFK and LBJ, and, finally, the Vietnam War.

Slate: Some of the lessons he cites in this film will be astonishing to anyone who remembers his arrogance in power. The biggest eye-opener may be when McNamara says, "Rationality will not save us"—a truism to most people, but the precise opposite of what he would have contended 40 years ago. He also warns against using military power unilaterally (a point as relevant to President Bush and Donald Rumsfeld in Iraq as to McNamara himself in Vietnam). And in the film's most searing moment, he likens himself to a war criminal for the massive firebombings that he and Gen. Curtis LeMay planned during WWII; the raids over Tokyo killed 100,000 civilians in a single night.

Later in the film, McNamara refuses to discuss the responsibility he might bear for the damage wreaked in Vietnam. Nor does he want to talk about why, though he came to regret the war, he failed to speak out against it after he left office. Still, his brooding over the ravages he helped inflict in WWII—"the good war"—may suggest the scope of his later agonies; in any case, it reveals a far more introspective McNamara than we've ever seen.

Roger Ebert: McNamara is both forthright and elusive. He talks about a Quaker who burned himself to death below the windows of his office in the Pentagon and finds his sacrifice somehow in the same spirit as his own thinking -- but it is true he could have done more to try to end the war, and did not, and will not say why he did not, although now he clearly wishes he had.

He will also not say he is sorry, even though Morris prompts him; maybe he's too proud, but I get the feeling it's more a case of not wanting to make a useless gesture that could seem hypocritical. His final words in the film make it clear there are some places he is simply not prepared to go.

Salon: The problem with "The Fog of War" isn't one of balance. Barring the convictions people already hold about the former secretary of defense, it would be very hard to come away from the movie feeling it either fully condemns or fully exculpates McNamara. The man himself is both distant and frequently emotional (his voice breaks with tears several times in the course of the film), willing to examine his actions -- not just in Vietnam but during World War II and the Cuban missile crisis -- and stubbornly unwilling to issue a mea culpa (that itself seems both arrogant and humble). The McNamara we see in "The Fog of War" is as much of a pickle as he's always been, seeming both searching and blind, hounded and complacent. He isn't haughty and dismissive in the way that still makes Henry Kissinger so hateful. McNamara's actions may fill us with repugnance, but you'd have to blindly hate the man not to acknowledge his intelligence or his willingness to talk, often bluntly, about his time in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

If Morris had simply concluded that he was dealing with an enigma, this investigation into McNamara's psyche might have been intellectually satisfying. But, as in his other films, Morris feels much more concerned with aesthetics than with moral or historical questions.

LATimes: Morris early on decided to interview only McNamara for this film, and the former secretary spent 23 hours facing the director's Interrotron, a machine that makes subjects seem to be looking directly into the camera. Articulate, confident, forceful and compelling, McNamara is not one to be at a loss for words.

The danger of that decision, the director himself admitted in Cannes, is, " 'How does that become impartial?' The answer is, it doesn't -- it doesn't even have the pretense. What it does is take you inside someone's head. It's part dream, part history, part self-analysis, part self-justification, part mystery."

Slant: Is McNamara the soulless technocrat he has long been accused of being? Is he the bearer of a deep and terrible guilt? To its lasting credit, The Fog of War does not provide easy answers. Its portrait of McNamara is one of a man who, now in his autumnal years, finds himself looking back at a life that shared a terrible intimacy with the history of the world. The public ramifications of that life are left open to debate. Morris maintains his usual ironic distance, both wary of and fascinated by his subject, only it’s clear that this time Morris’s interest is far more sympathetically inclined.

Morris allows McNamara the dignity of his memories, yet never allows the viewer to forget the deeply troubling moral questions—both on a personal and societal level—bound to those memories.

NYTimes: None of the documentary's lessons can be described as reassuring. ''Believing and seeing are both often wrong,'' one says. ''Rationality will not save us,'' goes another. The final and saddest lesson is delivered by Mr. McNamara with a rueful, you-know-what-I-mean smile:'' ''You can't change human nature.''

Trailer

Full documentary on Vimeo

Making History: Errol Morris, Robert McNamara and The Fog of War

errolmorris.com

Terry Gross Interview of Errol Morris on The Fog of War

Errol Morris: McNamara After “The Fog of War”

AV Club: Subtitled "Eleven Lessons From The Life Of Robert S. McNamara," The Fog Of War neither damns nor exonerates its subject, but instead allows him the space to account for his actions. Whether viewers find his reflections candid, evasive, or somewhere in between is entirely up to them. Some have complained that Morris lets him off too easy, but great journalism isn't about nailing someone; it's about evoking the truth in all its thorny contradictions, and few can honestly claim to have a handle on McNamara, not least the man himself. With his unmistakable blend of intellectual curiosity and virtuosic technique, Morris (The Thin Blue Line, Fast, Cheap & Out Of Control) uses McNamara's involvement in three major conflicts as a window into larger issues of war and foreign policy in the second half of the 20th century. Moving in precise time to Philip Glass' propulsive score, the film zigzags freely through McNamara's personal and professional history, starting with the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then doubling back to his childhood, his roles in WWII and the Ford Motor Company, his relationship to JFK and LBJ, and, finally, the Vietnam War.

Slate: Some of the lessons he cites in this film will be astonishing to anyone who remembers his arrogance in power. The biggest eye-opener may be when McNamara says, "Rationality will not save us"—a truism to most people, but the precise opposite of what he would have contended 40 years ago. He also warns against using military power unilaterally (a point as relevant to President Bush and Donald Rumsfeld in Iraq as to McNamara himself in Vietnam). And in the film's most searing moment, he likens himself to a war criminal for the massive firebombings that he and Gen. Curtis LeMay planned during WWII; the raids over Tokyo killed 100,000 civilians in a single night.

Later in the film, McNamara refuses to discuss the responsibility he might bear for the damage wreaked in Vietnam. Nor does he want to talk about why, though he came to regret the war, he failed to speak out against it after he left office. Still, his brooding over the ravages he helped inflict in WWII—"the good war"—may suggest the scope of his later agonies; in any case, it reveals a far more introspective McNamara than we've ever seen.

Roger Ebert: McNamara is both forthright and elusive. He talks about a Quaker who burned himself to death below the windows of his office in the Pentagon and finds his sacrifice somehow in the same spirit as his own thinking -- but it is true he could have done more to try to end the war, and did not, and will not say why he did not, although now he clearly wishes he had.

He will also not say he is sorry, even though Morris prompts him; maybe he's too proud, but I get the feeling it's more a case of not wanting to make a useless gesture that could seem hypocritical. His final words in the film make it clear there are some places he is simply not prepared to go.

Salon: The problem with "The Fog of War" isn't one of balance. Barring the convictions people already hold about the former secretary of defense, it would be very hard to come away from the movie feeling it either fully condemns or fully exculpates McNamara. The man himself is both distant and frequently emotional (his voice breaks with tears several times in the course of the film), willing to examine his actions -- not just in Vietnam but during World War II and the Cuban missile crisis -- and stubbornly unwilling to issue a mea culpa (that itself seems both arrogant and humble). The McNamara we see in "The Fog of War" is as much of a pickle as he's always been, seeming both searching and blind, hounded and complacent. He isn't haughty and dismissive in the way that still makes Henry Kissinger so hateful. McNamara's actions may fill us with repugnance, but you'd have to blindly hate the man not to acknowledge his intelligence or his willingness to talk, often bluntly, about his time in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

If Morris had simply concluded that he was dealing with an enigma, this investigation into McNamara's psyche might have been intellectually satisfying. But, as in his other films, Morris feels much more concerned with aesthetics than with moral or historical questions.

LATimes: Morris early on decided to interview only McNamara for this film, and the former secretary spent 23 hours facing the director's Interrotron, a machine that makes subjects seem to be looking directly into the camera. Articulate, confident, forceful and compelling, McNamara is not one to be at a loss for words.

The danger of that decision, the director himself admitted in Cannes, is, " 'How does that become impartial?' The answer is, it doesn't -- it doesn't even have the pretense. What it does is take you inside someone's head. It's part dream, part history, part self-analysis, part self-justification, part mystery."

Slant: Is McNamara the soulless technocrat he has long been accused of being? Is he the bearer of a deep and terrible guilt? To its lasting credit, The Fog of War does not provide easy answers. Its portrait of McNamara is one of a man who, now in his autumnal years, finds himself looking back at a life that shared a terrible intimacy with the history of the world. The public ramifications of that life are left open to debate. Morris maintains his usual ironic distance, both wary of and fascinated by his subject, only it’s clear that this time Morris’s interest is far more sympathetically inclined.

Morris allows McNamara the dignity of his memories, yet never allows the viewer to forget the deeply troubling moral questions—both on a personal and societal level—bound to those memories.

NYTimes: None of the documentary's lessons can be described as reassuring. ''Believing and seeing are both often wrong,'' one says. ''Rationality will not save us,'' goes another. The final and saddest lesson is delivered by Mr. McNamara with a rueful, you-know-what-I-mean smile:'' ''You can't change human nature.''

Trailer

Full documentary on Vimeo

Making History: Errol Morris, Robert McNamara and The Fog of War

errolmorris.com

Terry Gross Interview of Errol Morris on The Fog of War

Errol Morris: McNamara After “The Fog of War”

Errol Morris the person, while definitely a force for good, has started to get to me a bit just due to my binging on interviews etc with him. He seems to just keep talking once he gets started, and seems to definitly believe in his own brilliance. But as I said, he is a force for good and has certainly earned his high self esteem.

Anyway, I thought this film pulled off something really unusual of showing the beauty of someone/something horrible. Due in no small part to the soundtrack, the mood of this movie just transcends the subject to seem to be about something bigger in terms of human nature, history, self deception, etc. As an opinionated documentary, it's pretty flawless, letting McNamara do all the work of indicting himself. I can only imagine what this movie is like for people who lived through the war and remember him from then - I was born in '74 so this is all history to me. But just as an aesthetic piece of art, the editing and sound design is just really masterful and affecting.

posted by latkes at 9:57 PM on March 7, 2018

Anyway, I thought this film pulled off something really unusual of showing the beauty of someone/something horrible. Due in no small part to the soundtrack, the mood of this movie just transcends the subject to seem to be about something bigger in terms of human nature, history, self deception, etc. As an opinionated documentary, it's pretty flawless, letting McNamara do all the work of indicting himself. I can only imagine what this movie is like for people who lived through the war and remember him from then - I was born in '74 so this is all history to me. But just as an aesthetic piece of art, the editing and sound design is just really masterful and affecting.

posted by latkes at 9:57 PM on March 7, 2018

I saw this in the theaters. I thought it was good & interesting.

Like Carillon said in his comment, though, my experience discussing McNamara with my parents (here my father) hit a nerve. I would've been in my early '30s at the time of the conversation. My dad was in his late twenties during the McNamara era.

He simply didn't want to talk about it. He *hated* McNamara. The bits of self reflection McNamara showed in the movie made him even worse--basically confirmed he was lying to the American people all along and didn't give a damn about letting Americans or Vietnamese die for no reason.

posted by mark k at 10:11 PM on March 7, 2018 [2 favorites]

Like Carillon said in his comment, though, my experience discussing McNamara with my parents (here my father) hit a nerve. I would've been in my early '30s at the time of the conversation. My dad was in his late twenties during the McNamara era.

He simply didn't want to talk about it. He *hated* McNamara. The bits of self reflection McNamara showed in the movie made him even worse--basically confirmed he was lying to the American people all along and didn't give a damn about letting Americans or Vietnamese die for no reason.

posted by mark k at 10:11 PM on March 7, 2018 [2 favorites]

I mean I guess I took it as a given that McNamara was a ghoul - a war criminal - a man who had done evil on a massive scale. And I thought the movie did too?

posted by latkes at 10:18 PM on March 7, 2018

posted by latkes at 10:18 PM on March 7, 2018

James Carroll said at a reading that his mother claimed that McNamara's family took the soup.

posted by brujita at 9:05 AM on March 8, 2018

posted by brujita at 9:05 AM on March 8, 2018

I really loved this movie, I think it's morris' best.

My parents also had a similar reaction, characterising mcnamara as a brilliant monster.

posted by smoke at 12:30 AM on March 9, 2018

My parents also had a similar reaction, characterising mcnamara as a brilliant monster.

posted by smoke at 12:30 AM on March 9, 2018

As the child of Republicans, I would have loved to have known their opinion of this movie and McNamara post-Vietnam. Dad was involved in the SE Asia front only as a member of flight crews, so whatever his planes did or dropped, he never saw first hand.

As both my parents are long gone, I can only imagine their reactions to our world post-Sept 11. As I've said likely here and elsewhere, I'm only thankful that they're not around to witness what we've become.

posted by computech_apolloniajames at 6:35 PM on March 10, 2018

As both my parents are long gone, I can only imagine their reactions to our world post-Sept 11. As I've said likely here and elsewhere, I'm only thankful that they're not around to witness what we've become.

posted by computech_apolloniajames at 6:35 PM on March 10, 2018

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Carillon at 8:42 PM on March 7, 2018 [3 favorites]