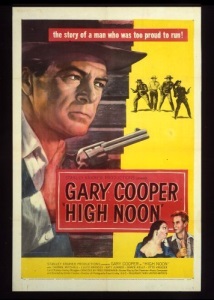

High Noon (1952)

July 9, 2018 7:08 PM - Subscribe

A town Marshal, despite the disagreements of his newlywed bride and the townspeople around him, must face a gang of deadly killers alone at high noon when the gang leader, an outlaw he sent up years ago, arrives on the noon train.

Empire: Gary Cooper, the top-billed star, was a familiar cowboy face with a western drawl to match, but he was in his third decade as a revered movie star, a little elderly for the rough stuff and with acting chops to spare. The innovation of High Noon is that it's significant, but not big. Its understated but unforgettable opening — three bad men (Lee Van Cleef, Robert Wilkie, Sheb "Flying Purple People Eater" Wooley) at the station, waiting around on a Sunday morning while Tex Hitter's ballad explains the plot — prefaces a movie that takes place almost in real time, from mid-morning to just after midday, and never strays far from the main street of the western township of Hadleyville.

In the 1940s and 50s, high-stakes westerns were inclined to the epic, with Technicolor mesas and deserts and hordes of cowboy and Indian extras, but High Noon could be a TV script. Its style is like that character-and-suspense-based drama which would evolve when American television was broadcast live from New York. The simmering resentment of sidelined Deputy Pell (Lloyd Bridges) that his soon-to-be-ex boss, retiring Marshal Will Kane (Cooper), didn't get him appointed the new law in town pays off with a fistfight at the halfway point, but otherwise the film is all about suspense rather than action.

AV Club: In an Oscar-winning turn, Cooper plays a tormented lawman in the midst of the most dramatic 90 minutes of his life. In real time, Cooper marries Quaker Grace Kelly, tangles with cocky, callow deputy Lloyd Bridges, confronts the antagonism and ambivalence of his constituents, and stares down a revenge-hungry ex-con who's heading back to town on a train scheduled to arrive at high noon. The soon-to-be-blacklisted screenwriter Carl Foreman saw Cooper's plight as an allegory for Hollywood's shameful acquiescence to McCarthyism and these are the most subtle aspects of a generally unsubtle film.

There's "symbolism" and then there's "SYMBOLISM!" With a ham-fisted earnestness befitting a Stanley Kramer production, High Noon director Fred Zinneman subscribes to the second variety. It's unapologetically a Western of ideas, but those ideas would be much more palatable if Foreman's script didn't constantly beat audiences over the head with them.

Cinephilia and Beyond: High Noon’s screenwriter Carl Foreman was summoned to Washington during filming to be questioned about his Communist activities (he was a member, but left the party 10 years prior to this film), reportedly returning to the set frightened but inspired. He wrote in a series of scenes that reflected his own experience with the HUAC and the fact that he was soon to be blacklisted gave him vigor to make the most out of this story. There are, however, no traces whatsoever of Communist propaganda in the film: only strong feelings of disillusionment, sorrow and disappointment of a man left by his friends and colleagues to be eaten up by a malignant force threatening to disrupt a carefully built community of democracy and respect.

Trailer

Filming locations

Original 1952 Variety review

The Tao of Gary Cooper

High Noon’s Secret Backstory

“Do Not Forsake Me: The Ballad of High Noon” and the Rise of the Movie Theme Song

Empire: Gary Cooper, the top-billed star, was a familiar cowboy face with a western drawl to match, but he was in his third decade as a revered movie star, a little elderly for the rough stuff and with acting chops to spare. The innovation of High Noon is that it's significant, but not big. Its understated but unforgettable opening — three bad men (Lee Van Cleef, Robert Wilkie, Sheb "Flying Purple People Eater" Wooley) at the station, waiting around on a Sunday morning while Tex Hitter's ballad explains the plot — prefaces a movie that takes place almost in real time, from mid-morning to just after midday, and never strays far from the main street of the western township of Hadleyville.

In the 1940s and 50s, high-stakes westerns were inclined to the epic, with Technicolor mesas and deserts and hordes of cowboy and Indian extras, but High Noon could be a TV script. Its style is like that character-and-suspense-based drama which would evolve when American television was broadcast live from New York. The simmering resentment of sidelined Deputy Pell (Lloyd Bridges) that his soon-to-be-ex boss, retiring Marshal Will Kane (Cooper), didn't get him appointed the new law in town pays off with a fistfight at the halfway point, but otherwise the film is all about suspense rather than action.

AV Club: In an Oscar-winning turn, Cooper plays a tormented lawman in the midst of the most dramatic 90 minutes of his life. In real time, Cooper marries Quaker Grace Kelly, tangles with cocky, callow deputy Lloyd Bridges, confronts the antagonism and ambivalence of his constituents, and stares down a revenge-hungry ex-con who's heading back to town on a train scheduled to arrive at high noon. The soon-to-be-blacklisted screenwriter Carl Foreman saw Cooper's plight as an allegory for Hollywood's shameful acquiescence to McCarthyism and these are the most subtle aspects of a generally unsubtle film.

There's "symbolism" and then there's "SYMBOLISM!" With a ham-fisted earnestness befitting a Stanley Kramer production, High Noon director Fred Zinneman subscribes to the second variety. It's unapologetically a Western of ideas, but those ideas would be much more palatable if Foreman's script didn't constantly beat audiences over the head with them.

Cinephilia and Beyond: High Noon’s screenwriter Carl Foreman was summoned to Washington during filming to be questioned about his Communist activities (he was a member, but left the party 10 years prior to this film), reportedly returning to the set frightened but inspired. He wrote in a series of scenes that reflected his own experience with the HUAC and the fact that he was soon to be blacklisted gave him vigor to make the most out of this story. There are, however, no traces whatsoever of Communist propaganda in the film: only strong feelings of disillusionment, sorrow and disappointment of a man left by his friends and colleagues to be eaten up by a malignant force threatening to disrupt a carefully built community of democracy and respect.

Trailer

Filming locations

Original 1952 Variety review

The Tao of Gary Cooper

High Noon’s Secret Backstory

“Do Not Forsake Me: The Ballad of High Noon” and the Rise of the Movie Theme Song

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by tobascodagama at 9:39 AM on July 10, 2018