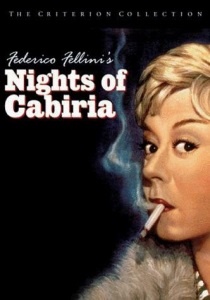

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

February 29, 2024 12:06 PM - Subscribe

A waifish prostitute wanders the streets of Rome looking for true love but finds only heartbreak.

In the fifth of their immortal collaborations, Federico Fellini and the exquisitely expressive Giulietta Masina completed the creation of one of the most indelible characters in all of cinema: Cabiria, an irrepressible, fiercely independent sex worker who, as she moves through the sea of Rome’s humanity, through adversity and heartbreak, must rely on herself—and her own indomitable spirit—to stay standing. Winner of the best actress prize at Cannes for Masina and the Academy Award for best foreign-language film, Nights of Cabiria brought the early, neorealist-influenced phase of Fellini’s career to a transcendent close with its sublimely heartbreaking yet hopeful final image, which embodies, perhaps more than any other in the director’s body of work, the blend of the bitter and the sweet that define his vision of the world.

Dilys Powell: And a varied but logically linked series of incidents shows her true nature. A farcical contretemps with a high-class client; a passage of naive religious fervour and disillusion; a dreadful public humiliation inflicted by a hypnotist - one of the cruel jokers who infest the stage in Fellini's world: impudent or cowed, childishly gloating in a moment of triumph or pathetically crushed by treachery, Cabiria betrays her deep helplessness. The plot is not a catalogue of things which happen to her, it is a catalogue of things which happen because she is what she is. The story does not draw a character; the character is the story.

...

But Cabiria is the one we know, the one we mind about. I have heard it said that Giuletta Masina portrait in monotonous, and I should not deny that the little self-depreciatory grimaces are, in the early scenes, repetitive. Why shouldn't they be? Human being behave repetitively; only actors change their tune. What Fellini and Masina give us is not a realistic portrait, not a piece of romanticising either; it is the essence of the immortally hopeful, eternally cheated, indestructible human sparrow. The figure is desolating, but it is funny too, for it recognises - as we should all of us recognise if we were honest - that the ridiculous lurks in the heart of tragedy. And Masina - like Chaplon, like nearly all the grand comics - shows it blossoming there.

Stephanie Zacharek: The little house belonging to the title character in Federico Fellini's "Nights of Cabiria" rises out of the landscape on the edge of a desolate yet oddly cheerful little Roman neighborhood, like one of the solitary, boxy buildings that dot the horizon in a Krazy Kat cartoon. It's a cube built out of something like stucco, with a curtain of beads hanging like a shimmer of fake rain in front of its simple door -- part jazzed-up fairy-tale cottage, part Spartan make-do dwelling. For its owner, the love-starved yet emotionally self-sufficient prostitute Cabiria, played by Giulietta Masina, in the role of her career, the house represents security and pride, a place to return to that's all her own, like the tiny studio apartment of any city working girl. But is the house meant to signify isolation as a protective measure, or the sense of feeling truly at home with oneself? Or both?

Lulu Wang: I’ve been thinking a lot about Cabiria recently, as I watch films that wrestle with violence through the victimization of their protagonists. These films seem to pose a relationship between cause and effect: look what the world has done to these people—it’s no wonder they’re driven to madness and violence. But is that an inevitability? Are we meant to point our finger at society and identify with the rage of the individual? Human character is developed out of circumstance—how a person is challenged and how she responds. Which characters, challenges, and responses do we deem worthy of glorification? And why?

Cabiria is a prostitute and, essentially, the village clown, derided for being both naive and profane. What she wants most is to be loved, and when she meets a man named Oscar, who tells her he wants nothing more than to love her, she believes him. She returns to her village, triumphant in the knowledge that she will leave for a new life with a man who loves her—an experience that, according to townspeople, she is not entitled to having. Cabiria is eager to believe in the good in the world, to hang onto hope. In the penultimate scene, she feels vindicated, buoyant with the belief that life is fair, and that, despite suffering, happiness comes along for everyone! Fellini lets the camera linger on Oscar’s face as he listens to Cabiria’s exultations, the sweat informing us of his deception and malice without a single word. As the wind shifts and Cabiria realizes the menace in Oscar’s silence, she suddenly asks him if he’s there to kill her. He answers her with more silence. It’s one of the most devastating scenes I’ve ever seen.

Trailer

In the fifth of their immortal collaborations, Federico Fellini and the exquisitely expressive Giulietta Masina completed the creation of one of the most indelible characters in all of cinema: Cabiria, an irrepressible, fiercely independent sex worker who, as she moves through the sea of Rome’s humanity, through adversity and heartbreak, must rely on herself—and her own indomitable spirit—to stay standing. Winner of the best actress prize at Cannes for Masina and the Academy Award for best foreign-language film, Nights of Cabiria brought the early, neorealist-influenced phase of Fellini’s career to a transcendent close with its sublimely heartbreaking yet hopeful final image, which embodies, perhaps more than any other in the director’s body of work, the blend of the bitter and the sweet that define his vision of the world.

Dilys Powell: And a varied but logically linked series of incidents shows her true nature. A farcical contretemps with a high-class client; a passage of naive religious fervour and disillusion; a dreadful public humiliation inflicted by a hypnotist - one of the cruel jokers who infest the stage in Fellini's world: impudent or cowed, childishly gloating in a moment of triumph or pathetically crushed by treachery, Cabiria betrays her deep helplessness. The plot is not a catalogue of things which happen to her, it is a catalogue of things which happen because she is what she is. The story does not draw a character; the character is the story.

...

But Cabiria is the one we know, the one we mind about. I have heard it said that Giuletta Masina portrait in monotonous, and I should not deny that the little self-depreciatory grimaces are, in the early scenes, repetitive. Why shouldn't they be? Human being behave repetitively; only actors change their tune. What Fellini and Masina give us is not a realistic portrait, not a piece of romanticising either; it is the essence of the immortally hopeful, eternally cheated, indestructible human sparrow. The figure is desolating, but it is funny too, for it recognises - as we should all of us recognise if we were honest - that the ridiculous lurks in the heart of tragedy. And Masina - like Chaplon, like nearly all the grand comics - shows it blossoming there.

Stephanie Zacharek: The little house belonging to the title character in Federico Fellini's "Nights of Cabiria" rises out of the landscape on the edge of a desolate yet oddly cheerful little Roman neighborhood, like one of the solitary, boxy buildings that dot the horizon in a Krazy Kat cartoon. It's a cube built out of something like stucco, with a curtain of beads hanging like a shimmer of fake rain in front of its simple door -- part jazzed-up fairy-tale cottage, part Spartan make-do dwelling. For its owner, the love-starved yet emotionally self-sufficient prostitute Cabiria, played by Giulietta Masina, in the role of her career, the house represents security and pride, a place to return to that's all her own, like the tiny studio apartment of any city working girl. But is the house meant to signify isolation as a protective measure, or the sense of feeling truly at home with oneself? Or both?

Lulu Wang: I’ve been thinking a lot about Cabiria recently, as I watch films that wrestle with violence through the victimization of their protagonists. These films seem to pose a relationship between cause and effect: look what the world has done to these people—it’s no wonder they’re driven to madness and violence. But is that an inevitability? Are we meant to point our finger at society and identify with the rage of the individual? Human character is developed out of circumstance—how a person is challenged and how she responds. Which characters, challenges, and responses do we deem worthy of glorification? And why?

Cabiria is a prostitute and, essentially, the village clown, derided for being both naive and profane. What she wants most is to be loved, and when she meets a man named Oscar, who tells her he wants nothing more than to love her, she believes him. She returns to her village, triumphant in the knowledge that she will leave for a new life with a man who loves her—an experience that, according to townspeople, she is not entitled to having. Cabiria is eager to believe in the good in the world, to hang onto hope. In the penultimate scene, she feels vindicated, buoyant with the belief that life is fair, and that, despite suffering, happiness comes along for everyone! Fellini lets the camera linger on Oscar’s face as he listens to Cabiria’s exultations, the sweat informing us of his deception and malice without a single word. As the wind shifts and Cabiria realizes the menace in Oscar’s silence, she suddenly asks him if he’s there to kill her. He answers her with more silence. It’s one of the most devastating scenes I’ve ever seen.

Trailer

I don't think so. There's nothing I would remember calling a tree house in the film!

posted by Carillon at 5:34 PM on February 29 [1 favorite]

posted by Carillon at 5:34 PM on February 29 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Carillon at 12:09 PM on February 29 [1 favorite]