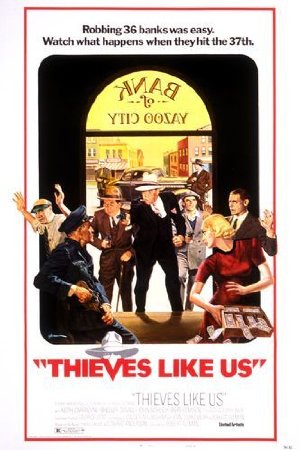

Thieves Like Us (1974)

April 25, 2016 4:24 PM - Subscribe

Two convicts break out of Mississippi State Penitentiary in 1936 to join a third on a long spree of bank robbing, their special talent and claim to fame. The youngest of the three falls in love along the way with a girl met at their hideout, the older man is a happy professional criminal with a romance of his own, the third is a fast lover and hard drinker fond of his work.

AV Club: Immediately defusing the highly charged nature of other movies about outlaws, Altman's gorgeous opening shot follows a handcart full of chain-gang members gliding down the tracks, then swings around to two men paddling a canoe in a pond. The men (Keith Carradine and John Schuck) are fugitives on the lam, but Altman's lyrical introduction sets a surprisingly gentle tone for the rest of the film to follow.

Slant: Altman lingers on the long, slow Southern days of these dim-witted bank robbers, and even though none of them are presented as very smart, witty, or smooth, the simple fact that we spend a great deal of time quietly observing them endears them to the viewer in a strange way. We may not even like them, but as they babble through philosophy or complain about their clothes or dream of having lots of money as the New Deal promises better days ahead, we feel like we understand them in some small way.

NYTimes: Society doesn't destroy these men. The Depression may have given them a push into their chosen professions, but they are, at heart, so self-destructive that I'm not at all sure they wouldn't have wound up much the same had they been farmers.

"Thieves Like Us" is not so perverse and witty as "The Long Goodbye," nor is it so ambitious as "McCabe and Mrs. Miller," but it is a more perfectly integrated work. It is full of things to think about, that hang in the memory like the details of a banal crime story on page 32, which, though read quickly, won't go away. Somehow you know that this happened.

Roger Ebert: The movie’s fault is that Altman, having found the perfect means for realizing his story visually, did not spend enough thought, perhaps, on the story itself. “Thieves Like Us” is not another “Bonnie and Clyde,” and yet it does end in a similar way, with a shoot-out. And by this time, we’ve seen too many movies that have borrowed that structure; that have counted on the bloody conclusion to lend significance to what went before. In “Thieves Like Us,” there just wasn’t that much significance, and I don’t think there’s meant to be. These are small people in a weary time, robbing banks because that’s their occupation, getting shot because that’s the law’s occupation.

Altman’s comment on the people and time is carried out through the way he observes them; if you try to understand his intention by analyzing the story, you won’t get far. Audiences have always been so plot-oriented that it’s possible they’ll just go ahead and think this is a bad movie, without pausing to reflect on its scene after scene of poignant observation. Altman may not tell a story better than any one, but he sees one with great clarity and tenderness.

Cineaste: Altman depicts their actions from a distance without any sentimentality and without ever making moral judgments or offering detailed psychological portraits. He also does not explain away their criminal behavior as a product of Depression-era poverty or as caused by the constricted nature of the small, bare Mississippi towns (looking a bit like Walker Evans photos) where the film takes place. The three bank robbers are viewed neither as victims of pernicious capitalism nor as social outlaws, but just as ordinary people who commit crimes and interact with other people who accept their actions with utter equanimity.

Trailer

AV Club: Immediately defusing the highly charged nature of other movies about outlaws, Altman's gorgeous opening shot follows a handcart full of chain-gang members gliding down the tracks, then swings around to two men paddling a canoe in a pond. The men (Keith Carradine and John Schuck) are fugitives on the lam, but Altman's lyrical introduction sets a surprisingly gentle tone for the rest of the film to follow.

Slant: Altman lingers on the long, slow Southern days of these dim-witted bank robbers, and even though none of them are presented as very smart, witty, or smooth, the simple fact that we spend a great deal of time quietly observing them endears them to the viewer in a strange way. We may not even like them, but as they babble through philosophy or complain about their clothes or dream of having lots of money as the New Deal promises better days ahead, we feel like we understand them in some small way.

NYTimes: Society doesn't destroy these men. The Depression may have given them a push into their chosen professions, but they are, at heart, so self-destructive that I'm not at all sure they wouldn't have wound up much the same had they been farmers.

"Thieves Like Us" is not so perverse and witty as "The Long Goodbye," nor is it so ambitious as "McCabe and Mrs. Miller," but it is a more perfectly integrated work. It is full of things to think about, that hang in the memory like the details of a banal crime story on page 32, which, though read quickly, won't go away. Somehow you know that this happened.

Roger Ebert: The movie’s fault is that Altman, having found the perfect means for realizing his story visually, did not spend enough thought, perhaps, on the story itself. “Thieves Like Us” is not another “Bonnie and Clyde,” and yet it does end in a similar way, with a shoot-out. And by this time, we’ve seen too many movies that have borrowed that structure; that have counted on the bloody conclusion to lend significance to what went before. In “Thieves Like Us,” there just wasn’t that much significance, and I don’t think there’s meant to be. These are small people in a weary time, robbing banks because that’s their occupation, getting shot because that’s the law’s occupation.

Altman’s comment on the people and time is carried out through the way he observes them; if you try to understand his intention by analyzing the story, you won’t get far. Audiences have always been so plot-oriented that it’s possible they’ll just go ahead and think this is a bad movie, without pausing to reflect on its scene after scene of poignant observation. Altman may not tell a story better than any one, but he sees one with great clarity and tenderness.

Cineaste: Altman depicts their actions from a distance without any sentimentality and without ever making moral judgments or offering detailed psychological portraits. He also does not explain away their criminal behavior as a product of Depression-era poverty or as caused by the constricted nature of the small, bare Mississippi towns (looking a bit like Walker Evans photos) where the film takes place. The three bank robbers are viewed neither as victims of pernicious capitalism nor as social outlaws, but just as ordinary people who commit crimes and interact with other people who accept their actions with utter equanimity.

Trailer

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by Slothrop at 4:16 AM on April 26, 2016