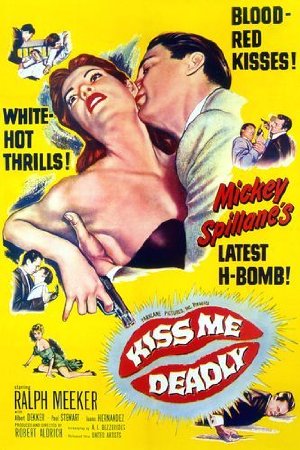

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

June 9, 2016 7:33 PM - Subscribe

A doomed female hitchhiker pulls Mike Hammer into a deadly whirlpool of intrigue, revolving around a mysterious "great whatsit."

Tor.com: The fact that producer-director Robert Aldrich’s 1955 Kiss Me Deadly is regarded as one of the classic films noir of the initial 1941-58 period is both self-evident it’s a great movie and a little odd, as it bears more in common with later movies, commonly called neo-noir, than it does most others of the classic period. Like those later movies, Kiss Me Deadly features all the hallmarks of noir because it is a film noir but it’s more, much more. It’s the first great hybrid between noir and SF.

Film Noir of the Week: Kiss Me Deadly really didn't resurface in the cinema consciousness until the early 1970s when the French term film noir broke into American film journals. It suddenly appeared in a pantheon of top titles that included Double Indemnity, The Big Sleep, Touch of Evil and Out of the Past. Previously ignored as an irrelevant addendum to Mickey Spillane's culturally abhorred world of tough guy pulp fiction, Robert Aldrich and screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides' film was heralded as an extreme expression of protest against 1950s conformist complacency. It subverted Spillane by criticizing his brutal avenger Mike Hammer as greedy, narcissistic and infantile.

A key talking point with Kiss Me Deadly was its unique apocalyptic ending. Bezzerides replaced the original novel's coveted drugs with a bizarre secret kept in a Pandora-like steel box. Hoping to sell the box to the highest bidder, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) tries to open it and is seared by a momentary blast of light and heat. Only afterwards is he told that the box is related to America's atomic energy program. The box is a door to the center of a nuclear reaction and, as indicated in the script's classical allusions, opening it will loose all of Pandora's evils into the world.

SFGate: Without giving anything away, the last shot shows two people walking into the ocean. In narrative terms the shot makes little sense, but on a symbolic, unconscious level nothing could be more appropriate. This picture, about a civilization on the edge of the apocalypse, ends with the bitter, haunting image of humanity returning to the slime.

Peter Bogdanovich: Kiss Me Deadly today seems remarkably modern. If only current pictures could be as well made, and as personal. The hardboiled script is by veteran shady-world scenarist A.I. Bezzerides, who wrote one of Jules Dassin’s most underrated movies, Thieves’ Highway (1949), and the excellent photography is by Ernest Laszlo, who conspires with Aldrich in the kind of angles that would have been unthinkable before Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1948). Clearly Aldrich had seen all the good movies. The ensemble cast includes edgy, unsentimental performances from numerous pros in this line of work, like Paul Stewart (a Welles alumni), Albert Dekker, Maxine Cooper, and Wesley Addy.

RogerEbert.com: There are so many masterful opening shots, some I find works of genius or some I simply love. But the more I thought about it, the more I drifted back to where my mind always manages to drift back to — stark, hard-boiled cruelty, paranoia, insanity and psycho sexual angst — so there it was again, “Kiss Me Deadly."

But for good reason. Robert Aldrich’s masterful noir hits you with a hysterical bang that sets its frenzied tone with such balls-out experimental élan; you can’t believe the film was released in 1955:

Before any credit sequence, the film begins with a pair of naked feet running down the middle of a highway in the black of the night.

The feet belong to a hysterical, heavily panting blonde (Cloris Leachman) wearing only a trench-coat. As the soundtrack intensifies, cars pass by but none stop. Desperate for a ride, she places herself in the middle of the road and stands holding her arms out in a V. Finally, a cool little Jaguar sports car comes to a screeching halt, blinding her with its headlights and swerving to the side of the road. She walks towards the car, roughly breathing and panting but with some relief. The driver, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) is agitated by this mystery woman/potential loony, begrudgingly “rescuing" her with a sneer. He spits:

“You almost wrecked my car. Well? Get in!"

As the woman enters the car, you hear a velvety-voiced female DJ announce a Nat King Cole song on the car radio. With the camera placed behind our two characters (one absolutely frantic, the other as cool as a cucumber), the credits roll upside down against the highway’s white lines. The only thing you hear is Nat King Cole’s elegant “Rather Have the Blues" and the woman’s hard, almost sexual sounding hyper-ventilating.

I’m still amazed by how totally perverse and subversive Aldrich’s kick start remains. How many pictures, even current pictures, would have the guts to place a viewer on this kind of edge? But he’s not playing simply for shock—Aldrich and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo instantly address the expressionistic, off kilter and monstrous universe we’re about to enter. Un-relenting, sleazy, mean, disorienting, neurotic, psychotic and hopeless, Leachman is the crazed conscious inside all of the film’s characters, maniacally running from a world that could explode (literally) by the opening of a suitcase. A seminal noir, a masterpiece of artistic pulp “Kiss Me Deadly" — opening shots alone — are exactly why the French praised Aldrich as “Le Gros Bob."

Slant: After Robert Aldrich brilliantly sets the table with this breakneck sequence, Mike reluctantly offers Christina a ride, fulfilling his manly duty in the “woman in distress” scenario without a hint of charm. During their short and fateful car ride, highlighted by the film's credits running in reverse, Mike proves he's a true bull and the world is his china shop, while Christina's fragility hints at an omniscient menace on the horizon. Mike's indifference slowly turns to intrigue as Christina becomes more cryptic, and her last words (“Remember me”) mark his subconscious for the remainder of the film. Mike is all instinct, and this opening tease sends his simple mind into a frenzied state.

AV Club: Kiss Me Deadly is unsentimental to the point of sadism. Director Robert Aldrich generally favors deep focus, but he can’t help but switch to a rare close-up to illustrate just how much our protagonist enjoys slamming a sleazy mortician’s hand in a drawer when he proves unhelpful. Hammer inhabits a world devoid of warm emotional attachments beyond his affection for his crudely stereotyped ethnic sidekick. Kiss Me Deadly begins tough, funny, and utterly original, a film noir for an age of nuclear paranoia. And it never lets up until a rightfully iconic ending (super-fan Quentin Tarantino borrowed elements of it wholesale for Pulp Fiction) that elevates proudly pulp subject matter to the level of savage pop art.

New Yorker DVD of the Week

Trailer

Full movie on YouTube

Tor.com: The fact that producer-director Robert Aldrich’s 1955 Kiss Me Deadly is regarded as one of the classic films noir of the initial 1941-58 period is both self-evident it’s a great movie and a little odd, as it bears more in common with later movies, commonly called neo-noir, than it does most others of the classic period. Like those later movies, Kiss Me Deadly features all the hallmarks of noir because it is a film noir but it’s more, much more. It’s the first great hybrid between noir and SF.

Film Noir of the Week: Kiss Me Deadly really didn't resurface in the cinema consciousness until the early 1970s when the French term film noir broke into American film journals. It suddenly appeared in a pantheon of top titles that included Double Indemnity, The Big Sleep, Touch of Evil and Out of the Past. Previously ignored as an irrelevant addendum to Mickey Spillane's culturally abhorred world of tough guy pulp fiction, Robert Aldrich and screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides' film was heralded as an extreme expression of protest against 1950s conformist complacency. It subverted Spillane by criticizing his brutal avenger Mike Hammer as greedy, narcissistic and infantile.

A key talking point with Kiss Me Deadly was its unique apocalyptic ending. Bezzerides replaced the original novel's coveted drugs with a bizarre secret kept in a Pandora-like steel box. Hoping to sell the box to the highest bidder, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) tries to open it and is seared by a momentary blast of light and heat. Only afterwards is he told that the box is related to America's atomic energy program. The box is a door to the center of a nuclear reaction and, as indicated in the script's classical allusions, opening it will loose all of Pandora's evils into the world.

SFGate: Without giving anything away, the last shot shows two people walking into the ocean. In narrative terms the shot makes little sense, but on a symbolic, unconscious level nothing could be more appropriate. This picture, about a civilization on the edge of the apocalypse, ends with the bitter, haunting image of humanity returning to the slime.

Peter Bogdanovich: Kiss Me Deadly today seems remarkably modern. If only current pictures could be as well made, and as personal. The hardboiled script is by veteran shady-world scenarist A.I. Bezzerides, who wrote one of Jules Dassin’s most underrated movies, Thieves’ Highway (1949), and the excellent photography is by Ernest Laszlo, who conspires with Aldrich in the kind of angles that would have been unthinkable before Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1948). Clearly Aldrich had seen all the good movies. The ensemble cast includes edgy, unsentimental performances from numerous pros in this line of work, like Paul Stewart (a Welles alumni), Albert Dekker, Maxine Cooper, and Wesley Addy.

RogerEbert.com: There are so many masterful opening shots, some I find works of genius or some I simply love. But the more I thought about it, the more I drifted back to where my mind always manages to drift back to — stark, hard-boiled cruelty, paranoia, insanity and psycho sexual angst — so there it was again, “Kiss Me Deadly."

But for good reason. Robert Aldrich’s masterful noir hits you with a hysterical bang that sets its frenzied tone with such balls-out experimental élan; you can’t believe the film was released in 1955:

Before any credit sequence, the film begins with a pair of naked feet running down the middle of a highway in the black of the night.

The feet belong to a hysterical, heavily panting blonde (Cloris Leachman) wearing only a trench-coat. As the soundtrack intensifies, cars pass by but none stop. Desperate for a ride, she places herself in the middle of the road and stands holding her arms out in a V. Finally, a cool little Jaguar sports car comes to a screeching halt, blinding her with its headlights and swerving to the side of the road. She walks towards the car, roughly breathing and panting but with some relief. The driver, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) is agitated by this mystery woman/potential loony, begrudgingly “rescuing" her with a sneer. He spits:

“You almost wrecked my car. Well? Get in!"

As the woman enters the car, you hear a velvety-voiced female DJ announce a Nat King Cole song on the car radio. With the camera placed behind our two characters (one absolutely frantic, the other as cool as a cucumber), the credits roll upside down against the highway’s white lines. The only thing you hear is Nat King Cole’s elegant “Rather Have the Blues" and the woman’s hard, almost sexual sounding hyper-ventilating.

I’m still amazed by how totally perverse and subversive Aldrich’s kick start remains. How many pictures, even current pictures, would have the guts to place a viewer on this kind of edge? But he’s not playing simply for shock—Aldrich and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo instantly address the expressionistic, off kilter and monstrous universe we’re about to enter. Un-relenting, sleazy, mean, disorienting, neurotic, psychotic and hopeless, Leachman is the crazed conscious inside all of the film’s characters, maniacally running from a world that could explode (literally) by the opening of a suitcase. A seminal noir, a masterpiece of artistic pulp “Kiss Me Deadly" — opening shots alone — are exactly why the French praised Aldrich as “Le Gros Bob."

Slant: After Robert Aldrich brilliantly sets the table with this breakneck sequence, Mike reluctantly offers Christina a ride, fulfilling his manly duty in the “woman in distress” scenario without a hint of charm. During their short and fateful car ride, highlighted by the film's credits running in reverse, Mike proves he's a true bull and the world is his china shop, while Christina's fragility hints at an omniscient menace on the horizon. Mike's indifference slowly turns to intrigue as Christina becomes more cryptic, and her last words (“Remember me”) mark his subconscious for the remainder of the film. Mike is all instinct, and this opening tease sends his simple mind into a frenzied state.

AV Club: Kiss Me Deadly is unsentimental to the point of sadism. Director Robert Aldrich generally favors deep focus, but he can’t help but switch to a rare close-up to illustrate just how much our protagonist enjoys slamming a sleazy mortician’s hand in a drawer when he proves unhelpful. Hammer inhabits a world devoid of warm emotional attachments beyond his affection for his crudely stereotyped ethnic sidekick. Kiss Me Deadly begins tough, funny, and utterly original, a film noir for an age of nuclear paranoia. And it never lets up until a rightfully iconic ending (super-fan Quentin Tarantino borrowed elements of it wholesale for Pulp Fiction) that elevates proudly pulp subject matter to the level of savage pop art.

New Yorker DVD of the Week

Trailer

Full movie on YouTube

Inspired to a rewatch by this post, I noticed how quickly and efficiently the film underscores the idea that Velda is the real detective. She tells Hammer that Ray Diker called while he was hospitalized, and has gathered a comprehensive file on him. When Hammer's frenemy on the force., Pat Murphy, shows up, Hammer reads from the file and Murphy remarks that Hammer "always did have a nose for information."

Throughout the film, Hammer and Soberin consistently reduce women to the level of animals, children, or objects. Hammer uses Velda as little more than a lure and quietly takes credit for her detective work; when he does talk to her, it's entirely for his own voyeuristic pleasure, as when he rejects sex with her and shortly afterwards expresses a greedy sexual pleasure in the blackmail tape she has made with the mark in one of their divorce-and-blackmail schemes. His interest in "Lily Carver" is linked very closely to the dead bird; when he first meets her, she holds up her arm like the broken wing of a bird, and Hammer will later "cage" her in his apartment while he looks for an angle to sell her out.

Meanwhile, Soberin compares Gabby/"Lily Carver" to a cat (and thus the predator that kills the bird) and contemptuously referring to the "creature comforts" she provided him; later he tells her the stories of Pandora, Lot's wife, and the Medusa. Even Pat Murphy and the authorities do the same, whether it's dehumanizing Cristina by holding her in an asylum and taking her clothes or scornfully treating Velda's endangerment as little more than an object lesson for Hammer once they have the key to the missing atomic device back.

But the women in film are equally consistent in retaining their agency. Velda, whose emotional and sexual abuse by Hammer is flagged up repeatedly across the film, is in the end the reason he survives and prior to that the reason he has any initial leads at all. And Gabrielle seizes the destructive power the men of the film seek after; it consumes her, of course, but only because she has played Hammer and Soberin to take possession of it. Cristina, for her part, escapes the asylum and takes the steps necessary to secure the Great Whatsis. Like Velda, she is a better detective than Hammer, summing him up with a quick scan of his car and covertly reading the registration on the steering column.

More subtly, there's Carl Evello's sister, a stereotype of a loose woman, but one who discomfits Hammer by owning her own sexuality and expressing her wish to possess him entirely. He rejects her, but the scenes that follow show that this means little to her; based on brief glimpses later on, she seems to be her brother's equal or at least his trusted advisor in their criminal enterprise. But unlike the "Bond girls" she superficially anticipates, Evello's sister is an incidental part of the narrative, and implicitly she survives it entirely unscathed...unlike her brother and his men.

Aldrich, Bezzerides, and their collaborators were way out in front of some things; beneath the film's exploitative surface is an interesting subversion of exploitation, part and parcel of the film's vicious satire of the original Spillane novels and the sort of society that made them so popular.

posted by kewb at 10:44 AM on June 12, 2016

Throughout the film, Hammer and Soberin consistently reduce women to the level of animals, children, or objects. Hammer uses Velda as little more than a lure and quietly takes credit for her detective work; when he does talk to her, it's entirely for his own voyeuristic pleasure, as when he rejects sex with her and shortly afterwards expresses a greedy sexual pleasure in the blackmail tape she has made with the mark in one of their divorce-and-blackmail schemes. His interest in "Lily Carver" is linked very closely to the dead bird; when he first meets her, she holds up her arm like the broken wing of a bird, and Hammer will later "cage" her in his apartment while he looks for an angle to sell her out.

Meanwhile, Soberin compares Gabby/"Lily Carver" to a cat (and thus the predator that kills the bird) and contemptuously referring to the "creature comforts" she provided him; later he tells her the stories of Pandora, Lot's wife, and the Medusa. Even Pat Murphy and the authorities do the same, whether it's dehumanizing Cristina by holding her in an asylum and taking her clothes or scornfully treating Velda's endangerment as little more than an object lesson for Hammer once they have the key to the missing atomic device back.

But the women in film are equally consistent in retaining their agency. Velda, whose emotional and sexual abuse by Hammer is flagged up repeatedly across the film, is in the end the reason he survives and prior to that the reason he has any initial leads at all. And Gabrielle seizes the destructive power the men of the film seek after; it consumes her, of course, but only because she has played Hammer and Soberin to take possession of it. Cristina, for her part, escapes the asylum and takes the steps necessary to secure the Great Whatsis. Like Velda, she is a better detective than Hammer, summing him up with a quick scan of his car and covertly reading the registration on the steering column.

More subtly, there's Carl Evello's sister, a stereotype of a loose woman, but one who discomfits Hammer by owning her own sexuality and expressing her wish to possess him entirely. He rejects her, but the scenes that follow show that this means little to her; based on brief glimpses later on, she seems to be her brother's equal or at least his trusted advisor in their criminal enterprise. But unlike the "Bond girls" she superficially anticipates, Evello's sister is an incidental part of the narrative, and implicitly she survives it entirely unscathed...unlike her brother and his men.

Aldrich, Bezzerides, and their collaborators were way out in front of some things; beneath the film's exploitative surface is an interesting subversion of exploitation, part and parcel of the film's vicious satire of the original Spillane novels and the sort of society that made them so popular.

posted by kewb at 10:44 AM on June 12, 2016

Saw this recently. If this film had ended 20 minutes earlier it would have been one of the most amazing film endings I've ever seen.

Consider: Mike Hammer has been your stereotypical tough-guy film noir hero throughout - half-con, half-brute, not above beating people up or sleeping with them or lying to them in the pursuit of the information he needs. He scoffs at the warnings from the police and the FBI that he shouldn't get involved.

And then he finds out what the "Great Whatsit" is everyone is looking for, and does something I've never seen a noir detective do before - he gets scared. He goes to the police chief and tells him everything, and the chief reads him the riot act, telling him that of course he knew what this was all about, that was why he warned Hammer not to get involved, but Hammer had to go ahead and meddle anyway and that just made everything worse. He starts storming out, leaving Hammer there, looking chastened and terrified, and protesting "but....but I didn't know...."

That to me felt like a sort of meta-acknowledgement of the Cold War and how it had changed everything. The old tough-guy stuff didn't work any more - the stakes were way higher and way more complicated. The time of the old-school noir detective was over. And for me, that scene acknowledged that.

I wish to God that this had ended there.

posted by EmpressCallipygos at 11:42 AM on September 2, 2020 [1 favorite]

Consider: Mike Hammer has been your stereotypical tough-guy film noir hero throughout - half-con, half-brute, not above beating people up or sleeping with them or lying to them in the pursuit of the information he needs. He scoffs at the warnings from the police and the FBI that he shouldn't get involved.

And then he finds out what the "Great Whatsit" is everyone is looking for, and does something I've never seen a noir detective do before - he gets scared. He goes to the police chief and tells him everything, and the chief reads him the riot act, telling him that of course he knew what this was all about, that was why he warned Hammer not to get involved, but Hammer had to go ahead and meddle anyway and that just made everything worse. He starts storming out, leaving Hammer there, looking chastened and terrified, and protesting "but....but I didn't know...."

That to me felt like a sort of meta-acknowledgement of the Cold War and how it had changed everything. The old tough-guy stuff didn't work any more - the stakes were way higher and way more complicated. The time of the old-school noir detective was over. And for me, that scene acknowledged that.

I wish to God that this had ended there.

posted by EmpressCallipygos at 11:42 AM on September 2, 2020 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

The film really is an indictment of a whole culture, a remarkably vicious and thorough one. Hammer is a narcissist and a sadist, but he's shown to be a comparatively small and stupid one. He plays little games with divorce-case clients and with Velda. But the sorts of peopler he ends up dealing with are playign the same games on a global scale; Hammer smashes people's hands, smashes Caruso records, smashes everything in his path to get what he wants. But his opponents are people who smash atoms and countries, who have weapons of intimidation and destruction beyond Hammer's most self-indulgent fantasies.

It's a film aboiut superficial, childish, masculine power fantasies, usually wrapped up as modernity and sophistication: Hammer's souped-up car and his ultra-modern apartment; Dr. Soberin's useless classical education and high diction; and Carl Evello's world-weary posing.

But it's the people cut out of or victimized by this swaggering, stupid barbarism who actually know things and accomplish things in the film. Velda unravels more of the mystery than Hammer ever does; Lily Carver is more than a match for Soberin and Hammer; and Christina devastatingly sums up Hammer within the first few minutes of the film: But Hammer is too sure of himself, his toughness, and his "instincts" to notice what he needs to. So is Soberin. And, the film implies, so too are the people who made the Great Whatsit. The world of the film ultimately belongs to the marginalized, the victimized, the survivors. It is not a pretty world, but it is theirs if it can endure.

posted by kewb at 1:13 PM on June 10, 2016 [1 favorite]