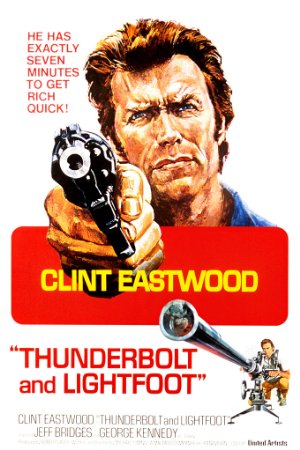

Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

April 11, 2016 6:57 PM - Subscribe

With the help of an irreverent young sidekick, a bank robber gets his old gang back together to organize a daring new heist.

NYTimes: Mr. Eastwood is a smart fellow. For his Malpaso Company unit, he engaged a bright new young director, Michael Cimino, who also wrote an original script that is freshly turned in characterization and plot, amusingly ribald and neatly paced. The pattern is essentially familiar—crime still doesn't pay and the big climactic heist misfires—but Mr. Cimino's expert piloting scoots the action forward colorfully. The playing is entirely disarming, with Mr. Eastwood's wry restraint meshing perfectly with Mr. Bridges's impish exuberance, and Geoffrey Lewis and George Kennedy lending sturdy support.

As Frank Stanley's beautiful photography evokes the sweep of Montana's Big Sky country, the picture mercifully avoids footnotes on social significance except for one subtle, succinct touch in a climactic, schoolhouse scene, a thoughtful twist. The Eastwood team has pulled off a modest enjoyable winner.

The Guardian: Inspired by Captain Lightfoot, a 1955 Douglas Sirk picture about 19th-century Irish highwaymen, it's a knowing, fast-moving combination of road movie and heist thriller, a bromance as we'd now call it, with homoerotic and homophobic undertones. It's set entirely in the beautiful, thinly populated "big sky country" of Idaho and Montana. On the soundtrack there's twanging country music by Dee Barton, who wrote the score for Eastwood's Play Misty for Me and High Plains Drifter.

The Dissolve: The 1974 directorial debut of Michael Cimino packs a lot of of subtext into what could have been a standard caper film, albeit one whose final, headlong descent into grimness marked it as a product of its pessimistic era. But even before the film’s finale, it’s filled with nods to changing times and the traumatic effects of recent American history, themes Cimino explored on an operatic scale in his next film, The Deer Hunter. Here, when Thunderbolt And Lightfoot’s heroes arrive at a plaque noting, “The one-room schoolhouse evokes a vision of a vanished America” outside a building that’s been preserved as a landmark, the film doesn’t dwell on the significance, but doesn’t look away from it, either. If America ever had room for the film’s free-spirited criminals, not villains so much as men determined to live outside society’s confines, it doesn’t have room for them now.

denofgeek: Like many great road movies of the time, Thunderbolt And Lightfoot combines character study with a topographical glance at the American national psyche, though not quite to the same scathing level as some of its contemporaries.

Slant: The film's pairing of old and young functions not as a commentary on the generation gap or the trading of an antiquated set of values for a newer one, but as a means of drawing out their parallels. Certainly Thunderbolt (Clint Eastwood) and Lightfoot (Jeff Bridges) are introduced as contrasts: black-clad Thunderbolt hunched over the pulpit of a church, the sunlight glinting off his glasses further obscuring him, while Lightfoot, decked out in bright, post-hippie patterns and pleats, practically materializes just outside the dealership where he jacks a car. Once thrown together, however, their rapport becomes a juxtaposition of different personalities voicing the same core being. Bridges brings his off-kilter sense of humor to his role, while Eastwood remains more taciturn, but both characters are sardonic, shrewd robbers, desirous of a payday for the same reason, to finally be able to just buy something of their own. It's a dream so myopic, so survivalist, that it transcends an identifiable political slant even as it epitomizes the microeconomic impact of politics on the poor across generations.

Trailer

NYTimes: Mr. Eastwood is a smart fellow. For his Malpaso Company unit, he engaged a bright new young director, Michael Cimino, who also wrote an original script that is freshly turned in characterization and plot, amusingly ribald and neatly paced. The pattern is essentially familiar—crime still doesn't pay and the big climactic heist misfires—but Mr. Cimino's expert piloting scoots the action forward colorfully. The playing is entirely disarming, with Mr. Eastwood's wry restraint meshing perfectly with Mr. Bridges's impish exuberance, and Geoffrey Lewis and George Kennedy lending sturdy support.

As Frank Stanley's beautiful photography evokes the sweep of Montana's Big Sky country, the picture mercifully avoids footnotes on social significance except for one subtle, succinct touch in a climactic, schoolhouse scene, a thoughtful twist. The Eastwood team has pulled off a modest enjoyable winner.

The Guardian: Inspired by Captain Lightfoot, a 1955 Douglas Sirk picture about 19th-century Irish highwaymen, it's a knowing, fast-moving combination of road movie and heist thriller, a bromance as we'd now call it, with homoerotic and homophobic undertones. It's set entirely in the beautiful, thinly populated "big sky country" of Idaho and Montana. On the soundtrack there's twanging country music by Dee Barton, who wrote the score for Eastwood's Play Misty for Me and High Plains Drifter.

The Dissolve: The 1974 directorial debut of Michael Cimino packs a lot of of subtext into what could have been a standard caper film, albeit one whose final, headlong descent into grimness marked it as a product of its pessimistic era. But even before the film’s finale, it’s filled with nods to changing times and the traumatic effects of recent American history, themes Cimino explored on an operatic scale in his next film, The Deer Hunter. Here, when Thunderbolt And Lightfoot’s heroes arrive at a plaque noting, “The one-room schoolhouse evokes a vision of a vanished America” outside a building that’s been preserved as a landmark, the film doesn’t dwell on the significance, but doesn’t look away from it, either. If America ever had room for the film’s free-spirited criminals, not villains so much as men determined to live outside society’s confines, it doesn’t have room for them now.

denofgeek: Like many great road movies of the time, Thunderbolt And Lightfoot combines character study with a topographical glance at the American national psyche, though not quite to the same scathing level as some of its contemporaries.

Slant: The film's pairing of old and young functions not as a commentary on the generation gap or the trading of an antiquated set of values for a newer one, but as a means of drawing out their parallels. Certainly Thunderbolt (Clint Eastwood) and Lightfoot (Jeff Bridges) are introduced as contrasts: black-clad Thunderbolt hunched over the pulpit of a church, the sunlight glinting off his glasses further obscuring him, while Lightfoot, decked out in bright, post-hippie patterns and pleats, practically materializes just outside the dealership where he jacks a car. Once thrown together, however, their rapport becomes a juxtaposition of different personalities voicing the same core being. Bridges brings his off-kilter sense of humor to his role, while Eastwood remains more taciturn, but both characters are sardonic, shrewd robbers, desirous of a payday for the same reason, to finally be able to just buy something of their own. It's a dream so myopic, so survivalist, that it transcends an identifiable political slant even as it epitomizes the microeconomic impact of politics on the poor across generations.

Trailer

A good movie if you want to see a variety of cars going around doing stuff you don't usually see. Also a tiny bit of gun porn; the importance of the big autocannon is overstated. And really just good for actor-watching.

It also seems like a decent example of what I think of as a 70s worship of the free individual, glorifying the unrestrained id. Well, at least there's not a lot of tedious drugs and alcohol stuff to endure in this movie. Though sometimes I think that what I don't see in this kind of rebellion movie is what is being rebelled against. No doubt the feeling of pervasive, restrictive social norms was stronger then, but the feeling of like complete moral confusion and reactionary hedonism feel less relevant.

Sorry this is the dumb shit I think about when I watch 70s movies.

Also very 70s is the reaching beyond racism while at the same time being sexist as hell. Though I laughed when Lightfoot tried to horndog up on the woman on the motorcycle and she got out a hammer and smacked his truck over and over. Also strange to imagine the hootin' and hollerin' that Beau Bridge's cross-dressing might have caused. They were horny, horny times.

There's a sort of critical view of these movies, any kind of movie that takes place west of the Mississippi perhaps, or especially road movies, that feel very fake to me. They purport to be about mythical America, or at least the mythical West, but they don't feel like real myths to me, they feel like literary or critical or Hollywood myths. Easy Rider can unsubtly juxtapose a farrier shoeing a horse and a guy repairing a motorcycle, but that's a fake connection between what went on in that movie and like, ranch work. My feelings for No Country kind of mix with this, and I just feel like taking this whole criticism-generated genre of like the meta-post-Western, the mythologizing the myth of the West itself.. I just wanna wad it up and throw it away.

posted by fleacircus at 1:42 AM on May 27, 2019

It also seems like a decent example of what I think of as a 70s worship of the free individual, glorifying the unrestrained id. Well, at least there's not a lot of tedious drugs and alcohol stuff to endure in this movie. Though sometimes I think that what I don't see in this kind of rebellion movie is what is being rebelled against. No doubt the feeling of pervasive, restrictive social norms was stronger then, but the feeling of like complete moral confusion and reactionary hedonism feel less relevant.

Sorry this is the dumb shit I think about when I watch 70s movies.

Also very 70s is the reaching beyond racism while at the same time being sexist as hell. Though I laughed when Lightfoot tried to horndog up on the woman on the motorcycle and she got out a hammer and smacked his truck over and over. Also strange to imagine the hootin' and hollerin' that Beau Bridge's cross-dressing might have caused. They were horny, horny times.

There's a sort of critical view of these movies, any kind of movie that takes place west of the Mississippi perhaps, or especially road movies, that feel very fake to me. They purport to be about mythical America, or at least the mythical West, but they don't feel like real myths to me, they feel like literary or critical or Hollywood myths. Easy Rider can unsubtly juxtapose a farrier shoeing a horse and a guy repairing a motorcycle, but that's a fake connection between what went on in that movie and like, ranch work. My feelings for No Country kind of mix with this, and I just feel like taking this whole criticism-generated genre of like the meta-post-Western, the mythologizing the myth of the West itself.. I just wanna wad it up and throw it away.

posted by fleacircus at 1:42 AM on May 27, 2019

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by davidmsc at 9:19 AM on April 12, 2016