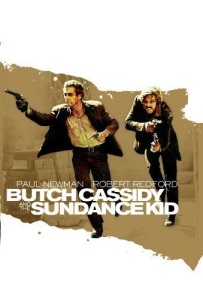

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

June 9, 2018 3:58 PM - Subscribe

Wyoming, early 1900s. Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid are the leaders of a band of outlaws. After a train robbery goes wrong they find themselves on the run with a posse hard on their heels. Their solution - escape to Bolivia.

Roger Ebert: The movie starts promisingly, with an amusing period-piece newsreel about the Cassidy gang. And then there is a scene in a tavern where Sundance faces down a tough gambler, and that's good. And then a scene where Butch puts down a rebellion in his gang, and that's one of the best things in the movie. And then an extended bout of train-robbing, climaxing in a dynamite explosion that'll have you rolling in the aisles. And then we meet Sundance's girlfriend, played by Katharine Ross, and the scenes with the three of them have you thinking you've wandered into a really first-rate film.

But the trouble starts after Harriman hires his posse. It's called the Super-posse because it includes all the best lawmen and trackers in the West. When it approaches, the ground rumbles and we get the feeling it's a supernatural force. Butch and the Kid try to hide in the badlands, but the Super-posse cannot be fooled. It's always on their track. Forever.

Director George Roy Hill apparently spent a lot of money to take his company on location for these scenes, and I guess when he got back to Hollywood he couldn't bear to edit them out of the final version. So the Super-posse chases our heroes unceasingly, until we've long since forgotten how well the movie started and are desperately wondering if they'll ever get finished riding up and down those endless hills. And once bogged down, the movie never recovers.

It does show moments of promise, however, after Butch, the Kid and his girl go to Bolivia. There are some funny difficulties with Spanish, for example. But here the script throws us off. Goldman has his heroes saying such quick, witty and contemporary things that we're distracted: it's as if, in 1910, they were consciously speaking for the benefit of us clever 1969 types.

This dialog is especially inappropriate in the final shoot-out, when it gets so bad we can't believe a word anyone says. And then the violent, bloody ending is also a mistake; apparently it was a misguided attempt to copy "Bonnie and Clyde." But the ending doesn't belong on "Butch Cassidy," and we don't believe it, and we walk out of the theater wondering what happened to that great movie we were seeing until an hour ago.

Pauline Kael: All this is, in a way, part of the background of why, after a few minutes of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, I began to get that depressed feeling, and, after a half hour, felt rather offended. We all know how the industry men think: they’re going to try to make “now” movies when now is already then, they’re going to give us orgy movies and plush skinflicks, and they’ll be trying to feed youth’s paranoia when youth will, one hopes, have cast it off like last year’s beads. This Western is a spinoff from Bonnie and Clyde; it’s about two badmen (Paul Newman and Robert Redford) at the turn of the century, and the script, by William Goldman, which has been published, has the prefatory note “Not that it matters, but most of what follows is true.” Yet everything that follows rings false, as that note does.

It’s a facetious Western, and everybody in it talks comical. The director, George Roy Hill, doesn’t have the style for it. (He doesn’t really seem to have the style for anything, yet there is a basic decency and intelligence in his work.) The tone becomes embarrassing. Maybe we re supposed to be charmed when this affable, loquacious outlaw Butch and his silent, “dangerous” buddy Sundance blow up trains, but how are we supposed to feel when they go off to Bolivia, sneer at the country, and start shooting up poor Bolivians? George Roy Hill is a “sincere” director, but Goldman’s script is jocose; though it reads as if it might play, it doesn’t, and probably this isn’t just Hill’s fault. What can one do with dialogue like Paul Newman’s Butch saying, “Boy, I got vision. The rest of the world wears bifocals”? It must be meant to be sportive, because it isn’t witty and it isn’t dramatic. The dialogue is all banter, all throwaways, and that’s how it’s delivered; each line comes out of nowhere, coyly, in a murmur, in the dead sound of the studio. (There is scarcely even an effort to supply plausible outdoor resonances or to use sound to evoke a sense of place.) It’s impossible to tell whose consciousness the characters are supposed to have.

The Hollywood Reporter: For an industry whose portion of non-creative, irresponsible agents and system-bound producers have brought it close to collapse by over-pricing familiar failures whose liability to endless productions is the only clear measurable, it is a relatively promising event to encounter a screenplay which has been overpriced in direct ratio to its merit. 20th's release of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a Campanile production, has both William Goldman's justly expensive screenplay and two stars who could not be better fitted to the realization of the title roles. Thus inspired, director George Roy Hill's intelligence and craft have never been so clearly and confidently manifest in bringing to the screen the aggregate virtues of the ingredients.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the story of two of the most likeable outlaws in western history, researched in facts and conveyed in joyous contemporary spirit, employing the broadcast spectrum of creative techniques to sustain the timeless aura of legend and the vital, damned-fool heroics of its characters. Both are still young, yet nearly over the hill, threatened by the increasingly dirty, mechanized resource of law-men and the railroads, who are taking the sport and the wits out of the chase. A Newman-Foreman presentation, produced by John Foreman, with Paul Monash as executive producer, the picture stars Paul Newman, Robert Redford and Katharine Ross. In no less degree, it stars cinematographer Conrad Hall. It is a great film and will be an exceptionally popular and profitable one.

Variety: Novelty is inserted in an interlude sequence as the two outlaws and Katharine Ross, the Kid’s woman, pause in New York en route to sailing for South America. This is shown through a series of fast amusing oldtime stills of the period a la daguerreo-types as the trio is limited in various poses in Gotham, Coney Island, etc. Effective use is made of music in this sequence to give a lilting lightness to the whole idea.

Newman and Redford both sock over their respective roles with a humanness seldom attached to outlaw characters and Miss Ross, who shares star billing, is excellent as the understanding girl friend who refuses to remain with them in Bolivia to see them killed. George Furth, too, has an amusing brief bit as the agent on the express car who defies Butch during two different holdups.

Empire: Coming as it did at the end of Hollywood's love affair with the romantic notion of the West, and on the cusp of its later dissection of the Western archetype, Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid avoids falling between these two stools; instead it finds the Western, like its central characters, in transition. Hell, it's kept William Goldman in work for over three decades, even though he's only written a handful of decent screenplays since. Year Of The Comet, anyone?

There are, of course, the points against: Newman's bike riding to B. J. Thomas redefines the word 'twee', and George Roy Hill could be held singlehandedly responsible for begetting what we now perceive as the 'buddy movie' (with the director and his star re-teaming for The Sting a mere four years later), and its influence can still be felt today in everything from the Lethal Weapon franchise, to Thelma And Louise and beyond.

But along the way Butch and Sundance take the time to provide us with cinema's greatest waterfall leap (and how many Sunday afternoons have been defined by Redford yelling "Shiiiiitttt!!!!" - in a family film, no less?), and one of cinema's most memorable and elegiac endings, as Butch and Sundance literally fade into a photo memory. In fact, it's hard to imagine that a movie with the Burt Bacharach career low of 'Raindrops keep falling on my head/And just like the guy whose feet are too big for his bed' could ever feel this good.

AV Club: Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid might not have invented the modern buddy comedy, but it may as well have. While Lethal Weapon screenwriter Shane Black was still toddling around playing cowboys and Indians, director George Roy Hill, cinematographer Conrad Hall, composer Burt Bacharach, stars Paul Newman and Robert Redford, and screenwriter William Goldman were meticulously crafting the gold standard for movies about rugged pals quipping and wisecracking their way through one perilous bonding situation after another. Goldman has criticized his Oscar-winning screenplay for being overly clever, which is akin to job applicants who cite their biggest flaws as "I'm too hard-working" or "I'm too much of a perfectionist." But Goldman has a point. Butch Cassidy's dialogue is so unrelentingly sarcastic and irreverent that the film sometimes feels like an especially sharp Mad Magazine parody of itself. In one of the special features included in the two-disc special edition, Hill is reported to have complained following a screening that people were laughing at his tragedy. But tragedies are seldom this glib. Then again, they're seldom this fun or consistently entertaining, either.

In performances that cemented their iconic status, Newman and Redford star as two of the Old West's best-looking and quickest-witted outlaws, genial gentlemen bandits who flee to South America rather than face a "super-posse" representing a railroad baron the duo repeatedly robbed. Newman and Redford try to outrun their past, but their enemies aren't about to let them off easy.

Though Hall's stunning vistas and gorgeous exploration of wide-open spaces hearken back to John Ford, Butch Cassidy otherwise radiates the youthful energy, manic pop playfulness, and antic clowning of the French New Wave. The film's subversive attitude toward genres and genre-mashing echoes the pioneering work of Jean-Luc Godard, and Newman and Redford deliver an extended master class on the uses of old-school, twinkly-eyed movie-star charisma. Though the encroachment of the modern world in the form of super-posses, vengeful tycoons, and the taming of the once-wild West spell doom for the film's loveable anti-heroes, that smartass, incorrigible modernity is precisely what ensures Butch Cassidy's timelessness.

Trailer

Art of the Title

Filming Locations

‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ is a true western epic passionately remembered decades upon its initial release

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid isn't the glib buddy comedy we remember

Roger Ebert: The movie starts promisingly, with an amusing period-piece newsreel about the Cassidy gang. And then there is a scene in a tavern where Sundance faces down a tough gambler, and that's good. And then a scene where Butch puts down a rebellion in his gang, and that's one of the best things in the movie. And then an extended bout of train-robbing, climaxing in a dynamite explosion that'll have you rolling in the aisles. And then we meet Sundance's girlfriend, played by Katharine Ross, and the scenes with the three of them have you thinking you've wandered into a really first-rate film.

But the trouble starts after Harriman hires his posse. It's called the Super-posse because it includes all the best lawmen and trackers in the West. When it approaches, the ground rumbles and we get the feeling it's a supernatural force. Butch and the Kid try to hide in the badlands, but the Super-posse cannot be fooled. It's always on their track. Forever.

Director George Roy Hill apparently spent a lot of money to take his company on location for these scenes, and I guess when he got back to Hollywood he couldn't bear to edit them out of the final version. So the Super-posse chases our heroes unceasingly, until we've long since forgotten how well the movie started and are desperately wondering if they'll ever get finished riding up and down those endless hills. And once bogged down, the movie never recovers.

It does show moments of promise, however, after Butch, the Kid and his girl go to Bolivia. There are some funny difficulties with Spanish, for example. But here the script throws us off. Goldman has his heroes saying such quick, witty and contemporary things that we're distracted: it's as if, in 1910, they were consciously speaking for the benefit of us clever 1969 types.

This dialog is especially inappropriate in the final shoot-out, when it gets so bad we can't believe a word anyone says. And then the violent, bloody ending is also a mistake; apparently it was a misguided attempt to copy "Bonnie and Clyde." But the ending doesn't belong on "Butch Cassidy," and we don't believe it, and we walk out of the theater wondering what happened to that great movie we were seeing until an hour ago.

Pauline Kael: All this is, in a way, part of the background of why, after a few minutes of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, I began to get that depressed feeling, and, after a half hour, felt rather offended. We all know how the industry men think: they’re going to try to make “now” movies when now is already then, they’re going to give us orgy movies and plush skinflicks, and they’ll be trying to feed youth’s paranoia when youth will, one hopes, have cast it off like last year’s beads. This Western is a spinoff from Bonnie and Clyde; it’s about two badmen (Paul Newman and Robert Redford) at the turn of the century, and the script, by William Goldman, which has been published, has the prefatory note “Not that it matters, but most of what follows is true.” Yet everything that follows rings false, as that note does.

It’s a facetious Western, and everybody in it talks comical. The director, George Roy Hill, doesn’t have the style for it. (He doesn’t really seem to have the style for anything, yet there is a basic decency and intelligence in his work.) The tone becomes embarrassing. Maybe we re supposed to be charmed when this affable, loquacious outlaw Butch and his silent, “dangerous” buddy Sundance blow up trains, but how are we supposed to feel when they go off to Bolivia, sneer at the country, and start shooting up poor Bolivians? George Roy Hill is a “sincere” director, but Goldman’s script is jocose; though it reads as if it might play, it doesn’t, and probably this isn’t just Hill’s fault. What can one do with dialogue like Paul Newman’s Butch saying, “Boy, I got vision. The rest of the world wears bifocals”? It must be meant to be sportive, because it isn’t witty and it isn’t dramatic. The dialogue is all banter, all throwaways, and that’s how it’s delivered; each line comes out of nowhere, coyly, in a murmur, in the dead sound of the studio. (There is scarcely even an effort to supply plausible outdoor resonances or to use sound to evoke a sense of place.) It’s impossible to tell whose consciousness the characters are supposed to have.

The Hollywood Reporter: For an industry whose portion of non-creative, irresponsible agents and system-bound producers have brought it close to collapse by over-pricing familiar failures whose liability to endless productions is the only clear measurable, it is a relatively promising event to encounter a screenplay which has been overpriced in direct ratio to its merit. 20th's release of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a Campanile production, has both William Goldman's justly expensive screenplay and two stars who could not be better fitted to the realization of the title roles. Thus inspired, director George Roy Hill's intelligence and craft have never been so clearly and confidently manifest in bringing to the screen the aggregate virtues of the ingredients.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the story of two of the most likeable outlaws in western history, researched in facts and conveyed in joyous contemporary spirit, employing the broadcast spectrum of creative techniques to sustain the timeless aura of legend and the vital, damned-fool heroics of its characters. Both are still young, yet nearly over the hill, threatened by the increasingly dirty, mechanized resource of law-men and the railroads, who are taking the sport and the wits out of the chase. A Newman-Foreman presentation, produced by John Foreman, with Paul Monash as executive producer, the picture stars Paul Newman, Robert Redford and Katharine Ross. In no less degree, it stars cinematographer Conrad Hall. It is a great film and will be an exceptionally popular and profitable one.

Variety: Novelty is inserted in an interlude sequence as the two outlaws and Katharine Ross, the Kid’s woman, pause in New York en route to sailing for South America. This is shown through a series of fast amusing oldtime stills of the period a la daguerreo-types as the trio is limited in various poses in Gotham, Coney Island, etc. Effective use is made of music in this sequence to give a lilting lightness to the whole idea.

Newman and Redford both sock over their respective roles with a humanness seldom attached to outlaw characters and Miss Ross, who shares star billing, is excellent as the understanding girl friend who refuses to remain with them in Bolivia to see them killed. George Furth, too, has an amusing brief bit as the agent on the express car who defies Butch during two different holdups.

Empire: Coming as it did at the end of Hollywood's love affair with the romantic notion of the West, and on the cusp of its later dissection of the Western archetype, Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid avoids falling between these two stools; instead it finds the Western, like its central characters, in transition. Hell, it's kept William Goldman in work for over three decades, even though he's only written a handful of decent screenplays since. Year Of The Comet, anyone?

There are, of course, the points against: Newman's bike riding to B. J. Thomas redefines the word 'twee', and George Roy Hill could be held singlehandedly responsible for begetting what we now perceive as the 'buddy movie' (with the director and his star re-teaming for The Sting a mere four years later), and its influence can still be felt today in everything from the Lethal Weapon franchise, to Thelma And Louise and beyond.

But along the way Butch and Sundance take the time to provide us with cinema's greatest waterfall leap (and how many Sunday afternoons have been defined by Redford yelling "Shiiiiitttt!!!!" - in a family film, no less?), and one of cinema's most memorable and elegiac endings, as Butch and Sundance literally fade into a photo memory. In fact, it's hard to imagine that a movie with the Burt Bacharach career low of 'Raindrops keep falling on my head/And just like the guy whose feet are too big for his bed' could ever feel this good.

AV Club: Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid might not have invented the modern buddy comedy, but it may as well have. While Lethal Weapon screenwriter Shane Black was still toddling around playing cowboys and Indians, director George Roy Hill, cinematographer Conrad Hall, composer Burt Bacharach, stars Paul Newman and Robert Redford, and screenwriter William Goldman were meticulously crafting the gold standard for movies about rugged pals quipping and wisecracking their way through one perilous bonding situation after another. Goldman has criticized his Oscar-winning screenplay for being overly clever, which is akin to job applicants who cite their biggest flaws as "I'm too hard-working" or "I'm too much of a perfectionist." But Goldman has a point. Butch Cassidy's dialogue is so unrelentingly sarcastic and irreverent that the film sometimes feels like an especially sharp Mad Magazine parody of itself. In one of the special features included in the two-disc special edition, Hill is reported to have complained following a screening that people were laughing at his tragedy. But tragedies are seldom this glib. Then again, they're seldom this fun or consistently entertaining, either.

In performances that cemented their iconic status, Newman and Redford star as two of the Old West's best-looking and quickest-witted outlaws, genial gentlemen bandits who flee to South America rather than face a "super-posse" representing a railroad baron the duo repeatedly robbed. Newman and Redford try to outrun their past, but their enemies aren't about to let them off easy.

Though Hall's stunning vistas and gorgeous exploration of wide-open spaces hearken back to John Ford, Butch Cassidy otherwise radiates the youthful energy, manic pop playfulness, and antic clowning of the French New Wave. The film's subversive attitude toward genres and genre-mashing echoes the pioneering work of Jean-Luc Godard, and Newman and Redford deliver an extended master class on the uses of old-school, twinkly-eyed movie-star charisma. Though the encroachment of the modern world in the form of super-posses, vengeful tycoons, and the taming of the once-wild West spell doom for the film's loveable anti-heroes, that smartass, incorrigible modernity is precisely what ensures Butch Cassidy's timelessness.

Trailer

Art of the Title

Filming Locations

‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ is a true western epic passionately remembered decades upon its initial release

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid isn't the glib buddy comedy we remember

I’m with Ebert. The first half (or so) is great. The last half is barely OK, and the ending is just bad.

However, and even though it’s in the worse half, “the fall’s gonna kill ya” is one of my favorite lines of dialog, ever.

posted by Frayed Knot at 5:10 PM on June 9, 2018 [2 favorites]

However, and even though it’s in the worse half, “the fall’s gonna kill ya” is one of my favorite lines of dialog, ever.

posted by Frayed Knot at 5:10 PM on June 9, 2018 [2 favorites]

Butch: "Somebody say '1, 2, 3, go.'"

Sundance: "123go."

posted by kirkaracha at 1:50 PM on June 10, 2018

Sundance: "123go."

posted by kirkaracha at 1:50 PM on June 10, 2018

Hell, it's kept William Goldman in work for over three decades, even though he's only written a handful of decent screenplays since. Year Of The Comet, anyone?

Marathon Man, anyone? All the President's Men, anyone? A Bridge Too Far, anyone? The Princess Bride, anyone? A Few Good Men, anyone? Chaplin, anyone? Misery, anyone?

posted by kirkaracha at 1:54 PM on June 10, 2018 [5 favorites]

Marathon Man, anyone? All the President's Men, anyone? A Bridge Too Far, anyone? The Princess Bride, anyone? A Few Good Men, anyone? Chaplin, anyone? Misery, anyone?

posted by kirkaracha at 1:54 PM on June 10, 2018 [5 favorites]

it's as if, in 1910, they were consciously speaking for the benefit of us clever 1969 types.

It is strange to think we are almost as far from the release of the movie as it was from the events it (roughly) depicts.

I can see how one could dislike the glibness but it is hard to deny the effect it had on Hollywood. No Butch and Sundance leads to no Luke and Han, no Murtaugh and Riggs, no Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, no Blues Brothers, maybe no Withnail and I, no Wayne and Garth, and Owen Wilson being just the guy who played the unsettling killer in The Minus Man.

Me, I love it, (give or take the inexplicable three-minute Burt Bacharach video).

posted by ricochet biscuit at 2:26 PM on June 17, 2018 [1 favorite]

It is strange to think we are almost as far from the release of the movie as it was from the events it (roughly) depicts.

I can see how one could dislike the glibness but it is hard to deny the effect it had on Hollywood. No Butch and Sundance leads to no Luke and Han, no Murtaugh and Riggs, no Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, no Blues Brothers, maybe no Withnail and I, no Wayne and Garth, and Owen Wilson being just the guy who played the unsettling killer in The Minus Man.

Me, I love it, (give or take the inexplicable three-minute Burt Bacharach video).

posted by ricochet biscuit at 2:26 PM on June 17, 2018 [1 favorite]

You are not logged in, either login or create an account to post comments

posted by sammyo at 4:37 PM on June 9, 2018